The ultimate rockabilly cult figure, Charlie Feathers cut classics like Tongue-Tied Jill and Bottle To The Baby but recognition was not easy to come by…

Max Décharné in his A Rocket In My Pocket: The Hipster’s Guide To Rockabilly allocates an entire chapter to Charlie Feathers. Only Elvis Presley gets a similar amount of space. The section also features some of the most impassioned writing in the book, Décharné correctly taking to task Greil Marcus for the absurdly dismissive statement in his Mystery Train book that “Charlie Feathers [was] a country singer of no special talent or even much drive.”

Many other people believe Feathers is the embodiment of rockabilly. It’s not just the classic, slightly unsettling sound of his music that entitles him to that status. It’s also for his maverick tendencies, the fact that he was a working class, poorly educated guy who refused to toe the line or compromise his values. His total lack of commercial success means that he can be seen as a kind of heroic loser.

Music Maverick

But Feathers was also a chippy character, and his voice was an acquired taste. He told tall stories that exaggerated his importance in the development of the Sun sound, yet the few records he made while there are disappointing. Feathers claimed that Buddy Holly learnt his hiccupping style from him. If he did, he was certainly learning from the best. But while Holly had a voice that has reached out to youth across the ages, Feathers was always quirky, appealing only to a clued-up minority prepared to run with his eccentricity.

Aside from on bootlegs, his music was practically unheard of in Europe until it started being released in licensed form in the 70s. By the end of the decade, he was crossing the Atlantic to play, accompanied by his son Bubba on guitar, but his gigs could be a bit of a lottery, with too much chatting between songs.

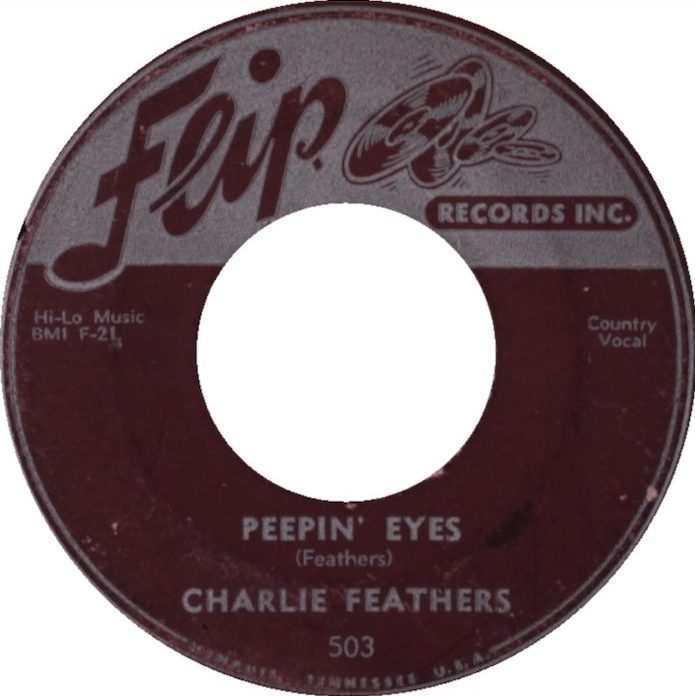

Yet few artists talked more interestingly about what rockabilly was and how it should be done. Like Carl Perkins, Feathers claimed he was doing rockabilly before Elvis teamed up with Scotty Moore and Bill Black in Memphis. To Charlie, rockabilly was cotton patch blues hitched on the back of bluegrass and upped in pace and energy. He maintained Elvis’ version of Bill Monroe’s Blue Moon Of Kentucky was learnt from his own demo of the song. It’s an unsubstantiated claim, but not so unbelievable given Feathers’ love of bluegrass, and the way Monroe’s high and lonesome sound can be heard in Charlie’s voice on tracks such as Peepin’ Eyes.

The Drums Don’t Work

It was Feathers who staunchly maintained that rockabilly is best when played by a trio consisting of a vocalist, usually playing rhythm guitar, backed by a lead guitar and a string bass, with no drummer. One of the weirdest albums Feathers ever did was a one-off for Elektra in 1991, on which he was accompanied by the ex-Sun sidemen Roland Janes (electric guitar), Stan Kesler (bass, steel guitar) and J.M. Van Eaton (drums).

Featuring his eccentric take on 14 of his own and other people’s songs, it’s not the best entry point to the world of Feathers and unlikely to appeal to any but his diehards, but the sleevenotes contain some interesting quotes from an interview with Feathers by Ben Sandmel.

Feathers told Sandmel that “drums don’t really work with rockabilly. They collide with the bass. It ain’t really rockabilly if you use drums. That just turns it into rock.” He then adds the rider that “drums are OK on rockabilly if it’s a running lick, like Buddy Holly’s Peggy Sue – that’s rockabilly when you keep that flow going.”

Authentic Rockabilly

Feathers didn’t have much to say about his own vocal style, but if you were writing a textbook on how to sing authentic rockabilly he’d be a prime example. At a gig in England, performing One Hand Loose, Feathers could be heard telling the hired backing band to lower their volume, thereby actually increasing the power of the song.

It’s noticeable that Feathers, like many of the 50s rockabillies, never really shouts on his recordings. But few brought such variety to the rockabilly vocal style. In support of his distinctive Southern twang, among the effects he deployed were growls, stutters, hiccups, squawks, squeals, sobs, whoops, yelps and hollers. He sometimes used a cat-like mewing sound, or an eerie, almost canine howl. Even stranger was when he bought his delivery down to speak lines in a swampy, sinister, bass voice.

Canine Howl

Yet however nonsensical were the words or noises he emitted, he always managed to sound sincere and heartfelt. Perhaps that was why Sam Phillips thought he would have been better off sticking to country and could have been as big as George Jones. That would have deprived us of many great songs, however.

Because of Phillips’ view, the most interesting recordings that Feathers made were not courtesy of Sun. Born into a sharecropping family in Myrtle, near Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1932, he had worked on oil pipelines in Illinois and Texas before arriving in Memphis in 1950. Around about 1954 he was a regular at the studio singing in the style of Hank Williams. When Phillips launched the Flip label in 1955 to highlight the country side of artists on his roster, Feathers was a natural fit for it.

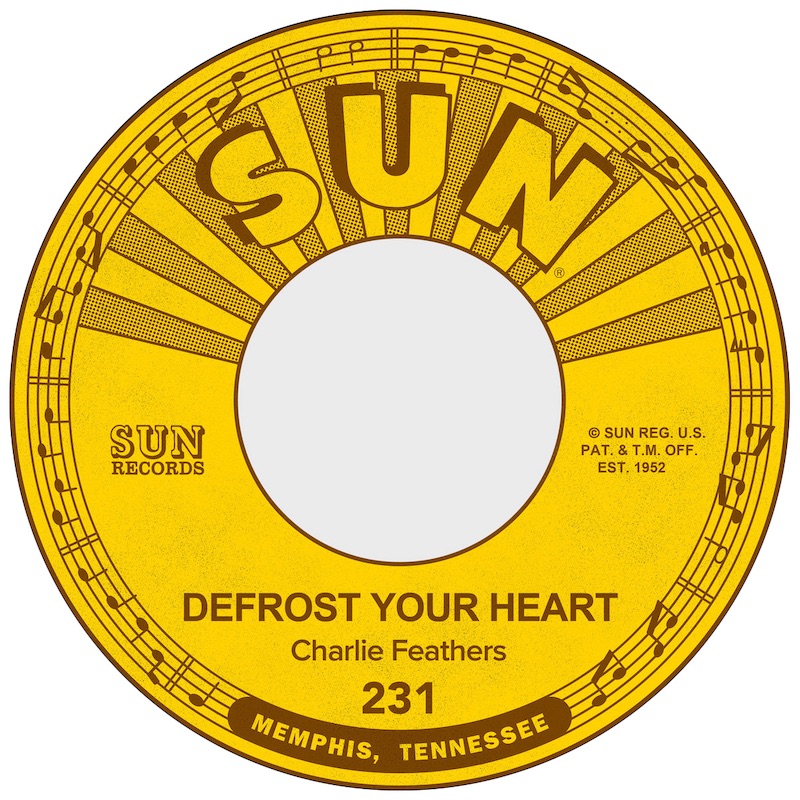

However, the singles I’ve Been Deceived b/w Peepin’ Eyes, and Defrost Your Heart paired with A Wedding Gown Of White – the latter released on Sun after Flip was forced to close – are not really the reasons we listen to Feathers now.

Escape Route

Phillips recognised the blues feeling that Feathers was able to inject into country songs, but he didn’t rate him as a rocker. In any case, Charlie was difficult to work with. A solid rockabilly version of Corrine, Corrina, an old folk standard that Joe Turner had success with transforming into an R&B classic, was the best of his Sun work, but Phillips didn’t release it.

There was an escape route, though. Les Bihari, co-founder with his brothers of the West Coast-based Modern Records, had set up the Meteor label in Memphis to establish a presence in the South. Bihari succeeded in attracting several Sun artists disenchanted by Phillips’ neglect of their output thanks to his successive concentration of promoting Presley, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis. Among the Sun alumni who recorded for the label were Malcolm Yelvington, under the alias Mac Sales, Rufus Thomas, Little Milton and Jess Hooper.

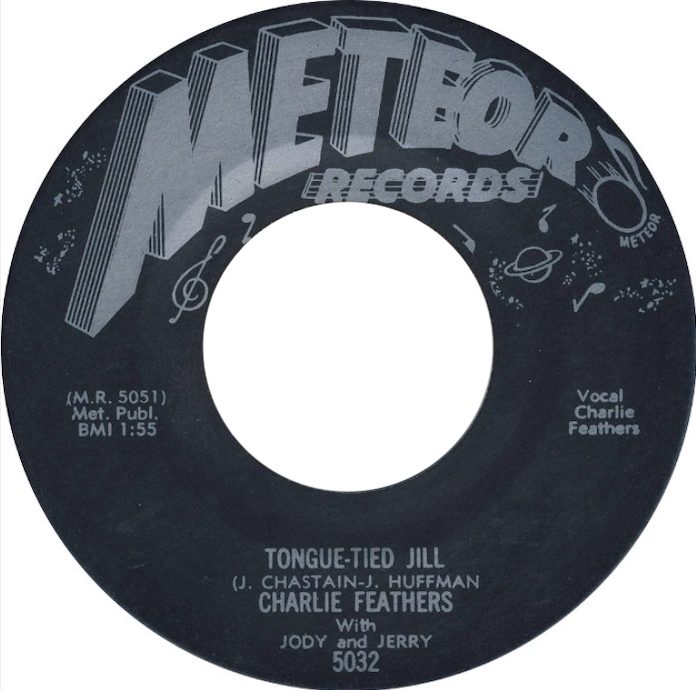

Feathers was courted by Bihari, too, and it was for Meteor that he recorded two songs that most perfectly epitomised his ideas about the performance of rockabilly. Strictly adhering to the drummerless trio format, Tongue-Tied Jill / Get With It, was released as a single in 1956. On Get With It Feathers sets out the musical template, singing, “Well you pick the tune, and you slap the bass/ I’ll play the rhythm and I’ll set the pace/ But we gotta get with it, no time to waste!” Both songs exude rhythmic drive, power and an off-kilter sense of excitement without assaulting the eardrums. Feathers’ wordless, stuttering conclusion to Tongue-Tied Jill can be viewed as one of the definitive moments in rockabilly singing.

Jungle Fever

On the back of the Meteor release came an offer for the trio to record for Syd Nathan’s King Records in Cincinnati. More good but largely ignored material emerged. One Hand Loose, on which Feathers’ recently acquired drummer Jimmy Swords played, and Can’t Hardly Stand It, which was a rare example of a slow-paced rockabilly song but which still featured the singer’s distinctive hiccupping, emerged as a single taken from the first session. This was followed by another essential single Bottle To The Baby, of which Feathers had recorded an earlier and unreleased version at Sun.

For the small Memphis independent Kay, Feathers recorded the slapback-heavy Jungle Fever b/w Why Don’t You in 1958. Label-hopping was to be his destiny over the following years, while taking on work outside the music business. By the mid-1960s he was scraping a living driving in stock car races. It was the fabled Welsh Teddy boy “Breathless” Dan Coffey, on one of his record collecting trips to the States, who tracked Feathers down and got him back into the studio to record for the first time in years in 1968. Stutterin’ Cindy showed all the quirky mannerisms were intact. Within 10 years he’d be appearing in London, fittingly given the accolades he’d always considered his by right.

For more Charlie Feathers at Sun Records click here

Read More: When rockabilly shook the world