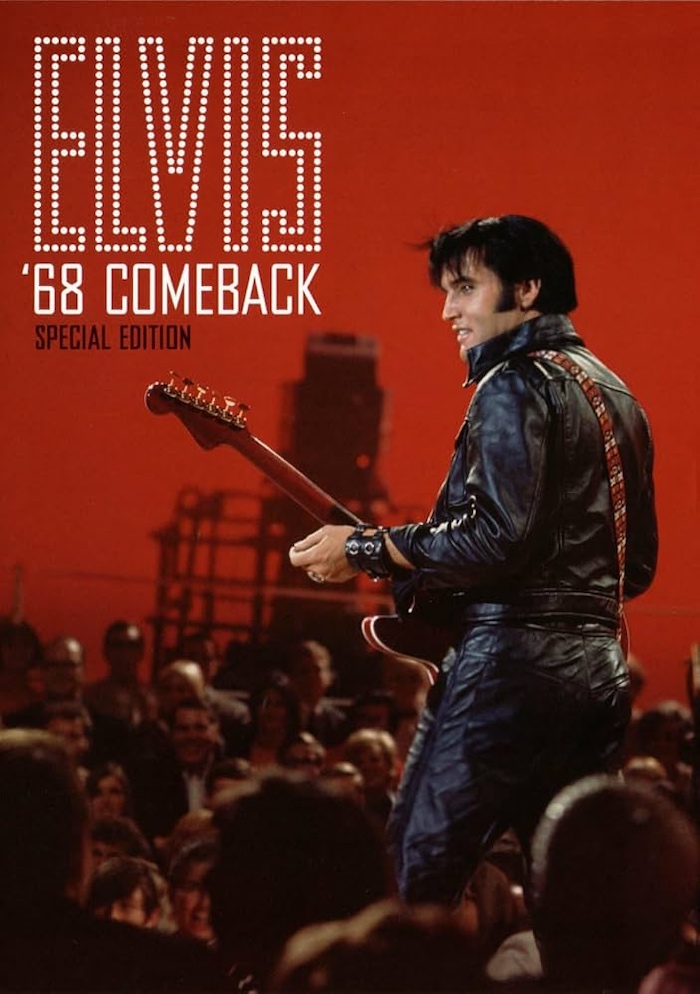

Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special was a vital turning point in the life of The King of Rock’n’Roll. It re-energised his career, reformed his image for a new generation and set him back on course as a hitmaker and serious artist. Vintage Rock traces the history of a seminal moment in Presley’s resurgence – Words by Randy Fox

The year 1968 was a brutal one for the United States. In April, Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, and the event sparked racial riots across the country. Two months later, presidential candidate Robert F Kennedy was also assassinated. The war in Vietnam escalated while opposition grew, as many Americans questioned the validity of a seemingly senseless conflict. During the Democratic National Convention, anti-war protesters clashed with police, leading to massive arrests. A contentious Presidential race resulted in the election of Richard Nixon, a polarising figure who hardened the already existing divisions in the country.

And then, on 3 December 1968, more than 42 million Americans tuned their TV sets to the NBC Television Network, united in the glow of cathode-ray tubes to witness the return of Elvis Presley. Longtime faithful fans, former admirers whose loyalties had moved on to newer music, a young generation of music fans who only knew Elvis as the star of ridiculous and cornball movies, sceptical older viewers curious about the hype – all of them waited to see what the King would do in his first TV Special.

Sexy & Dangerous

As the NBC network ID faded from TV screens, Elvis’ face appeared. Looking sexy and dangerous, he sang the opening lines of the Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller song, Trouble.

“If you’re lookin’ for trouble,”

“You came to the right place.”

“If you’re lookin’ for trouble,”

“Just look right in my face…”

As the camera pulled back, Elvis was revealed against pitch-black darkness, dressed all in black with a red silk scarf around his neck and a cherry-red electric guitar strapped over his shoulder. He belted out the blues into the microphone he gripped tightly in his hand. There was little doubt, the King of rock’n’roll had returned – and nothing would be the same again.

By 1968, Elvis Presley was well aware that he needed a change. Only 10 years had passed since his induction into the US Army had dominated headlines and thousands of teenagers swarmed train stations to say farewell to the King of rock’n’roll. Upon his return to civilian life in 1960, he recorded Elvis Is Back, one of the best albums of his career, made a handful of live appearances and closed the deal on a record-setting multi-picture movie contract that seemed to guarantee both continued stardom and an extraordinarily healthy bank account. But the feeling of victory was fleeting.

As the 1960s ground on, Elvis’ movies became more routine and ridiculous. He became a prisoner of his own success and a joke to a new generation of rock’n’roll fans. Of the two elements of showbusiness he enjoyed most – freewheeling recording sessions and performing live – the first happened less and less, and the second had ground to a complete halt.

A Cool Million

Although Elvis’ films in the early 60s were box-office smashes, by 1967, they were barely making it into the black. Both MGM and Paramount had little interest in new contracts, especially at the payscale that Elvis’ manager, Colonel Tom Parker, demanded. With the fortunes of his sole client sinking, the Colonel decided to take a different approach to Hollywood. In late 1967, he proposed a deal with the NBC Television Network. NBC could have exclusive rights to a 1968 Christmas special if it could persuade a movie studio to partner with it for a one-picture deal. The price tag was $1.25 million, which would deliver a cool million for Elvis after the Colonel’s commission was deducted.

NBC took the bait, and brought its frequent business partner, Universal Studios, into the deal. NBC supplied slightly more than $400,000 and Universal Studios supplied the rest of the price tag. The Colonel was ecstatic. While Elvis clearly appreciated the million-dollar payoff, the prospect of making yet another inane movie was not thrilling, nor was the idea of singing Christmas songs to television cameras.

Elvis’ attitude soon changed, however. In the spring of 1968, Bob Finkel was chosen by NBC to produce the television Special. His first order of business was to convince the Colonel, NBC and the programme’s sponsor, the Singer Sewing Machine Company, that the show needed to focus solely on Elvis and his music rather than be a by-the-numbers Christmas special. Finkel was an experienced and successful producer, with two Emmy awards for his work on The Andy Williams Show. Finkel soon won the battle for creative control; next, he had to convince his star.

Movie Monotony

In May 1968, Finkel met with Elvis several times to explain his ideas. At first, Elvis seemed disinterested. Gradually, he became enthusiastic as Finkel gained his trust and the star began to see the Special as a way to break free of the box that eight years of movies had placed around him.

With Elvis committed to the TV show, Finkel began gathering his production team. For director, he chose Steve Binder, a 35-year-old up-and-coming film and television director who directed the rock TV show Hullabaloo for NBC and the popular concert film The T.A.M.I. Show, which featured James Brown, The Rolling Stones, The Beach Boys and more. Binder’s business partner and audio engineer, Bones Howe, was another professional with a top-notch reputation, and came with the added bonus of previously working with Elvis in 1956 and 1957 at Radio Recorders studios in Hollywood.

With the creative team in place, they began working on the concept for the show. The show would be built around the Jerry Reed song, Guitar Man, a No.43 hit for Elvis just a few months earlier. The song, a travelogue of the eponymous guitar man’s adventures, served as a linking theme connecting segments featuring Elvis in concert before a live studio audience, an informal jam session, and choreographed production numbers. The plan to present Elvis in a new light extended to the wardrobe design. Steve Binder was adamant that Elvis should avoid the flashy, Hollywood showbiz look or sharp-cut suits seen in most TV variety specials. Costume designer Bill Belew’s masterpiece was a soft, flexible black leather suit with a stand-up collar framing Elvis’ face. It was simple, cool and the total opposite of the flash and tinsel so often associated with Hollywood TV programmes.

The Real Elvis

Throughout the first weeks of June, the production team refined the script and Elvis worked hard rehearsing, learning to hit his marks on the complex dance numbers and working on arrangements with musical director William Goldenberg. Each night, Elvis would unwind in his dressing room – joking, laughing and singing songs in jam sessions with his friend Charlie Hodge and other members of his entourage.

One night, director Steve Binder wandered in on the festivities and was struck with the idea of throwing out the plans for the Special and simply shooting an entire programme in the dressing room, cinéma vérité style. This was the real Elvis, and a side of him which had never been seen by the public.

Although Binder soon returned to the original, more conventional format, he changed the plans for the Special in one very important way. The script for the informal jam session was thrown out and instead, Binder gave Elvis a list of suggested topics to talk about. After further talks with Elvis, Binder also decided to fly in guitarist Scotty Moore and drummer DJ Fontana from Memphis for the ‘sit-down’ show.

On 20 June, Elvis arrived at Western Recorders Studios for four days of recording sessions. All the music for the production numbers was pre-recorded. Elvis would later perform his vocals live during the taping. However, for some shots, recording live vocals would not be practical.

Home For Christmas

To solve this problem, Elvis pre-recorded vocals on an isolated vocal track for removal or insertion as needed. Knowing that Elvis preferred recording with a live band, rather than simply overdubbing vocal tracks in the studio, Bones Howe had Elvis record his vocals in an isolation booth with a glass window, so he could watch the musicians as they played. Howes also gave him a hand microphone to use, to make the experience more like that of playing a live performance.

While the sessions proceeded, Steve Binder searched for a satisfying finale. The plan was to end with a simple performance of I’ll Be Home For Christmas, a compromise with the Colonel after Bob Finkel steered the show away from a Christmas theme. Binder hated the compromised ending and began thinking about the integrated nature of the show – different races working together toward a common goal.

With that idea in mind, he approached the show’s vocal arranger, Earl Brown, and asked him to compose a big show closer on the theme of racial harmony. The next morning, Brown had the finished song in hand. If I Can Dream was a simplistic plea for a better world, but the type of soaring, dramatic song that Elvis could make his own. Binder, Brown and Howe managed to corral Elvis in a dressing room, away from the Colonel, and Brown played the song for him while Binder gave the sales pitch. After hearing the song six times, Elvis was sold, and with 100 per cent of the copyright for the song assigned to Elvis’ publishing company, the Colonel went along with the change.

Gripped By Stagefright

With the music for the production numbers completed, final preparations were made for shooting the concert segments and sit-down show. Moore and Fontana flew in five days before shooting began and immediately fell into the groove with Elvis, reminiscing about old times and adventures.

Excited but also nervous about the special, Elvis explained it was the key for reviving his career and returning to live performances. With the addition of Elvis’ friends Charlie Hodge, Alan Fortas and Lance LeGault, the small group gathered in Elvis’ dressing room for dry runs on the sit-down portion of the show on the evenings of 24 and 25 June.

The morning of 27 June, shooting began with a couple of the production numbers for the Special’s carnival midway sequence. With those completed, Elvis took the afternoon off to prepare for his first live show in front of an audience in over seven years.

They planned to shoot two versions of the sit-down show, one at 6pm and another at 8pm. Two shows would provide more options for the final cut. With a small audience of around 200 seated in the NBC Studio and another 50 or so (mostly younger women) seated on the steps leading up to the small ‘boxing ring’ stage, the show was ready to begin.

Backstage, Elvis was in the grip of an overwhelming bout of stage fright. As Binder later recalled to writer Peter Guralnick, Elvis was in a panicked state. What if he froze up? What if he couldn’t think of anything to say? Binder’s reply was straightforward: “Then you go out, sit down, look at everyone, get up, and walk off,” he said. “But you are going out there.”

Up Close And Personal

Binder’s admonition worked. Elvis walked out, took the stage and greeted the audience. Although he was plainly nervous, he thanked the audience, cracked a few jokes and introduced Scotty and DJ, while skipping over the other members of his onstage entourage. With that out of the way, he launched into That’s All Right, with a short but enthusiastic greeting of applause from the audience.

In a matter of seconds, the transformation was astounding. With the camera close on Elvis’s face, one could see him retreating into the music through the first lines of the opening chorus, and then, sure enough, the rockabilly livewire who first thrilled audiences 12 years earlier came bursting forth.

The sense of excitement grows throughout the performance as he twists in his seat, falls deeper into the music and jokes with his bandmates. Like a cat tensing right before the attack, Elvis seemed to be on the edge of breaking loose throughout the hour-long set. Three songs in, he traded guitars with Scotty Moore, and then continued to play the electric guitar throughout the show. Swept away by the excitement, he tried standing several times, but the cramped arrangement on the small stage seemed to prevent him from doing so.

Finally, on the penultimate number, One Night, he could no longer contain himself and moved his chair back just enough to stand, delivering a charged performance of the classic rhythm ’n’ blues tune. Then, almost as an afterthought, he moved to the opposite edge of the stage, and – sitting between two adoring young ladies – brought the show to a tearjerking close with the ballad, Memories.

A Dream Return

There was no doubt it was a spectacular and special performance, and a vindication of all the concepts that Finkel, Binder and Howe had infused into the Special. After a shower for the star, a fast cleaning for Elvis’ black leather suit, and a slight rearrangement of the audience, Elvis came back to perform again.

For the second show, his confidence was plainly evident from the moment he walked on stage, and the resulting show was looser and more freewheeling than the first.

The next day was spent shooting the gospel-medley production number and the bordello scene showcasing the song Let Yourself Go. After the success of the previous night’s show, Elvis was in top form. Unfortunately, the bordello sequence was cut from the Special after the show’s sponsor, the Singer Sewing Machine Company, feared it might offend some viewers.

On 29 June, a live audience again filled the NBC studio for two performances of the ‘stand-up show’. A live band was used for most of the show, while pre-recorded backing tracks were utilised for the rest. As with the sit-down show, Elvis displayed some jitters as he came out on stage for the first performance, but they quickly evaporated as he wowed the crowd. At the end of the second show, drenched in sweat, he called the Colonel to his dressing room. As soon as he arrived, Elvis had a direct order for him. He wanted to start touring again.

The next day was spent on final takes and reshoots for the production numbers. Although Howe had some reservations about the live sound, due to NBC’s antiquated sound system, Finkel and Binder knew they had captured something truly special. It wasn’t just an entertaining show: they had captured the magic of Elvis’ rebirth as an artist.

A New Hope

While the post-production team assembled the final cut for NBC, Elvis found himself back in the same old grind that had ruled his life for many years. He spent several weeks in July shooting the film Charro. Although Elvis initially had high hopes for the picture, changes to the script watered down what was supposed to be a gritty western and a hoped-for change of pace from his other movies. In October, he began work on yet another film, The Trouble With Girls, the final picture of his MGM contract. This time, there wasn’t even a pretence of change from the usual formula.

Despite these frustrations, Elvis found new hope in the idea that a major change was coming soon, hinging on the TV Special. With the air-date approaching, the Colonel’s promotion machine kicked into high gear. A single of the Special’s closing song, If I Can Dream, was released on 5 November and rose steadily up the charts. It would eventually reach No. 12 on Billboard’s Hot 100, making it the biggest-selling Elvis single since 1965.

Finally, on Tuesday 3 December 1968, American TV screens were filled with 90 minutes of a man reclaiming his musical soul. Celebrity TV Specials were the common currency of the day and everyone thought they knew what to expect – overblown production numbers, corny comedy skits, bundles of celebrity guest stars and inane patter. Not only was Elvis (the official name of the TV Special) breaking the mould, it was revelling in its rebellion. More than 42 million Americans tuned in, making it the highest-rated show of the 1968 to 1969 television season. The news spread quickly; if you had missed Elvis on TV, you had missed something truly special.

Bouncing Back

Although not every critic was impressed — the Los Angeles Times, in an astonishing display of cluelessness, snarked: “I don’t think many viewers care to see singers sweat on TV” – Elvis fans, both veterans and the newly won over, loved it. The soundtrack album from the special, released by RCA Victor 11 days before the special aired, took off in sales, rising to No. 8 on the Billboard Album Chart, making it the highest charting Elvis LP in over three years.

The Colonel wasted no time in capitalising on the success of the Special. Within weeks, he closed a deal for Elvis to appear at the newly-built International Hotel in Las Vegas for a four-week engagement. Just seven weeks after the Special, Elvis began recording at American Studios in Memphis, cutting new material that not only reinvented his sound for a new era, but also garnered major hits. Although he appeared in one more film (see boxout on page 9), the movie era of Elvis’ career had forever ended and a new road as a live performer and recording artist lay before him.

Never before in TV history had anyone witnessed such a dramatic and radical reinvention of career and image. Music journalist Jon Landau perhaps said it best when he wrote about the Special in Eye Magazine: “There is something magical in watching a man who has lost himself find his way home again.”

To buy Elvis click here

Out Now: Vintage Rock Presents Elvis The Early Years