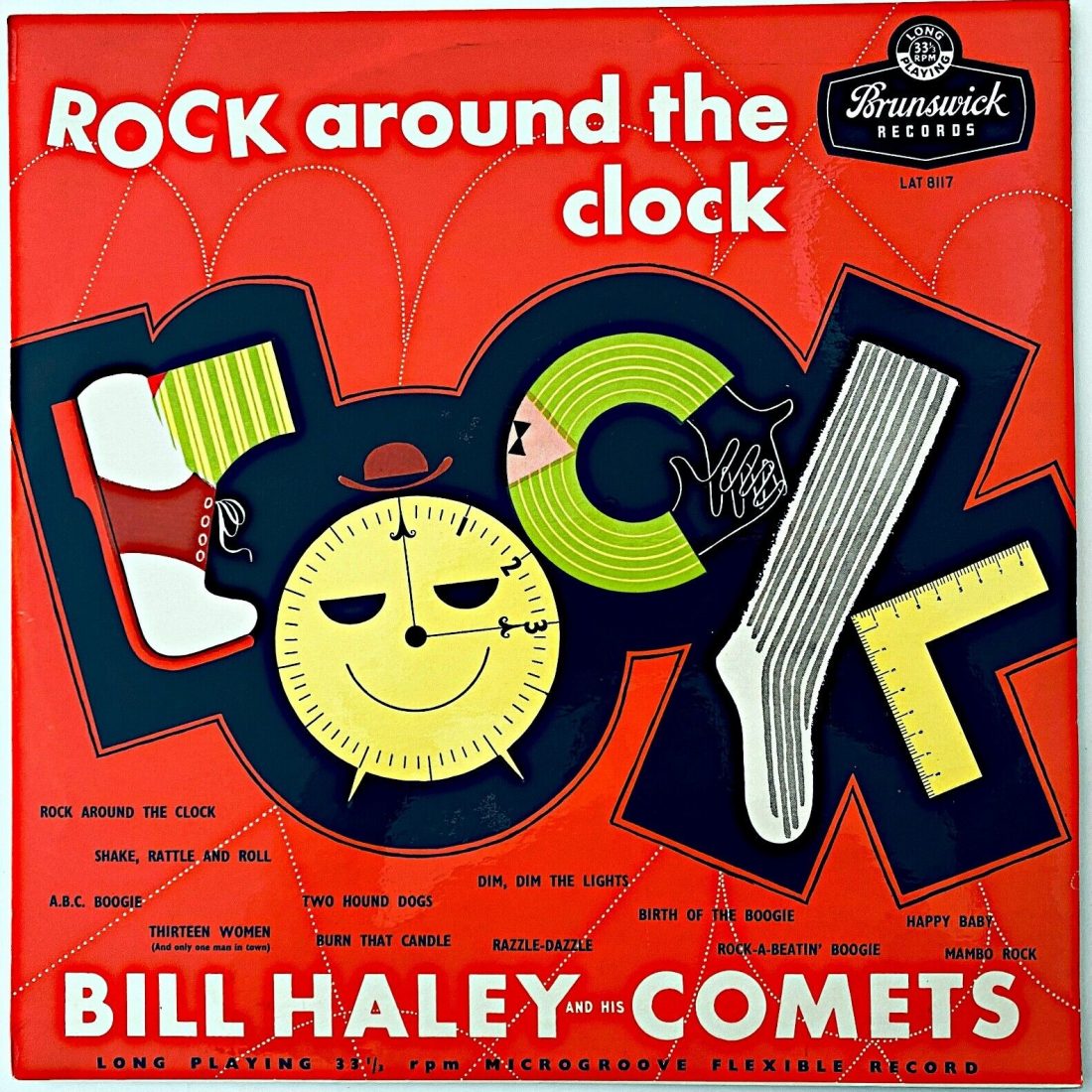

Released at the height of Bill Haley’s popularity on both sides of the Atlantic, Rock Around The Clock was a compilation album stuffed full of what has come to be seen as some of his finest rockers… By Jack Watkins

The historic significance of Bill Haley’s (We’re Gonna) Rock Around The Clock single has been well documented. Much less discussed is his album of the same name, unsurprisingly in that it was not a specially studio-crafted LP, but a compilation of recordings Haley made with the Comets for Decca, from shortly after they joined the label in April 1954 up to September 1955.

However, after its Stateside release at the end of 1955, it climbed to No.12 on the Billboard pop album chart. Then, when released in the UK the following summer, it did even better, reaching No.2 on the British equivalent. This made it, just ahead of Elvis Presley’s eponymous debut album, effectively the first rock’n’roll long-player to make a serious dent on the charts.

While the album track running order didn’t follow the sequence of releases chronologically, the LP brought together each side of Bill Haley’s first six Decca singles, drawn from seven sessions. These produced a body of work that amounted to the pinnacle of the band’s most commercial offerings.

Haley signed to Decca in early 1954, partly because of the failure to achieve a follow-up success to his first national breakthrough in April 1953 with the single Crazy Man, Crazy on the small Philadelphia label Essex Records, and partly in frustration at the refusal of that company’s owner and producer Dave Miller to allow him to record Rock Around The Clock.

James Myers, a Haley associate and music publisher, claimed to have written the song under the pseudonym Jimmy DeKnight with Tin Pan Alley songsmith Max Freedman, but a personality clash between Myers and Miller had frustrated Haley’s attempts to record it. The original version was eventually laid down by Sonny Dae And His Knights, but Myers remained convinced it was the perfect song for Haley. Just five days after his Decca contract was signed, Bill and his band would be in New York recording what would become the definitive version.

As Nick Tosches put it in his book Unsung Heroes Of Rock’n’Roll, Haley was “one of the first instances of a white boy really getting down to the art of hep.” His thrilling new rock’n’roll sound and crowd-pleasing stage show had already reached full formation at Essex where, with his tireless experimentation with sound, he “was like a scientist putting one thing after another into a test tube,” as his long-serving steel guitarist Bill Williamson put it.

Even so, Decca, as one of the big five record labels, represented a considerable step up. It also brought Haley into the orbit of A&R man Milt Gabler. Although Gabler was steeped in jazz, having worked with the likes of Lionel Hampton, Woody Herman and Billie Holliday, unlike a lot of veteran A&R men in the 50s, he was also attuned to the rhythms of R&B, and had helped shape some of Louis Jordan’s best jump blues sides.

The venue for the Decca recordings was the memorably named Pythian Temple, an old New York ballroom. It had retained its wooden floor, and had a stage at the back, along with a small control room and an echo chamber where the natural acoustics created by the ballroom’s high ceiling were enhanced by a reverb effect. Gabler’s method for recording Haley and his band was straightforward – The Comets were placed on the stage.

As a live act they were notable for playing extremely loud, and Haley’s likeable, yet relatively thin voice, often struggled to be heard above them. So Gabler placed him on the ballroom floor facing the band and a few feet below them, singing directly into his own microphone. The one-track recordings were effectively done live with minimal retakes, a mic set in front of each instrument with no use of separating boards between them, and minimal tape splicing by Gabler after the sessions were completed.

Gabler later recalled that Haley and his band weren’t trained musicians and had to rehearse hard to learn songs by rote, but “boy, when they had that down it used to rock.” At the first session, Danny Cedrone’s scattergun solo on his Gibson for Rock Around the Clock was identical to the one he’d delivered on Haley’s version of Rock The Joint, recorded two years previously when the band were still a drummerless line-up known as The Saddlemen.

Now, his guitar, alongside Billy Williamson’s steel guitar notes that Gabler described as “lightning flashes,” the echoing crack of Billy Gussak’s snare drum rimshots, fired off on the backbeat, Joey Ambrose’s tenor sax, Marshall Lytle’s string bass and Haley’s hard-strummed guitar and good-time vocals, all came together to create just over two minutes of magic. This noisy recording would come to be seen as the moment when rock’s fusion of hopped-up country music and African-American rhythms truly arrived as a nationwide and, ultimately worldwide, phenomenon.

However, the breakthrough didn’t come immediately. Gabler had actually spent most of the session getting the band to record Thirteen Women (And Only One Man In Town), thinking it could take off with its topical reference to the H-bomb. It is indeed a much better song than has sometimes been suggested, a sauntering, atmospheric jazz-blues hybrid with an eerie air, but by putting it on the topside, it meant Rock Around The Clock went relatively unnoticed, selling a respectable but unremarkable 75,000 copies on first release.

DJs just weren’t interested, said Haley, recalling their standard response was, “If you want money, my car or even to borrow my girlfriend, you can have it, but please don’t ask me to play your record.” Their tune changed when Rock Around The Clock was used as the theme song to the teen rebellion flick Blackboard Jungle the following year. After Decca’s hurried re-release, teens lined up to buy it, allowing the song to really take off, hitting the top spot in the US in May 1955.

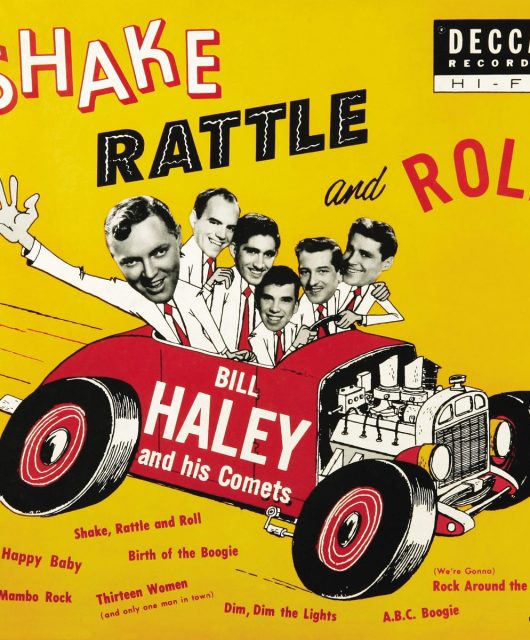

But a version of Joe Turner’s Shake, Rattle And Roll, recorded by the band at their second Decca session a couple of months later, had already given Haley his first million seller by then. This was effectively a cover, as Turner’s song was still on the R&B charts at the time, but with Billboard running an ad which described them as “The Nation’s ‘Rockingest Rhythm Group”, Haley and the Comets’ version, backed by ABC Boogie, raced up the pop chart, reaching No.7 in August 1954. Tragically, Danny Cedrone would not be around to see the success of either song, after a fatal accident when he fell down the stairs at his home and broke his neck.

Haley, though visibly moved at Cedrone’s funeral, had little trouble in finding a replacement guitarist. Franny Beecher was an ex-member of the Benny Goodman band who worshipped bop maestro Charlie Christian. He was well able to replicate Cedrone’s historic licks. However, when he turned up at the band’s next session, and started ad-libbing a jazzy solo as they rehearsed Happy Baby, he was pulled up by Haley. “I played the first four bars and everything came to a halt,” Beecher remembered, “Haley said he’d never sell any records if I played like that. I had to stick to the major chords – no flatted fifths or anything like that.”

The band played so loud Beecher also had to replace his favoured Epiphone guitar for a Les Paul. Happy Baby, paired with Dim, Dim The Lights pitched up outside the Top 10, while the follow-up, Birth Of The Boogie/Mambo Rock just made the Top 20. Haley would say of the latter when they played it live, “Not quite so much mambo, but just enough so we could call it that!” By this time, Dick Richards had joined as drummer, playing tom toms on Birth Of The Boogie, the song’s monster opening rumble reminiscent of the big sound the Goodman band created at the famed Carnegie Hall concert of 1938. Listen to Marshall Lytle’s rumbling bass. The intro the Stray Cats used to Runaway Boys 25 years later sounds suspiciously similar.

The success of the re-release of Rock Around The Clock helped drive the next single, Two Hound Dogs/Razzle-Dazzle, up to No.15 in the US, occupying the charts for a month. The former track featured the Comets yelping and howling like dogs over the fade. Razzle-Dazzle was featured in the “troubled teen” movie Running Wild, starring Mamie Van Doren, reaffirming rock’n’roll’s link in the minds of many adults with juvenile delinquency, much to Haley’s dismay.

By the next time the band went into the studio, three of the Comets, Ambrose, Lytle and Richards, had decamped to form their own Comets soundalike group The Jodimars, after a salary disagreement. Jazz saxophonist Rudy Pompilli replaced Ambrose, Al Rex who’d played in Haley’s band in the early 50s, came back in on bass, and Cliff Leeman, another jazz veteran, played drums on the session yielding Rock-A-Beatin’-Boogie. The latter showed Beecher and Pompilli already linking up well with a call-and-response passage.

Haley had originally written the song and given it to The Treniers, who influenced the Comets’ stage presentation, and who recorded the song for Okeh. Burn That Candle showcased Haley’s likeable, jaunty tones, so suited to the upbeat, fun nature of his patented rock’n’roll sound. It took him back into the Top 10 towards the end of 1955, in December of which Downbeat magazine’s annual poll had named him as their No.1 Rhythm and Blues Personality Of The Year.