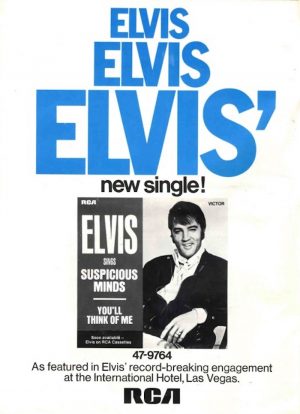

In 1969, Elvis recorded one of the biggest tracks of his career, Suspicious Minds. Douglas McPherson discusses the landmark recording with songwriter, Mark James

According to songwriter Mark James: “When Elvis came to American Sound Studio, I think he was hesitant, because it was like backing up.”

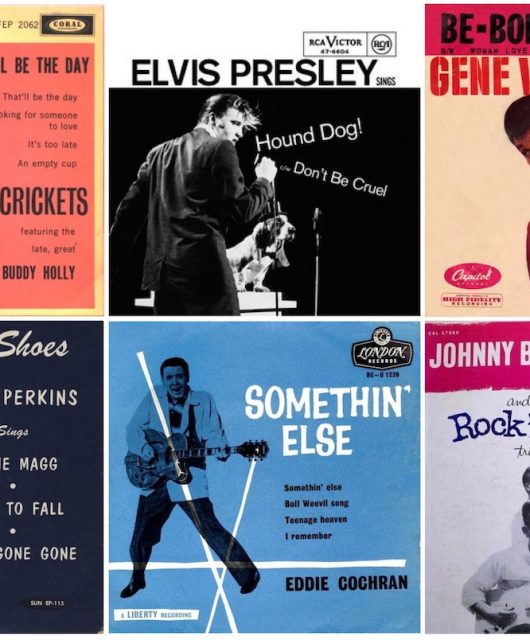

Although Elvis had begun his career at Sun Records in Memphis and, indeed, had almost single-handedly put the city on the map as the birthplace of rock’n’roll, 13 years had elapsed since he’d last taped a note there, at an informal jam with Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash, an impromptu session that became known as the Million Dollar Quartet.

“He’d gone to Hollywood and recorded in different places – big studios,” James continues. “So he was probably a little uneasy about coming back to Memphis, wondering ‘Should I do this or not?’ But a lot of his friends talked him into it and, of course, there was a lot of great music coming out of Memphis at that time. So he came down and booked the studio for two weeks and 40 songs.”

Comeback Special

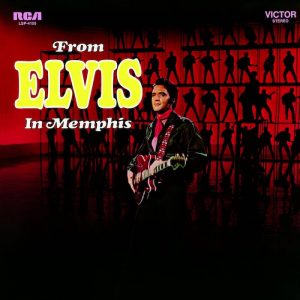

The result was one of the most acclaimed albums of Presley’s career, From Elvis In Memphis, and four hit singles – including two songs that completely revived his reputation as an artist: In The Ghetto and Mark James’ composition, Suspicious Minds – Elvis’ first No. 1 single in seven years and often voted in fan polls as the greatest song he ever recorded.

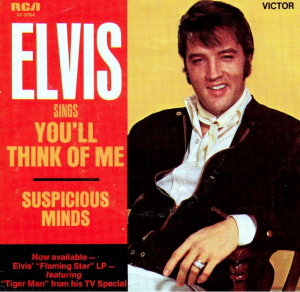

Elvis’ return to the Bluff City in January 1969 was intended to capitalise on the critical success of his TV special, Elvis, which had screened in December. The programme had re-established the king as a potent leather-clad rocker as opposed to the purveyor of innocuous movie songs that he’d become during the previous decade. To maintain momentum, he needed new hits.

Fans can only speculate on what might have happened if Elvis had been reunited with his original producer, Sam Phillips, at the fabled Sun Studio. By the mid-60s, however, Phillips had lost interest in recording to concentrate on other business interests, including radio stations. The original Sun Studio on Union Avenue would stand closed and silent until the 1980s.

So Elvis headed to the hit factory that was American Sound Studio where he was teamed with arguably his best producer since Sam – Chips Moman.

Midas Touch

Chips, whose real name was Lincoln Wayne Moman, got his nickname from a fondness for poker. The producer, who died on 13 June 2016, had the word ‘Memphis’ tattooed on his arm, but he was born in LaGrange, Georgia. He moved to Memphis in his mid-teens and found work as a house painter. His entry into the music business came by chance when Sun recording artist Warren Smith heard him strumming a guitar on a work break. Warren invited Moman to back him at a gig, on a bill that included Carl Perkins and Roy Orbison.

Before long, Moman was picking in Gene Vincent’s band before turning to songwriting and producing, and becoming one of the founders of Stax Records. Moman produced Stax’s first major hit, Gee Whiz by Carla Thomas, but fell out with the company and split to found his own American Sound Studio. His first hit was Keep On Dancing by The Gentrys, which gave him sufficient funds to hire a secretary – one Sandy Posey, who Chips would soon turn into a star in her own right.

At American Sound, he had a musical Midas touch and helmed hits by Bobby Womack, Wilson Pickett and The Box Tops. Yet when he’d set up shop, he’d been strapped for cash, and had picked the cheapest premises he could find in the roughest part of south Memphis.

Diamond In The Rough

By the time Elvis arrived at 827 Thomas Street, neither the small, shabby studio nor the surrounding neighbourhood were remotely fit for a king. In fact, the rat-infested building was guarded by dogs and had a man with a gun stationed on the flat roof to keep an eye on the car park.

Moman bumped Neil Diamond out of a previously booked recording appointment in order to accommodate Presley. But, surprisingly, he would later state: “To be honest, I didn’t really think there was anything that special about getting the chance to record Elvis. We were just so busy producing records in Memphis back then and a lot of ’em were hits. Almost everybody in Memphis took Elvis for granted and didn’t pay much attention to how big a star he really was.

Country-soul Sound

“Later, I thought to myself, it sure was a privilege to have worked with him. I wish I had realised that at the time, ’cause there’s a lot of things that I would have liked to have said to him.”

The fact that Moman wasn’t in awe of Elvis probably helped him to get the best out of the singer. “When I told him he was off pitch, his whole entourage would nearly faint,” the producer recalled. A lot of the material laid down in the American Sound sessions was country, including John Hartford’s oft-recorded Gentle On My Mind and the old Eddy Arnold ballad I’ll Hold You In My Heart (Till I Can Hold You In My Arms). Filtered through Elvis’ vocals and the horn-laced sound of Moman’s house band The Memphis Boys, the results were country-soul, as epitomised by the heartfelt True Love Travels On A Gravel Road.

The emphasis on country was because of an arrangement through which Presley and his management got a split of the proceeds of songs published by Hill & Range, which specialised in country. Moman wasn’t overly impressed by the arrangement, and later commented: “There was a lot of them old Hill & Range songs that some of the people around him wanted him to cut real bad, and they kept pushing for them. I don’t even want to tell you what I thought of some of those songs!”

Moman was more interested in having Elvis cut contemporary tracks such as In The Ghetto – on which Moman, perhaps not coincidentally, happened to own the publishing rights himself!

Message Songs

Presley’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker, on the other hand, didn’t think Elvis should be recording ‘message songs’ like In The Ghetto. But having gone against the Colonel’s advice to sing the civil rights-inspired If I Can Dream as the finale of the ’68 Comeback Special, Elvis had vowed that he would, from that point on, only record songs that he truly believed in.

Cutting In The Ghetto was part of his resolve to assert his artistic independence and became one of the cornerstones of his return to critical acclaim, when the song reached No. 3 on the charts to become his first Top 10 hit in four years.

As for Suspicious Minds, which would build even higher on Ghetto’s success, Mark James had been desperately trying to write a song for Elvis from the moment he heard Presley was coming to the studio. James was an in-house writer at American Sound and was riding high on the success of the BJ Thomas hits Eyes Of A New York Woman and Hooked On A Feeling. The songs had revived Thomas’ career, and James was determined to do the same for Elvis. “First of all, I asked myself, can Elvis come back?” James recalls.

“I thought, how old can you be and be a rock’n’roll artist? I thought about Tom Jones, because he had his TV show and he was number one at that time. Elvis had done movies and movie songs, and that wasn’t really competing with the Top 40 – he’d lost his ground there and Tom Jones had taken over. But in my mind, I bet on Elvis – I thought he could come back.

Golden Sledgehammer

“I started thinking, what kind of song?” James continues. “I was thinking it would have to be a mature rock song…”

For all his analysis, however, James couldn’t come up with anything, and the clock was ticking down to Elvis’ arrival “Chips had a business partner called Don Crews,” James recalls. “Each time I saw him at the office next to the studio, he’d say, ‘You come up with anything for Elvis?’ ‘No, no, not yet…’

“It got down to two days before Elvis was due to come in, and I said, ‘I can not come up with it!’ So Don says, ‘What about your old catalogue? What about Suspicious Minds?’ I turned around in my chair and it was like I’d been hit with a golden sledgehammer. That was the song I was looking for!”

Song Fit For The King

James’ aspirations as a recording star dated back to 1959, when his group The Naturals had a local hit in Texas with an instrumental called Jive Note. He wrote and recorded Suspicious Minds as his first single on the Scepter label in 1968, although few people heard it.

“I don’t think they knew how to promote it,” James reflects. “But the bottom line is, Suspicious Minds wasn’t meant for me, it was meant for Elvis.”

Elvis was so determined to do the song justice that he spent three hours and eight takes before he was satisfied. The final version was, in fact, spliced together from three vocal takes. Moman had produced James’ single and used the same musicians to reproduce the arrangement on Elvis’ recording. The difference was that Elvis loved the song so much, he stretched it to two minutes longer than James’s single by endlessly repeating the closing lines.

“We laughed at it,” said the horn and strings arranger, Glen Spreen. “We just went, ‘God, how can they do this?’ as it kept going and going and going.”

The Elvis Tax

One person who didn’t witness the recording was the song’s writer. “I lived and breathed the studio, I was there night and day,” James recalls. “But when they started cutting with Elvis, I went into the control room to pick up a tape. Through the glass, Elvis was singing Any Day Now, and I could tell he felt real uneasy with me looking at him. I thought there and then: I cannot be here when he records my song or I’m gonna jeopardise it. It was the same room, same producer, same engineer and same musicians that played on my record. I didn’t have to be there, so I stayed away. The downside is everyone got a picture with him but me!”

Although Suspicious Minds and In The Ghetto were the highlights of the Memphis sessions, they nearly never came out, because Elvis’ people demanded that Moman sign half of the publishing rights over to Hill & Range. “I blew up and told them to get out of the studio,” said Moman.

Until that moment, it was common for songwriters to give Elvis a songwriting credit or share of the publishing in return for him cutting a song, in a deal nicknamed the Elvis tax. In a further example of his new-found independence, however, Elvis sided with Moman, realising it was better to cut the best songs for his career, rather than just those in which he’d get a share of the publishing.

Concert Centrepiece

In an interview with Memphis’ The Commercial Appeal after the session, Elvis said: “We have some hits, don’t we, Chips?” “Maybe some of your biggest,” Chips replied. The record wasn’t quite finished, though. Later that year, Elvis performed his first live concerts since 1961, when he appeared for four weeks at the International Hotel in Las Vegas. Although Suspicious Minds had yet to be released, he made it the centrepiece of his shows, extending the number to seven minutes long by fading it out and then dramatically returning to finish it.

Elvis’ regular producer, Felton Jarvis, had let Moman take charge in Memphis, although he had also been present. But noting the audience reaction to the way Elvis performed Suspicious Minds on stage, he decided to add his own fade and resurgence near the end of the song, before it was released.

Moman didn’t appreciate Jarvis’s contribution, saying: “He messed it up. It was like a scar.” Reportedly, some disc jockeys also disliked the false end and the song’s overall length. The emotion that Elvis poured into his performance, however, was undeniable and unstoppable – and perhaps the novel fade that he invented on stage and Jarvis replicated on the record added its own magic, suggesting he really was, as he sang, “Caught in a trap…” and couldn’t walk out.

Perfect Fit

Within two months of the single’s release in late August, the King was back at the top of the charts for the first time in seven years, with a song that would sell nearly two million copies.

Probably because of the clashes between Moman and Presley’s handlers, Elvis never returned to American Sound Studio and Suspicious Minds became his last No. 1 during his lifetime. He did, however, record several more songs by Mark James, including Moody Blue and Always On My Mind.

“I never wrote a song for Elvis,” James reflects. “It was just that my songs fit him somehow. I think it was because we were both from the South, we both loved rock and all kinds of music. Elvis’ friend, the disc jockey George Klein said I was Elvis’ favourite writer. The mail would come in, and he’d say, ‘Any Mark James songs?’”

Read more: When rockabilly shook the world