We take a look at the rockin’ roots of the original Bond score composer, John Barry… By Julie Burns

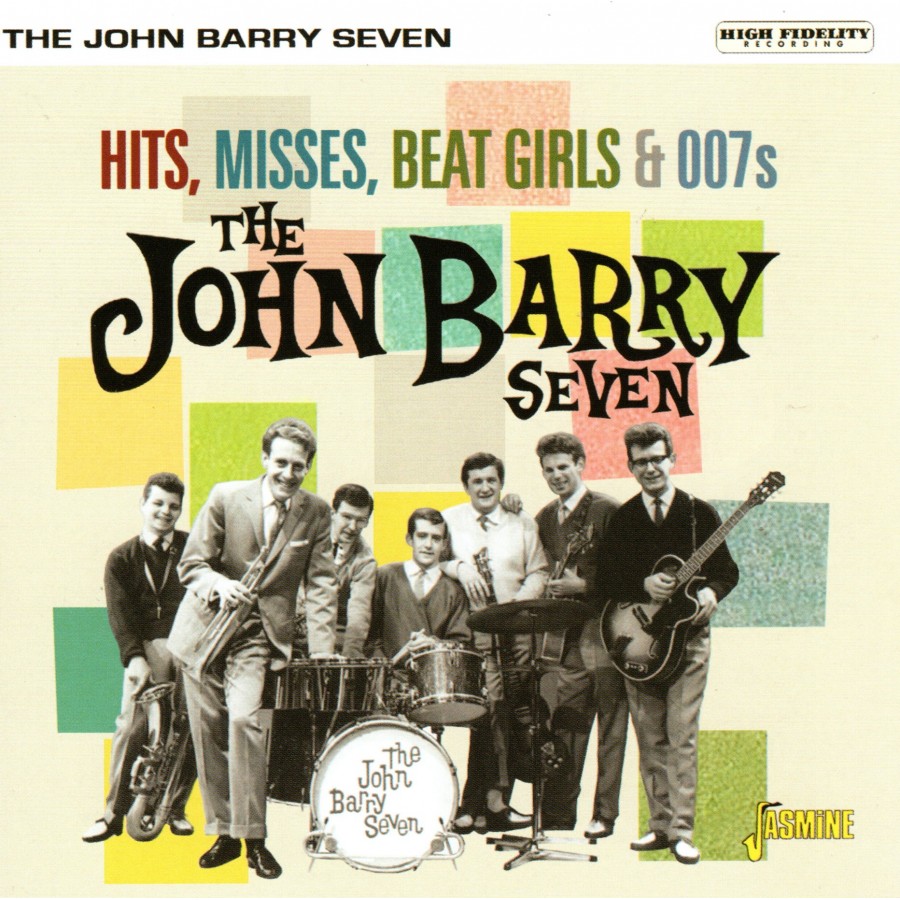

Before all those box-office gold Bond soundtracks – plus the subsequent roll call of killer film compositions – John Barry was the have-a-go hero of pre-Beatles British rock’n’roll. Yet his contribution remains largely overlooked. From 1957, as founding member of The John Barry Seven, the shy Northerner was in the vanguard of young musicians, creating their own homegrown version of the dynamic new music that was sweeping in from the States.

Barry’s original prowess as a performer, producer, arranger and writer soon shone through. Several notable self-penned hits – from the Juke Box Jury TV theme tune to a twangy cover with guitarist Vic Flick of The Magnificent Seven – led to him arranging for singer Adam Faith, before rocking his first film score, 1960’s Beat Girl.

Born John Barry Prendergast in York on 3 November 1933, he was the youngest of three. His English mother was an accomplished classical pianist and his Irish father, John Xavier, a projectionist during the silent film era, who later owned a chain of eight cinemas in the north of England. In the gloom of the post-war era, these ‘picture palaces’ acted like catnip to the locals.

Being immersed from an early age in such magical surrounds influenced Barry’s musical direction. Multi-tasking around his family’s empire, he became a proficient projectionist, but it was the music of the movies that really inspired him. Childhood highlights, he later recalled, included Max Steiner’s The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre, and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s The Adventures Of Robin Hood.

“The most extraordinary score ever” he considered to be Anton Karas’s zither-laden theme to The Third Man. “It’s funny, but when I remember back, or when I see films again years later, it seems that I remember them very much because of the music,” Barry later mused.

The piano, which he learned to play aged nine – hit by a stick across the hand when he got it wrong – was swapped for the trumpet by his teens. John’s brother, Pat, was into jazz and he followed suit. As their father got into promoting, his York cinema, the Rialto, became a showcase for visiting Americans including The Nat King Cole Trio, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Lionel Hampton and Duke Ellington.

At 15, Barry was already arranging music and was publicly championed by another of his visiting jazz heroes, Stan Kenton. Initiated by his father, Barry began to study intensively with Master of Music at York Minster, Francis Jackson, before getting expert tuition with trumpeter George Swift.

He moved on to play trumpet semi-professionally in local jazz band The Modernaires. Taking a correspondence course in music theory also enabled Barry to further write and test out early material on his bandmates.

National Service soon beckoned, and Barry found a prime posting as a musician with the British Army in Cyprus. He enjoyed this time, he said, as it gave him the chance to experiment musically, and learn how to lead a band with the “freedom to make mistakes”.

After a fruitful conscription, Barry was back in Blighty three years later, so he picked up arranging for the Jack Parnell and Ted Heath orchestras. By now, major change was in the air. The end of austerity was met head-on with the exuberant youthquake of American rock’n’roll. That new mood chimed with Barry. He set about acting on advice given to him by bandleader Parnell: “never be afraid to take the popular route”, resolving to form his own band.

After a fruitful conscription, Barry was back in Blighty three years later, so he picked up arranging for the Jack Parnell and Ted Heath orchestras. By now, major change was in the air. The end of austerity was met head-on with the exuberant youthquake of American rock’n’roll. That new mood chimed with Barry. He set about acting on advice given to him by bandleader Parnell: “never be afraid to take the popular route”, resolving to form his own band.

Shrewdly, Barry noticed that the new style of playing was more streamlined and therefore less costly to run than big bands. Momentous new music was a medium he could experiment with. Gathering together a mix of local musicians and ex-army colleagues, in 1957 he formed John Barry And The Seven.

Originally, the band comprised Barry on vocals and trumpet, drummer Ken Golder, lead guitarist Ken Richards, bassist Fred Kirk, and Keith Kelly on rhythm guitar, with Derek Myers on alto sax and Mike Cox on tenor sax.

Crucially, Barry’s father was able to offer the band their first professional gig, at the York Rialto. Meanwhile, they cut demos in London to send to TV’s exciting new ‘youth’ show Six-Five Special. Producer Jack Good, however, initially dismissed them as too similar to the regular show band, Don Lang & His Frantic Five.

As the Barry biography The Man With The Midas Touch explains, at least initially, “There were few role models available to aspiring rock’n’roll acts in the UK at the time. Every band invariably used Bill Haley’s sound as its blueprint.”

Undeterred, the group debuted on 17 March 1957. Things then moved fast: first, the offer of an ITV audition, and a prestigious summer season in Blackpool with Tommy Steele, fresh from the success of Britain’s first proto r’n’r hit, Rock With The Caveman.

The Seven proved so popular that the BBC promptly U-turned on Six-Five Special, though the station would now have to wait its turn. First up would be the band’s TV intro on Teddy Johnson’s The Music Box for ITV – plus an acclaimed concert appearance at London’s Royal Albert Hall. The Top 20 Hit Parade All-Star Show boasted the cream of 1957’s British pop talent, such as skiffle king Lonnie Donegan, who’d topped the charts with Cumberland Gap and Gamblin’ Man.

With package shows until then having been mainly variety based, the concept of The Top 20 Hit Parade was a novel one, and garnered much attention. The NME was quick to note that the John Barry Seven had taken London by storm, and likened their “exciting all-out beat music” to Freddie Bell And The Bellboys.

Appearing finally on the Beeb’s Six-Five Special in late September, the band played Barry original We All Love To Rock, plus Every Which Way – later their second single. Though Barry obliged with vocals, his naturally gruff Yorkshire tones were never a strong point. It took two EMI Parlophone singles to shift the focus to strictly instrumental numbers.

The first record release was a cover of a recent Diamonds B-side, Zip Zip, backed with Three Little Fishes; the second, Every Which Way b/w You’ve Gotta Way, had both sides featured in the subsequent film version of Six-Five Special. Backing Canadian teen sensation Paul Anka that winter concluded a whirlwind breakthrough year.

During 1957 and 1958, the JB7 were TV regulars on Oh Boy! – both in their own right and backing name acts. However, cracks in the line-up began to appear. Juggling a tough touring schedule with recording commitments made issues simmer.

Apart from original member Keith Kelly, one by one the band broke up. At the eleventh hour, a new, improved combo were ready for their own stage show, as well as supporting several other artists, including Marty Wilde, for a gig at the Metropolitan on Edgware Road in November 1958.

This new, sharp-as-their-suits line-up now boasted Barry on trumpet; Dougie Wright, drums; Vic Flick, lead guitar; Mike Peters, bass guitar; Keith Kelly, rhythm guitar; Jimmy Stead, baritone sax; and Dennis King on tenor sax.

By the time the band were approached to audition for the new Oh Boy! music show rival Drumbeat, Barry brought in Vic Flick’s pianist flatmate Les Reed as a replacement for the departing Keith Kelly (Barry introduced with Reed an innovative electric piano, produced by crudely amplifying an acoustic piano and attaching a block of wood to its underside, through which a wire was threaded into a speaker).

At this point, the band’s sound was truly unique, capitalising on the golden age of the guitar instrumental. They had become one of the top acts in the country, second only to The Shadows. The ‘classic’ line-up lasted until 1961, when Barry grew too busy arranging and composing to continue. He put forward Bobby Carr to take his place and Vic Flick as leader, under whose direction the Seven went on to enjoy further success in the UK singles chart.

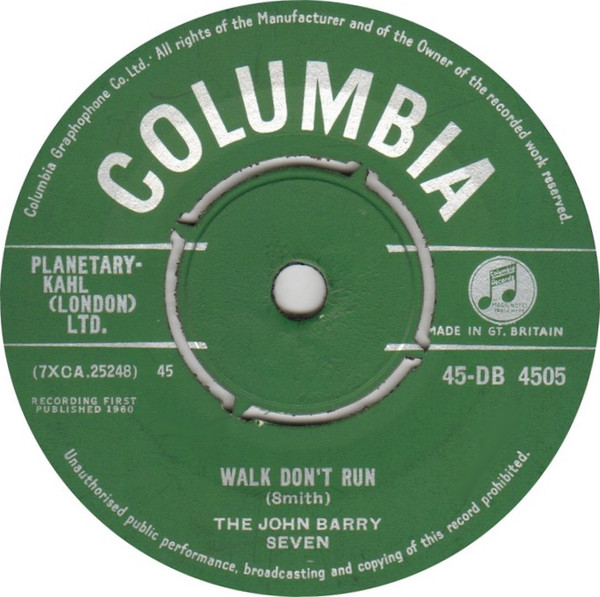

It had taken until the end of 1958 – Duane Eddy’s Rebel Rouser – for teenagers to be taken seriously, and for rock’n’roll in Britain to garner chart success. Only in 1960 did Barry and his band begin to have hits. Their Columbia debut Hit And Miss, the catchy theme tune Barry composed for TV’s seminal Juke Box Jury show, kicked off the new era.

A cover of the Johnny Smith song Walk Don’t Run, and Flick’s inspired, guitar-licking cover of the western The Magnificent Seven soon followed. Barry was also busy moonlighting as Johnny Prendry and arranging songs for other acts such as young Decca trio, The Barry Sisters (no relation).

From 1959-62, he was employed by EMI arranging orchestral accompaniments for the company’s artists and mentoring upcoming sensation Adam Faith. “Of all the people involved in my career, he was the most significant,” Faith later observed.

His musical style was totally moulded by Barry and the result was 12 Top 20 entries in three years. Barry arranged Faith’s first No.1, What Do You Want?, with its pizzicato strings in the style of Buddy Holly’s

It Doesn’t Matter Anymore. Amidst the material written for Faith, Barry also penned his first score: 1960’s flick Beat Girl.

At 29, John Barry was already a veteran of ‘va voom’ tracks with high production values. He had also perfected his own distinct, heavily reverbed, twangy trademark sound: ‘stringbeat’. The term became the title of Barry’s debut solo LP in 1961 – a daring showcase of 15 original tracks. Surprisingly, only one – Starfire, imminently the theme tune of ITV pop show Discs A Go-Go, was issued as a single.

In an ensuing research trip to the States to visit Capitol Tower and sit in on a Duane Eddy session, Barry learned two useful concepts: the multiple close mic’ing of individual instruments, and the value of separately recording performers in a practice now known as multitracking.

In 1962, Barry decamped to Ember Records, where he produced and arranged additions to the house catalogue. His talent was soon procured by the James Bond film producers. Hired as back-up to original composer Monty Norman, Barry was required to give Norman’s work a significant revamp. The end result, the James Bond Theme, was pure and enduring alchemy. By way of be-bop, it referenced the big, brassy Peter Gunn-style of rock’n’roll – but was more thrilling, modern, hip, and knowing. It was Bond, James Bond.

As for its emblematic licks, Vic Flick recalls using an f-hole Clifford Essex acoustic guitar with a DeArmond pickup, plugged into his Fender Vibrolux amplifier. “Over the next five years… my work with John Barry brought so much prominence on a string of his hit records with my lead guitar, leadership of his group out on the road and, best of all, a place in both record and movie history as the man who played the James Bond Theme,” he later recalled.

Barry’s career scoring movies, meanwhile, went from strength to strength – across 11 Bond scores and far beyond. He immediately took on From Russia With Love (1963), composed an alternative action theme entitled 007, and created his personal favourite of the franchise, 1964’s Goldfinger. The soundtrack album replaced The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night at the top of the US charts, was Grammy-nominated and scooped the composer his first gold disc.

It heralded a diverse, award-winning body of work for Barry, spanning from Born Free and Midnight Cowboy to Out Of Africa and Dances With Wolves.

Though his musical mojo had evolved, Barry was not averse to revisiting 50s sounds and rocking riffs: notably on his moody theme to The Persuaders, the cult 1971 TV series starring Tony Curtis and that sometime 70s Bond, Roger Moore.

Inducted into the Songwriters Hall Of Fame in 1998, he was awarded an OBE for services to music the following year. Married four times, Barry moved to the United States in 1975, where he remained until his death in 2011, aged 77.

When it comes to making memorable music – whether more contemporary seminal soundtracks, or his early innovative rock’n’roll – John Barry will be remembered for a towering legacy, which saw him become, as his Bond musical successor David Arnold put it, “the Guvnor”.