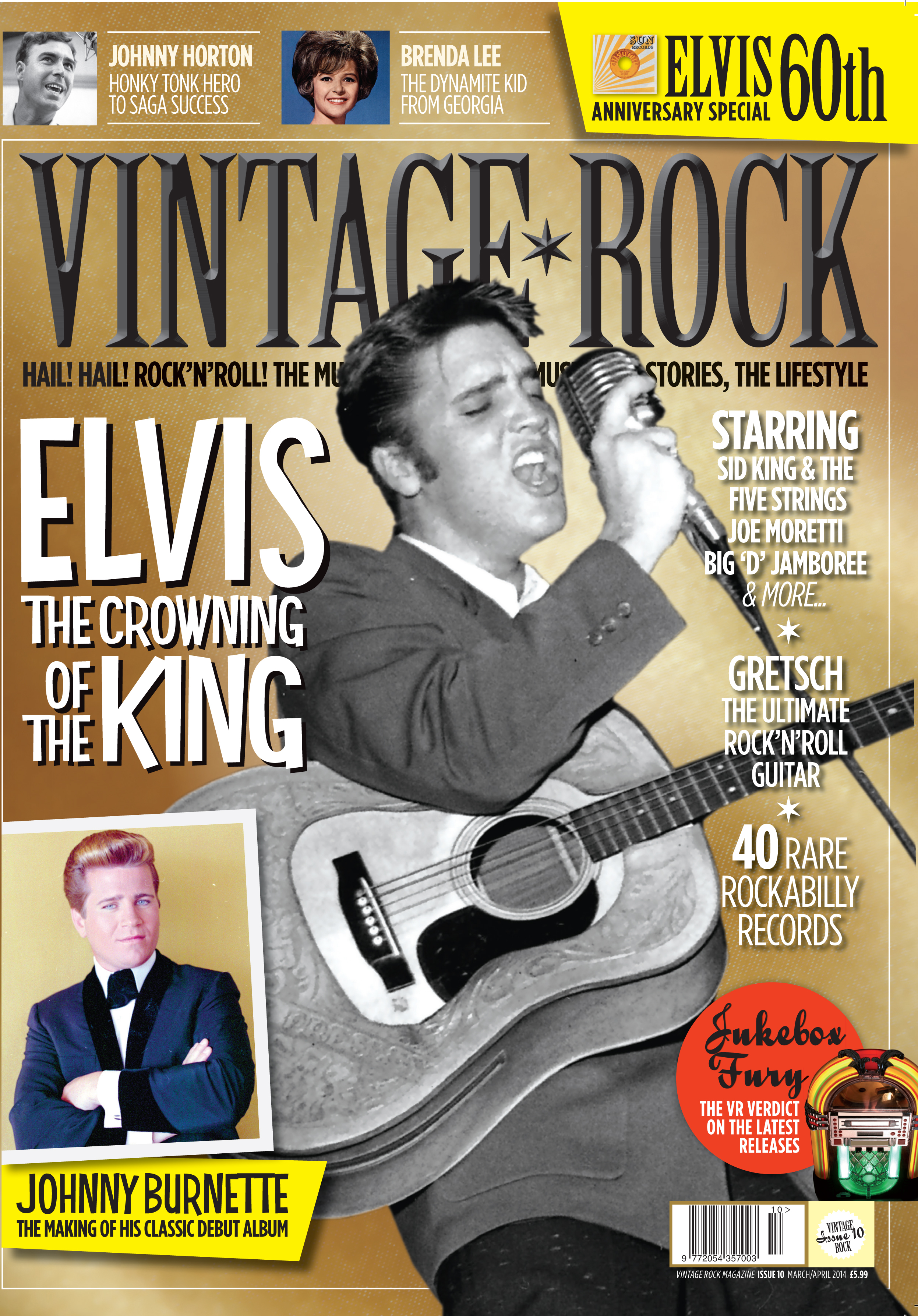

Alan Freed is credited as the man who helped popularise the term ‘rock’n’roll’ and was one of its most passionate advocates in the 1950s. Yet his career ended in scandal. Vintage Rock remembers one of the most influential DJs of all time…

Rock’n’roll has many mothers and fathers. But while those artists who helped cement it as the defining sound of the 1950s are continually referenced by the media, there are others vital to this story that history has largely forgotten. As you’re reading this magazine, it’s likely that you’re already well acquainted with Alan Freed.

He’s a figure that pops up regularly within these pages, and someone who remains a titanic name to music scholars. After all, look up ‘rock’n’roll’ on Wikipedia and Freed’s name appears more times than Elvis Presley. Stroll down Vine Street in Hollywood and there he is on the city’s Walk Of Fame, with the organisation’s website posting: “He became internationally known for promoting African-American rhythm and blues music on the radio in the United States and Europe under the name of rock and roll”.

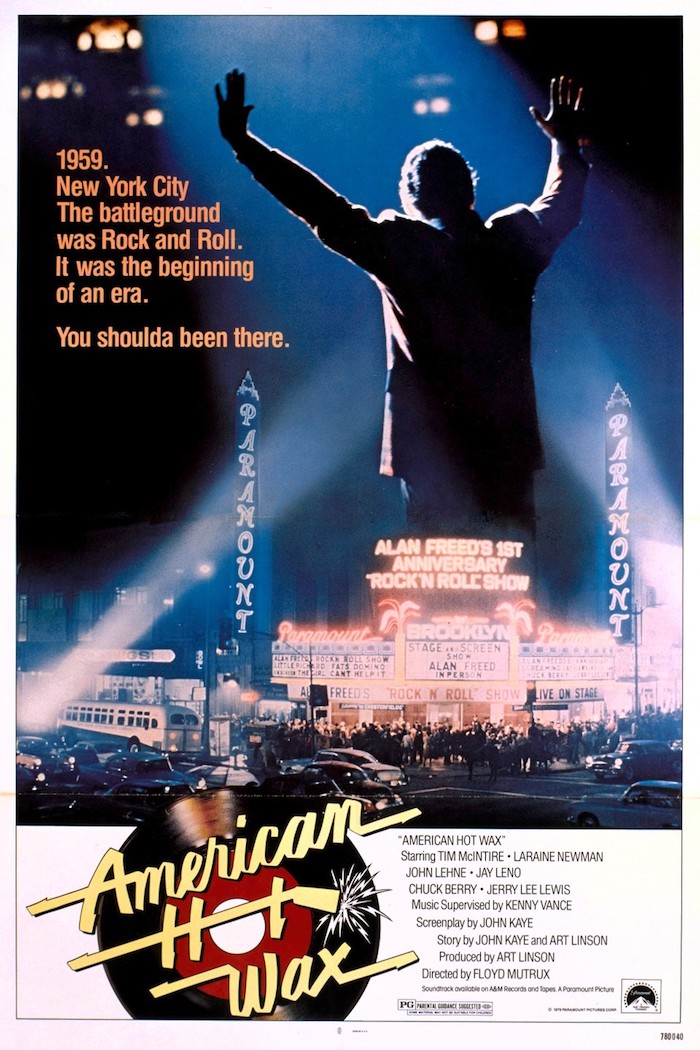

Yet for all these honours, Freed’s name remains barely known to the general public. Despite being integral to the growth of rock’n’roll and for popularising the term itself, he remains a figure known primarily to the hardcore devotee. When Hollywood did get round to making a big screen biopic of Albert James ‘Alan’ Freed (in the form of 1978’s American Hot Wax) it was an almighty flop. However intrinsic Freed was to rock’n’roll, he was, in the eyes of the movie-going public, just a DJ without the sex appeal or blistering charisma of an Elvis or Jerry Lee Lewis.

Rock And A Hard Place

Yet Freed’s legacy is a complex one. He may be extolled by music fans as the DJ who did the most in the 50s to familiarise white audiences to Black music, but his career is forever tainted by the payola scandal of the latter part of that decade. He initially denied taking money from record companies to spin certain discs, but eventually confessed, pleading guilty to two counts of commercial bribery. And while many of those rock’n’roll firebrands, from Little Richard and Chuck Berry to Jerry Lee Lewis, all lived into their eighties and nineties, it was Alan Freed, the humble DJ, who died young, passing away at just 43.

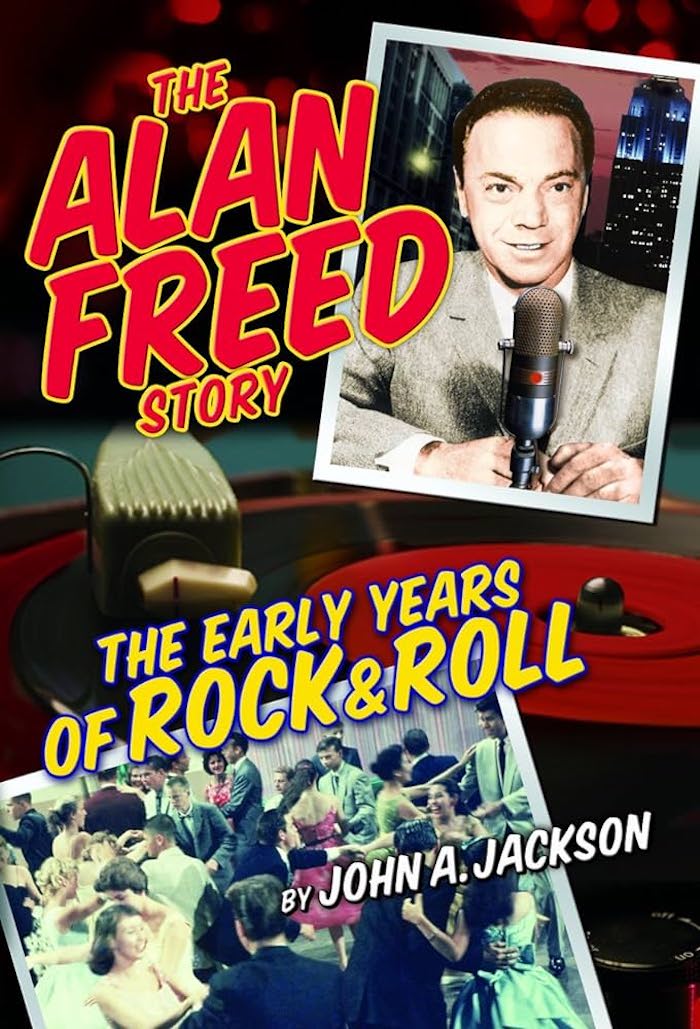

“There’s a line in the 1962 movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance which counsels: ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend’,” John A. Jackson, author of The Alan Freed Story: The Early Years Of Rock & Roll, tells Vintage Rock. “With Freed, it’s not that cut and dried. His legacy has evolved into a complicated cocktail of legitimate accomplishments leavened by fantasy and wishful thinking. But one thing is certain: he is the person who introduced Black rhythm and blues to white America.”

The Real Deal

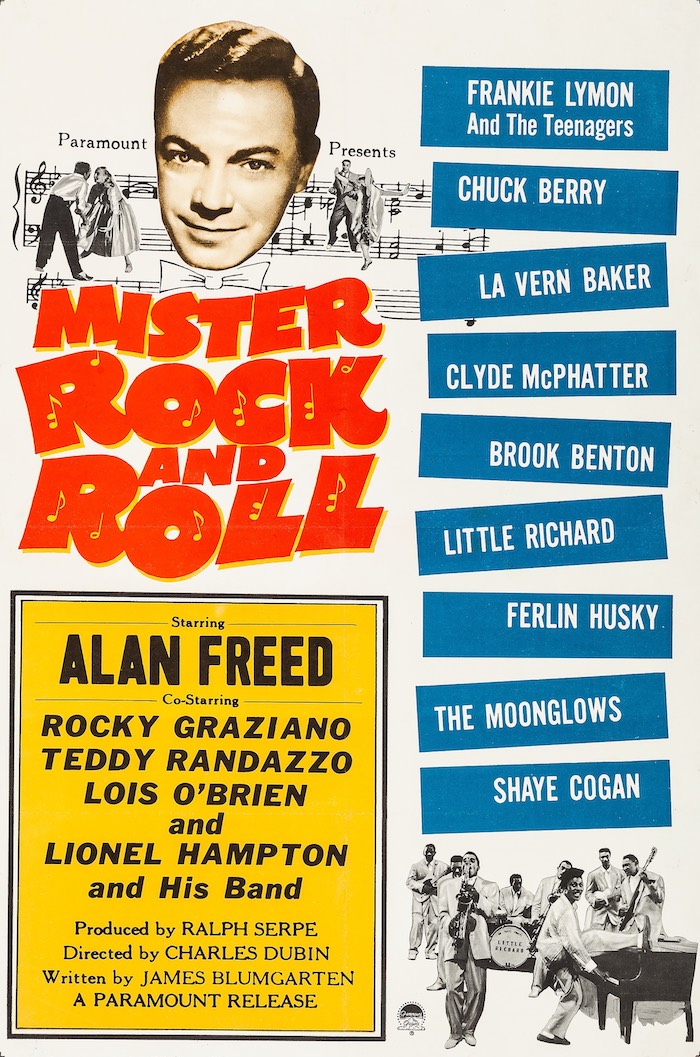

Looking at photos of Freed in his prime, he appears an unlikely champion of this unruly movement. He seems more like a clean-cut 40s-style bandleader, in his neat, chequered jacket and ever-present bow tie, yet his radio persona had the same kinetic energy as this fresh, new music. Teenagers can spot a fake from 100 miles and they knew instinctively that Freed was the real deal.

He may have been in his thirties when he started broadcasting these seditious 45s, but it was clear he loved the music and was on the side of the young. “They’re not bad kids,” he said after one particularly raucous event he’d compered. “If the theatre gets a few broken seats, that’s their problem.”

On The Air

For all of his anti-establishment spirit, Freed’s life before rock’n’roll, was thoroughly unremarkable. He was born in 1921 to a Welsh-American mother and a Russian Jewish immigrant father in Windber, Pennsylvania.

At school he was the trombonist in a band, The Sultans Of Swing, and after university served in the US Army, securing a job on their radio service. After the war, he worked at a succession of small radio stations – WKST in Pennsylvania, WKBN in Youngstown, Ohio and WAKR in Akron, Ohio. He hadn’t yet discovered the music that would come to define his career, working variously as a sportscaster and a classical music DJ.

It wasn’t until he’d moved to Cleveland, to work on the city’s WJW station, that rock’n’roll entered his life. It was an encounter with a local businessman, Leo Mintz, that would change everything. Mintz was the fortysomething owner of one of Cleveland’s largest record stores, Record Rendezvous, and was among the first to notice the increasing interest in Black R&B. With Mintz’s encouragement, Freed started spinning these revolutionary 45s on the air.

King Of The Moondoggers

He named his new show The Moondog House, the title deriving from an instrumental titled Moondog Symphony by New York-based composer and street musician Louis T. Hardin, known professionally as Moondog (Hardin later took Freed to court for copyright infringement, collecting $6,000 and an agreement from Freed to stop using the name).

Hardin’s piece opened the show, and Freed would dub himself ‘The King of the Moondoggers’. It was on this show that he began referring to these tracks, then popularly known as ‘race records’, as ‘rock’n’roll’. The term wasn’t new, of course – since the 1920s, it had been a much-used euphemism for either dancing or sex, with Trixie Smith’s 1922 blues ballad My Man Rocks Me (With One Steady Roll) typifying its meaning for the next 30 years.

But Freed’s continued use of the phrase during his show certainly popularised it as the catch-all term that encompassed the R&B and hyped-up country he was playing to his listeners. And it was a style he replicated himself. Whereas most DJs of the time were subdued and staid, he brought all of rock’n’roll’s zest and zing to his patter, ringing cowbells and howling when he found a record he loved. To his listeners, Freed was as hip and exhilarating as the revved-up blues that he was playing.

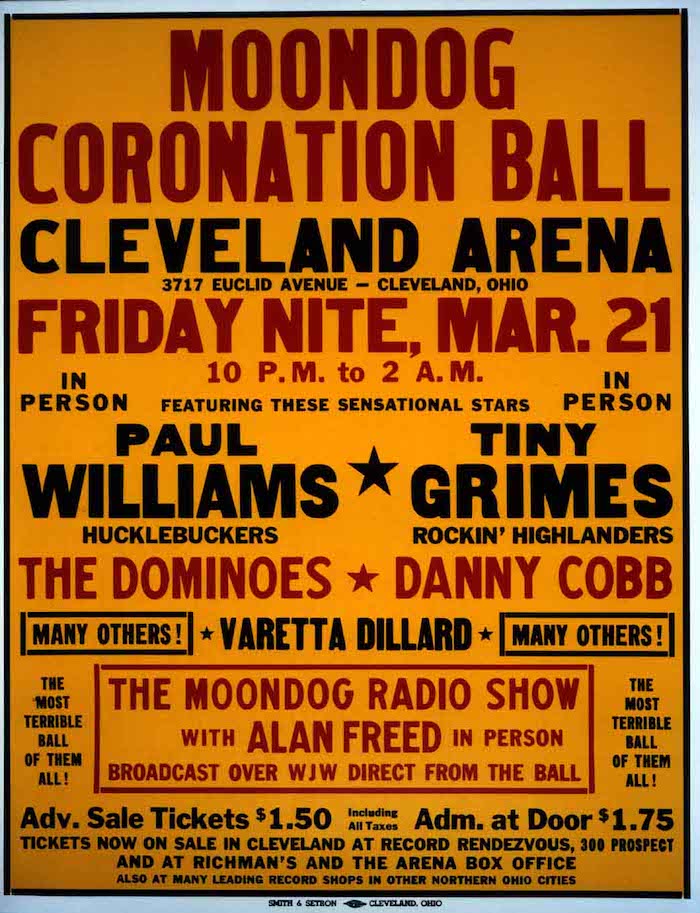

Having A Ball

Freed’s show proved so popular that in 1952, he set up The Moondog Coronation Ball, a multi-act live event held in the city’s Cleveland Arena, now generally accepted as the first major rock’n’roll concert. It was, depending on your point of view, either a roaring success or an unmitigated disaster. More kids attended than the organisers had ever planned for and a riot ensued. The event’s notoriety helped fuel the idea of rock’n’roll as a clear and present danger, yet it certainly didn’t harm Freed’s career, helping identify him as the genre’s most charismatic and passionate advocate. After the debacle of The Moondog Coronation Ball, Freed saw his ratings soar.

“Prior to that shocking event, Freed was a virtual unknown in the broadcasting business,” Jackson tells us. “Both Billboard and Cash Box published follow-up stories about this unheard-of disc jockey and the mind-boggling crowd he generated, basically by using his Moondog House programme – and nothing else – for publicity. Everyone in the broadcasting business read Billboard and/or Cash Box on a weekly basis. Nobody at the time had any idea who or what a ‘Moondog’ and/or his ‘Coronation Ball’ was, but in one fell swoop Freed had unwittingly thrust himself onto the broadcasting map. Within less than two years, he was headed to New York and 50,000 watts of broadcasting clout.”

Movie Magic

In The Big Apple, Freed joined the city’s WINS station, followed by a move to CBS radio and then WABC (AM). By now his name was so wedded to the rock’n’roll phenomenon that figures within the music industry would attempt to curry favour with the increasingly influential DJ. Leonard Chess offered Freed a piece of the songwriting credit on Chuck Berry’s ’55 debut Maybellene (much to the consternation of Berry himself) as well as on The Moonglows’ hit Sincerely.

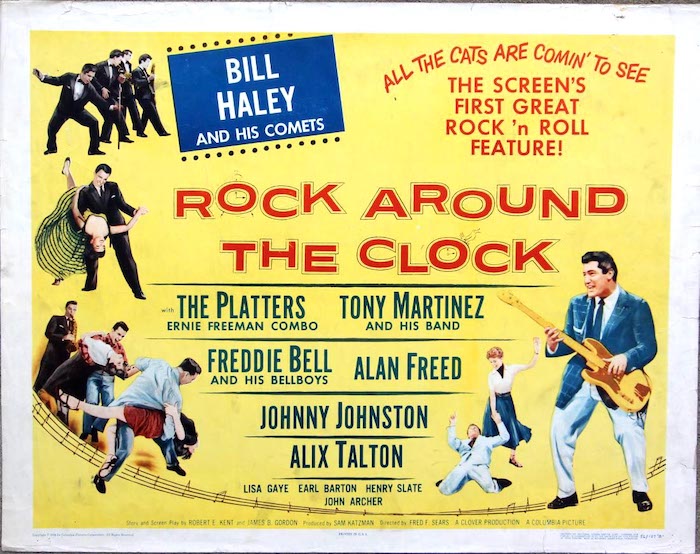

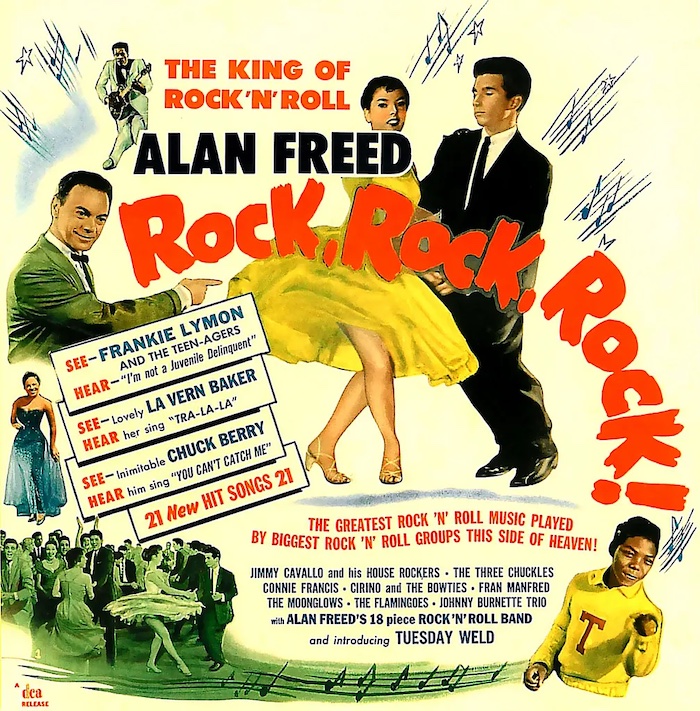

He was also being courted to feature in various rock’n’roll-themed movies, appearing as himself in Rock Around The Clock (in 1956), that same year’s Rock, Rock, Rock, as well as Mister Rock And Roll and Don’t Knock The Rock (both 1957). He even conquered TV in 1957 when he was given a weekly primetime show on ABC titled The Big Beat, only for it to be axed after the Black performer Frankie Lymon was filmed dancing with a white member of the audience.

Under The Counter

In the late 50s the idea of bribing prominent DJs to playlist certain songs wasn’t yet illegal. Yet it was widespread. Hy Weiss, owner of New York City’s Old Town Records, became known as the owner of ‘the $50 Handshake’, in reference to the manner in which he got artists on the radio. Chicago DJ Al Benson, meanwhile, would shamelessly charge local record distributors for airplay, allotting each airtime related to the company’s size.

But as the preeminent figurehead of the rock’n’roll revolution, Alan Freed was a high-profile target for the US Congress when they began investigating payola, after their headline-grabbing inquiry into rigged TV quiz shows. Many DJs were fired or quit, and WABC (AM), where Freed had found himself by 1959, demanded all their DJs sign a statement for the Federal Communications Commission that they had never accepted bribes. After refusing, the station fired him. In December 1962, after being charged on multiple counts of commercial bribery, Freed pleaded guilty to two counts and was fined $300 and handed a suspended sentence.

Freed wasn’t the only DJ to accept payments from record labels, but he was the most prominent victim of the investigation. His reputation in tatters, he found work hard to come by in the years after. A job at WQAM in Miami lasted just two months. He later moved to L.A., but by then had developed a drinking problem and died on 20 January 1965, from uremia and cirrhosis brought on by chronic alcoholism, at the age of 43.

Rock’n’Roll Radio

Though the public has largely forgotten Alan Freed’s name, those in the know have continued to sing his praises. For director Floyd Mutrux’s 1978 biopic of the great man, American Hot Wax, Chuck Berry, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Frankie Ford and Jerry Lee Lewis all agreed to cameo as themselves, while in 1986 he was among the first group inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

Freed was awarded his Walk Of Fame star in 1991 and in 1999 he was the subject of another biopic, this time a made-for-TV movie, Mr. Rock ’n’ Roll: The Alan Freed Story, starring The Breakfast Club’s Judd Nelson as Freed. Listen to the Ramones’ Do You Remember Rock’n’Roll Radio? and there’s a nod to him (“Do you remember Murray the K/ Alan Freed, and high energy?”) and he’s namechecked by artists as diverse as Marc Bolan, Public Enemy, Neil Diamond and Kill Your Idols.

Jockey’s Jukebox Musical

Last year, Freed was the subject of an off-Broadway play titled Rock And Roll Man. It premiered in June and was soundtracked by artists such as Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, LaVern Baker, Bo Diddley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, along with original songs composed by Gary Kupper.

In the play, Freed was played by actor and singer Constantine Maroulis. Maroulis became well known by appearing on the fourth season of the reality TV show American Idol, and later received a nomination for the Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical for his role in Rock Of Ages.

According to the press release, “the musical takes place on the final day of Freed’s life. In a fever dream, prosecutor J. Edgar Hoover and defence attorney Little Richard face off with Freed’s legacy at stake.”

“After such massive contributions, I didn’t know the sort of layered life that he led,” Maroulis told NJ Advance Media. “He was a flawed man but a good family guy. And certainly, just passionate about the music and the artists and just something I related to. And it just jumped out at me – the opportunity to create a role.”

In November, the production was named Best Musical at the 51st Audelco Awards and Covington claimed the Best Featured Actor In A Musical accolade.

Genuine Enthusiasm

When Alan Freed’s name does crop up, it’s to credit him either with inventing the rock’n’roll tag (he didn’t) or popularising it (which he most definitely did). Rock’n’roll was happening anyway, but the speed in which it caught on certainly had a lot to do with the impassioned advocacy of Freed. His acute cultural antennae and genuine enthusiasm for this radical, incendiary music eased it into the homes of those who might never have stumbled across it. And that alone makes him one of the forefathers of rock’n’roll.

“Alan Freed did more than any other individual to promote Black R&B to white America,” says Jackson. “Without his efforts, rock’n’roll music would have eventually emerged in one form or another – with a different name, of course.”

For further information on the Rock And Roll Man musical click here

Read more: When rockabilly shook the world

Sign up to the Vintage Rock Newsletter