His contemporaries believed Dickie Pride possessed one of the finest voices of his generation, yet he died in obscurity aged just 27…

Janis Joplin, Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain… All members, sadly, of rock’n’roll’s ‘27 Club’, that list of artists whose light was extinguished at the tragically early age of 27. But there’s another name that predates them all, a singer who, at one point, looked as though he was on course to become one of the biggest acts in the UK, but whose death in the end barely registered on the media Richter scale.

Of all the artists in impresario Larry Parnes’ stable of male pop stars, Dickie Pride is the one who is, in 2021, hardly remembered at all. Yet he’s the one many of the bigger names on Parnes’ roster believed was the best singer of the lot of them. “We all thought that,” says Vince Eager, who worked alongside Pride in the late 50s. “And that was across the board.”

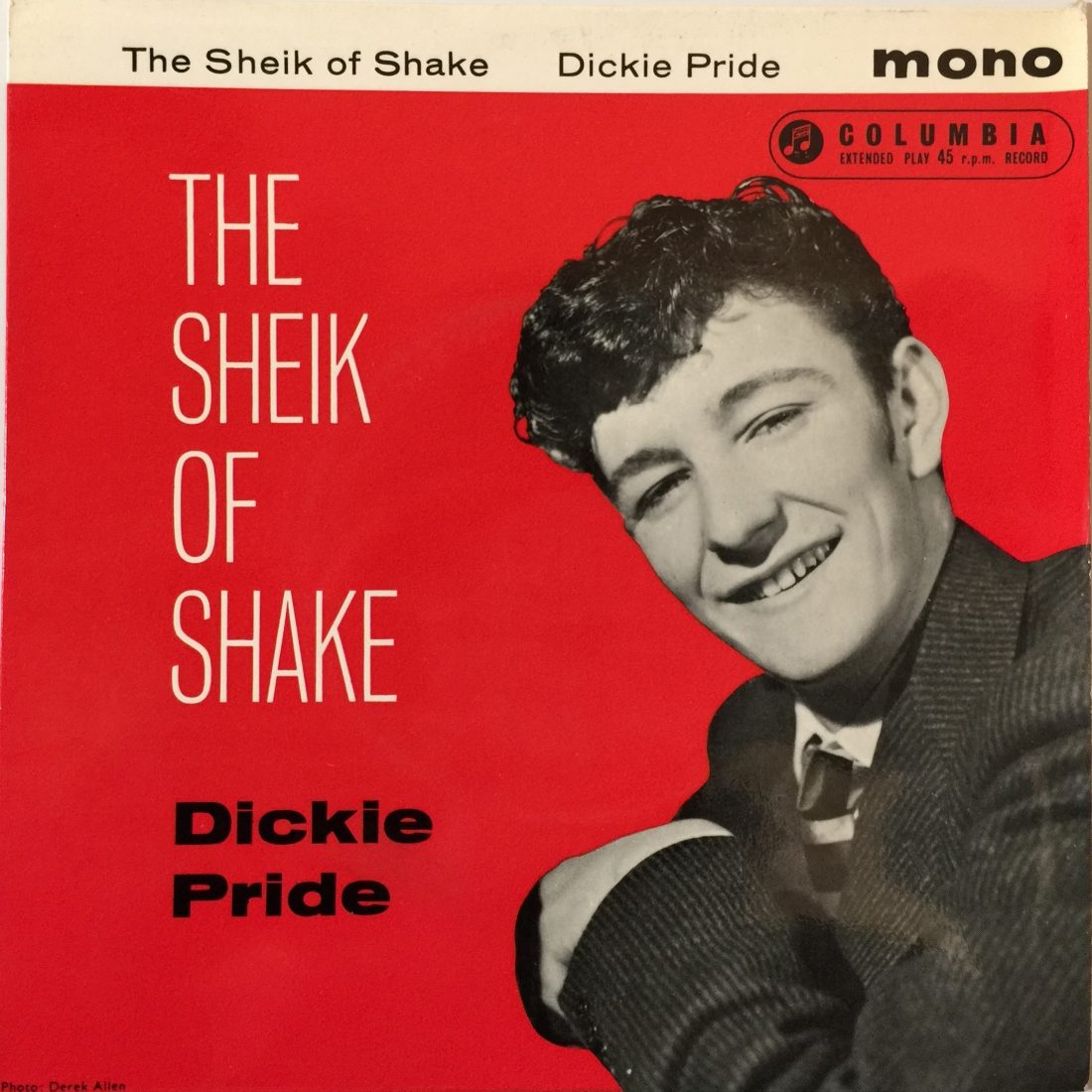

Dickie Pride would have turned 80 in October 2021. Yet the man born Richard Charles Kneller in Croydon in 1941 wouldn’t even see his 30th birthday, let alone his 80th, and would never become the all-conquering singing sensation many believed he’d be. But despite his lack of commercial success, for those in the know, there remains something deeply cherishable about the singer once nicknamed ‘The Sheik Of Shake’.

“What he ought to be remembered for,” said the author Charles Langley who penned the play Pride With Prejudice about Dickie in 1999, “is for his extraordinary talent, his scorching stage performances and the marvellous voice that brought other singers, and even the stage hands, running into the wings to watch.”

The one Dickie Pride number most fans of 50s and 60s rock and pop are likely to recognise is Primrose Lane, a chirpy reworking of country artist Jerry Wallace’s US hit from earlier in 1959. It had been cherry-picked as a single by Parnes and producer Norrie Paramor, but it was always an ill fit with Pride’s natural talent for ballads and the song stalled at No.28. It was to be Dickie’s first and only chart entry.

“The trouble was,” remembers Eager, “he really wanted to be more of, not a jazz singer so much, but along those lines. Just more of a serious performer and not a pop singer.”

Yet a pop singer was exactly what Larry Parnes was moulding Pride to be. Parnes had first checked out the then-17-year-old after Russ Conway had taken him to see Dickie perform at the Castle pub in Tooting in November 1958.

Conway had been blown away by the frail-looking crooner with the powerhouse voice and immediately got on the phone to Parnes, who signed Kneller, as he was then, on the spot. It was Parnes who re-monikered him as Dickie Pride, in his time-honoured tradition of giving his artists memorable, if sometimes cheesily dramatic names.

Dickie’s first single, released in March 1959, was a fiery cover of Little Richard’s Slippin’ ’n’ Slidin’. To Parnes’ surprise, it was shunned by the record-buying public, a fate that also befell Dickie’s other 7″s, Fabulous Cure (June 1959), Betty Betty (Go Steady With Me) (January 1960) and Bye Bye Blackbird (April 1960).

For Parnes, who prided himself on his ability to spot and nurture talent, it was baffling that Dickie’s records weren’t shifting. Not only did Pride have a voice that even his contemporaries were jealous of, but he had a starring role each week in one of the hippest TV shows of the time, Jack Good’s Oh Boy!

He’d made his debut on the programme in February ’59 and he’s there in one of the show’s most repeated clips. We all remember that sequence of Cliff Richard and Marty Wilde cooing Three Cool Cats, both looking impossibly young and swoonsome, so much so that it’s often easy not to notice the guy on the right of the frame.

The only one of the three never to enjoy chart success, it’s a harsh truth that, unlike Cliff or Marty, Dickie didn’t look like a star. Short and scrawny, it was never on the cards that he would become a heartthrob in the same vein as many of Parnes’ other artists.

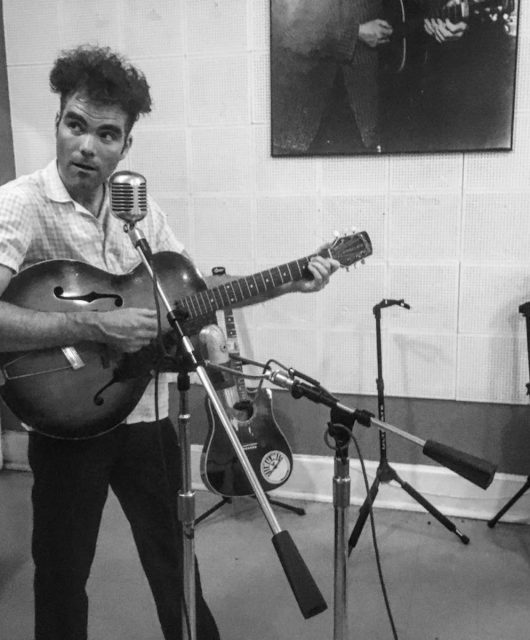

Which is likely why he developed his signature shaking performance (in fact, cribbed from Rory Blackwell of Rory Blackwell and The Blackjacks), a theatrical tremble that led to him being dubbed “the Sheik of Shake”. If people weren’t likely to talk about his face or physique, they sure as hell were going to remember the way he quivered on stage.

Despite his slender frame, however, Dickie was no pushover. “A pocket battleship” is how Georgie Fame once described him, and certainly there are many stories of Pride’s volatile temper getting him into trouble. One time, at Southend Odeon, he faced a particularly hostile audience and responded to the taunts by threatening to fight the entire crowd. “Right, I’ll see you all outside after the show,” he growled. “Then we’ll sort it out!”

“Obviously, no one was there when we went out the stage door,” remembered Tornados drummer Clem Cattini, “but he was prepared to take the whole world on.”

There’s another story of Pride drinking in a Birmingham pub with his stage make-up still on. When a local Ted whispered the word ‘poofter’ as he strolled past, Dickie turned around and belted him.

After he finished the performance that night there were, in Fame’s words, “about 200 Teddy boys outside the stage door, screaming for blood.”

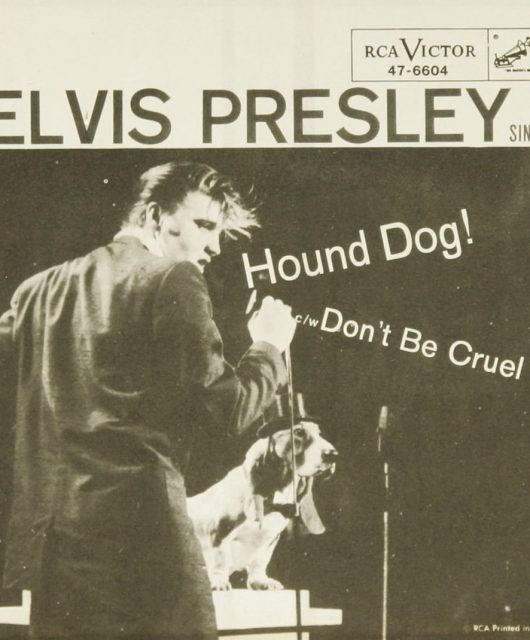

Yet, for all his rebel spirit, Dickie was always more of an old-time balladeer than a rock’n’roller. Though he’d started off in a skiffle band, The Semi-Tones, at home he listened more to 30s and 40s jazz standards than anything by Elvis or Little Richard. The trouble was, for the first year that Dickie was with Parnes, he was being packaged as something he wasn’t.

All that changed, however, in 1960. A resurgence of interest in trad jazz that year led Parnes, with typical alacrity, to jump on the bandwagon, putting on a show, The Big New Rock’n’Trad Spectacular, in December. It gave Dickie the opportunity to perform the kind of songs he wanted and led to a full album of jazz and Tin Pan Alley standards, titled Pride Without Prejudice. The record flopped, however, and Parnes, believing that there were no more avenues open to Dickie, dumped him.

The years after Pride left the Parnes stable were hard and often bleak. Though he married in 1962 and had a child, Ricky, in 1964, the relationship was marred by the couple’s excessive drug use and they separated a few years later, with his wife, Patricia, taking their son with her.

Despite being devastated by the loss of his family, Dickie was still dabbling in music, though he was forced to take a job as a van driver in order to bring in the cash. He started a few bands, first The Guv’nors and then The Sidewinders, a soul-influenced outfit that Little Stevie Wonder used as his backing band on his first European tour.

Throughout this time, however, Dickie was in the grip of an ever-worsening heroin habit. Despite The Sidewinders’ modest success, the band eventually petered out and Dickie, realising how bad his addiction had become, returned home to live with his mother and sister in 1968.

After Pride arrived back in Croydon, his family, shocked at the dire state of his health, admitted him to hospital. In the mid-60s, when there were just under 600 registered addicts in the UK, little was understood about heroin addiction.

Doctors theorised that his condition was a result of his depressive personality and recommended a lobotomy, a brutal medical procedure that, certainly by the late 60s, was fast going out of fashion. That said, it appeared to work, according to those who knew him at the time, with his sister remembering 30 years later: “You could see the old Richard there, coming through again instead of this awful manic depressiveness that he’d had. He was beginning to be more like himself.”

For the next year, Dickie regained a degree of control over his life. He secured himself a job and his appearance, which had been ravaged by the drugs, slowly improved. But without therapy, there was always a danger that he would drift back into the drug world, and eventually he started to gravitate to the jazz clubs that had introduced him to heroin in the first place.

One night, meeting up with an old acquaintance, he scored for the first time since before his operation. After

taking the bus home to Croydon, he topped up the heroin with a dose of methadone and went to bed. Waking up a few hours later, he downed a quantity of barbiturates, and then went back to sleep for the last time. His sister discovered him dead the next morning.

Despite his one-time fame, there was barely any newspaper coverage of Pride’s death that morning of 27 March 1969, and for much of the next few decades Dickie Pride was very much the forgotten man of late-50s and early-60s pop. Thirty years after his death, however, playwright Charles Langley authored his play about Dickie’s rise and fall and the BBC screened a documentary about the singer in their Jukebox Heroes series. In 2013, Peaksoft released a CD, The Complete Dickie Pride, which goes some way towards commemorating this breathtakingly versatile talent.

“He was a genius in my opinion,” remembered Larry Parnes’ road manager Hal Carter before his death in 2004, “but with a couple of flakes missing. God rest his soul, [he] was possibly the best vocalist and musician of the lot.