The Great Rock’n’Roll Revival of the late 60s through the early 70s, saw the original rock’n’rollers return with a mix of nostalgia shows and bold new recordings. High points included Wembley Stadium’s first mega-gig and a revival of rockin’ 50s culture across TV and movies. But why did it happen?

These days, revival acts, nostalgia tours and reliving days gone by make up one of music’s biggest scenes, with the hits of the past having a bright future. But it wasn’t always so. Pop culture is expected to keep moving, changing… and it did. Until the great rock’n’roll revival of the late 60s and early 70s, when, for many, the clock was turned back.

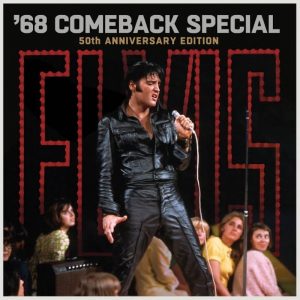

There was probably no single reason the wave of nostalgia spiked so dramatically, but there was a tide on the rise. In 1968, Elvis had returned to wild acclaim with his ‘Comeback Special’; the deified Beatles were putting out retro tunes (Back In The U.S.S.R., Lady Madonna) even as they splintered; and forgotten man Fats Domino issued the acclaimed Fats Is Back album, cannily covering Lady Madonna, a song he had inspired. Fats Is Back was an important LP: it didn’t dump the essence of Domino’s sound but smartly updated it.

Show ’Em How It’s Done

It proved the originals could still deliver without compromise. A marker was laid down in, of all places, Canada. The Toronto Rock’n’Roll Revival show of September 1969 optimistically mixed 50s titans – Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Bo Diddley and Jerry Lee Lewis – with hip acts such as The Doors, Chicago Transit Authority and nascent shock-rocker Alice Cooper. But it made big headlines, mainly because John Lennon and his new Plastic Ono Band gave what was the star’s first live appearance without his Fab-mates. Lennon had been invited as compère, but it wasn’t clear if he would perform. His set has become known (via the album release) as Live Peace In Toronto 1969, but Toronto was intended, really, as simply a rock’n’roll show.

South East in NYC, US promoter/radio man Richard Nader had grown up on the early rockers and was convinced there was a dedicated ‘oldies’ market just waiting to be tapped. Nader had spent a few years promoting The Who, The Animals, Herman’s Hermits and other UK groups in the US, and was irked that the American heroes of his youth had been swept aside by these British Invasion bands.

The Comeback Begins

In October 1969, Nader presented the first of his many rock’n’roll revivals at New York’s vast Madison Square Garden. Unlike the pick and mix line-up in Toronto, this was more focused nostalgia and starred Berry, The Platters and – performing in the US for the first time in a decade – Bill Haley and his Comets. Amid the prevailing ‘counter culture’ of freakouts, druggy experimentalism and psychedelic funk, this was a brave call indeed.

To many people’s surprise, including the acts involved, it was a massive success. “They [the artists] didn’t think the public wanted to see them anymore,” Nader later told journalist Gary James. “The Coasters’ manager didn’t believe I was gonna pull the show off , so he booked The Coasters elsewhere. Bill [Haley] was living in Mexico at the time. I spent hours over a period of months trying to convince him to come up and do the show. He hemmed and hawed. So I begged him, did whatever I had to do to get him.”

Nader’s drive was admirable and unwavering. He’d had to borrow the start-up money from an office furniture manufacturer in order to put on his first show, and Bill Haley wasn’t the only star that he had to coax out of retirement. For one of his later 25 gigs at the Garden, Nader was determined to get Bo Diddley onto the bill, only to find out that the guitar slinger was by this time working in a restaurant attached to a garage because his car had broken down and he couldn’t afford to get it repaired…

Retro-Rocking Quality

But before long, the shows had moved from MSG’s Felt Forum to the Garden’s 20,000-capacity Main Arena and – like a throwback to the days of Alan Freed – Nader’s name was writ large on the posters as a guarantee of retro-rocking quality.

Within a few years, old was the new new, and some UK artists were also looking back: in 1970, Dave Edmunds charted with an unlikely cover of Smiley Lewis’s I Hear You Knocking from 1955, and Shakin’ Stevens And The Sunsets cut the album A Legend. Produced by fellow Welshman Edmunds, it didn’t sell too many, but they built a solid following in mainland Europe.

The Sunsets’ manager Paul Barrett was so impressed when reading of Lennon’s appearance at the revival show in Toronto, he promptly wrote a letter to the music press inviting him to audition for The Sunsets. Of course, it didn’t work, but Barrett’s chutzpah impressed the Rolling Stones so much they gave Shaky and the band a support slot.

The Rill Thing

Outside of the A&R offices of London, New York and LA, where the latest pop fad was chased like a rabbit, there was clearly still an appetite for the music of ‘yesterday’. After all, it had only been a decade since rock’n’roll ruled, so why should it now be written off as moribund?

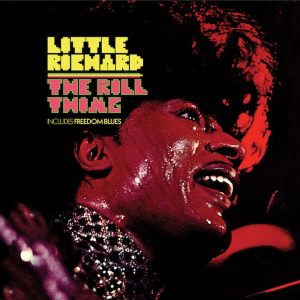

Back in the USA, some record companies were wise to it. Reprise Records signed Little Richard in 1970 and he released the album, The Rill Thing, with the 7″ Freedom Blues becoming his biggest single in years. He even made the cover of Rolling Stone magazine, which would have been unimaginable two years earlier.

In 1971, disc jockey Jerry Osborne started an ‘oldies’ format on FM radio in Phoenix, Arizona, and it was so successful that others quickly emulated it across the States. In Chicago, a new musical by Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey debuted, revisiting its authors’ high school life: they called it Grease, after the greasers of the 50s. Within a year, it was playing on Broadway. The revival was hitting the big time… and it was coming across the water.

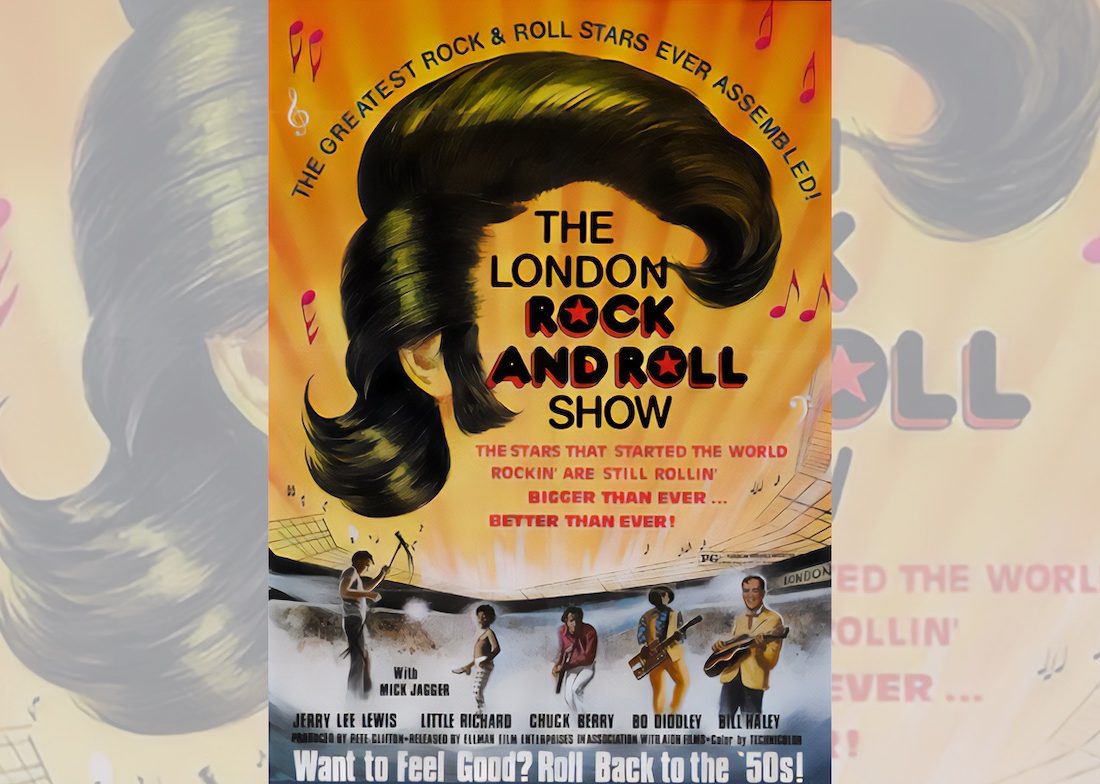

The London Rock And Roll Show

It was no surprise that a retro show had the potential to be huge in the UK. The original rock’n’roll pioneers did play the UK in the 50s, sure, but only to a switched-on smaller audience and rarely together. Even so, the London Rock and Roll Show of 1972 was a milestone event: it was the first time Wembley Stadium had been booked for a dedicated music gig.

Bar Elvis deciding to finally visit England, the line-up was as strong as any 50s rocker could realistically hope for: Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bo Diddley, Billy Haley and his Comets… It would have been even better, but The Platters, The Drifters and The Coasters couldn’t sort out work permit issues. Hence, some of the eventual support card was baffling and unpopular (Detroit garage-rock noiseniks the MC5, The Glitter Band), but no-one had come to see them anyway.

The show took its cues from 50s ‘revue’ events in many ways, with relatively short sets. The audience was a mad mixture: a new generation of Teds, leather-clad rockers with skulls on their jackets, bikers, suedeheads, longhairs… and ordinary folk who just loved rock’n’roll.

Packed With Hits

It wasn’t without faults. The stage lighting was so inadequate it was a wonder people at the back could see anything. And the sound wasn’t great. But, back then, such enormous stadium shows were in their infancy.

Bill Haley played brilliantly. Even at 47, and after a long time missing in action, he and the Comets sounded on the money. Little Richard came on and announced himself “the king of rock’n’roll” (it was his latest album’s title, after all) but he only had a small, five-piece band. He was also booed when he stopped playing just to stand on top of his piano, remove his mini vest and throw it to the crowd. When interviewed in Peter Clifton’s concert film, Richard seemed rankled. Partly because his audience was by then – and not just at Wembley – almost exclusively white.

Later on, Richard reflected: “I think the sound system was bad. The last outdoor engagement I played, before Wembley, was at Atlantic City with Janis Joplin, and we had 60,000 people there. The sound outdoors is never all that good. You also have to take into consideration that Wembley was not just a concert — a film was being made as well. We were told how to present certain things for the movie.”

The London Rock and Roll Show was carefully curated, true, but it was packed with hits. It didn’t really reflect what the individual artists were then playing and recording, but that was the point. At no juncture were there the dreaded words: “And now, we’d like to play you some new songs…”

Comeback Kings

And the camaraderie between these comeback kings was strong. Berry comes onstage at Bo Diddley’s finale to hold the guitar slinger’s arm aloft in salutation. Richard said “it was like meeting old friends again”. And who says Chuck Berry was irascible? His winning smile at the end of the movie is as wide as the Missouri.

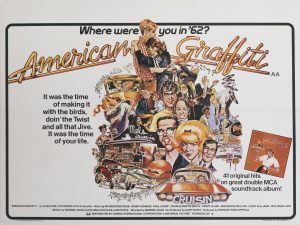

A rediscovered passion for early rock’n’roll was seeping into wider popular culture, too. A landmark came in the form of American Graffiti, the movie co-written and directed by George Lucas. It’s actually set in 1962 (suburban culture always takes a while to catch up), but the coming-of-age comedy was the unrivalled surprise hit of 1973.

A series of vignettes from one night in the life of Californian teenagers, it was produced on a $777,000 budget, yet is now estimated to have made over $200 million in box office and video sales. Stars included Wolfman Jack – the real-life DJ who had made his name on the illicit ‘border blaster’ radio stations that played R&B and early rock’n’roll – and a young Ron Howard. Although not born until 1954, Howard would soon become a totem for 50s throwbacks as co-lead in the massively popular 50s-set sitcom Happy Days.

Happy Days

In music, looking back was now becoming perfectly acceptable… if perilous. Elton John scored his first US No.1 in 1973 with Crocodile Rock, though he and Bernie Taupin got sued by Speedy Gonzales writer Buddy Kaye. “I wanted it to be a record about all the things I grew up with,” admitted Elton. “Of course it’s a rip-off , it’s derivative in every sense of the word.”

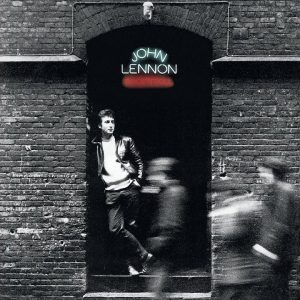

John Lennon still had a burning passion for early rock’n’roll that came out on his 1975 covers album, called simply Rock And Roll. The genesis of that LP may have been a publishing dispute, but Lennon’s genuine affection for the uncomplicated rockin’ of his childhood is clear. Ringo Starr had actually got there first: he’d topped the US Hot 100 with a remake of Johnny Burnette’s 1960 hit You’re Sixteen two years previously, and Starr’s 1970 album Sentimental Journey had gone even further, delving into pre-war songs and stopping at the 1950s.

At the pop end of the market, faux 50s-styled acts such as Showaddywaddy and Mud were soon invading the UK charts. In the US, Sha Na Na – the slightly surrealist 50s revivalists who’d performed immediately before Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock in 1969 – were still going strong and on their way to their own ratingsexploding US TV show. As they shout on their 1973 live album The Golden Age Of Rock And Roll, “We’ve got just one thing to say to you f***in’ hippies, and that is that rock’n’roll is here to stay!”

Reasons To Be Cheerful

Why did the revival happen? Well, the 60s was a decade of such upheaval, perhaps nothing felt certain anymore. The post-war boom of the 50s was a long time gone, and as the 70s dawned it had been replaced by Vietnam, boggling new fashions, bad drugs, strident sexual politics, race riots and ‘heavy’ music that sounded like doom. Although rock’n’roll was originally an outrageous rebellion itself, it now sounded positively comforting, optimistic and reliable. A good time. It’s well known that in times of trouble, we yearn for the past… the turmoil of the changing world was addressed perfectly (if cryptically) by Don McLean on his massive hit of 1971, American Pie.

The late Richard Nader explained: “I think we become nostalgic when we’re in a situation that we’re not coping with. When people bumped up against the 1970s there were many things that made them very uncomfortable. Comfortable, secure, warm, accepted – that’s all nostalgia is. All I did was give them the key, music of the 50s that made guys my age in the 70s comfortable and secure.”

In the early 1970s, the 50s revival was strong. There’d be another revival in the wake of punk. A desire for a simpler time? A way of retaining an older audience in ‘pop’? Or, maybe, a whole lotta people realised that 50s music was simply more fun…

Words Michael Leonard

Watch the The London Rock and Roll Show 1972 on YouTube here

Want more? We pick out 20 of the best British rock covers of US records