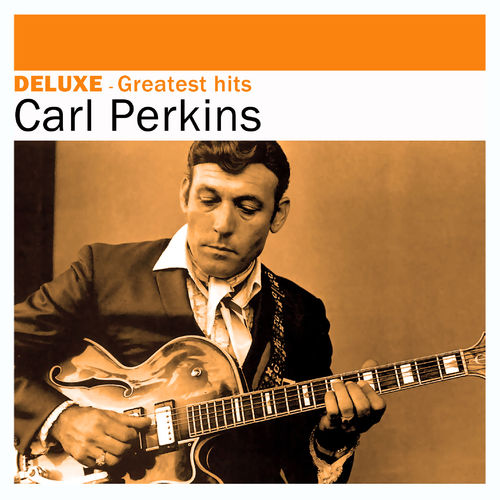

As much a country performer as a rockabilly one, Carl Perkins’ music is one that true rock’n’roll fans continue to cherish, even if his fame never quite soared like that of his contemporaries. With insights from Brian Smith, a former president of one of his British fan clubs, Vintage Rock looks at the Rockin’ Guitar Man’s post-Sun-era career… By Jack Watkins

Carl Perkins was the first rock’n’roll singer there ever was, even before Bill Haley,” said Gene Vincent in a late interview. “Even Elvis will admit it if you ask him. Bill Haley will admit it as well, and if it hadn’t been for that crash when he wrecked his back, Carl Perkins would have been the biggest rock’n’roll singer ever.”

Strictly speaking, the earliest, previously unreleased, recordings made before the artist joined Sun in 1954 on the new vinyl LP from Bear Family, Discovering Carl Perkins – Eastview, Tennessee 1952-53, don’t entirely reinforce Vincent’s argument.

They actually confirm him as an authentic country performer whose vocalising was underpinned by a keen and soulful sense of the blues, or as he would have put it, “blues with a country beat.” His Good Rockin’ Tonight, possibly cut a year or two before Elvis Presley got to work on his version for Sun, is delivered as a swinging, churchified country blues boogie.

He sings Eddy Arnold’s There’s Been A Change In Me and his rough, lazy drawl seems closer to Jimmie Rodgers than the smoother, more finished style of Arnold (an effect maybe exaggerated by the primitive recording). Among the other tracks on the 10“ disc are rare outtakes from Perkins’ earliest Sun days.

It’s the raw energy of these, especially the cherished Gone, Gone, Gone, that remind the listener of his talents as one of the most elemental of the early rockers, who had long claimed that he’d been performing rock’n’roll before he heard the Hillbilly Cat was doing the same.

Perkins has always been a purist’s favourite, and his inventiveness as one of the definitive rockabilly guitarists made him something of a musician’s musician. But there’s a sense that, more widely, the Rockin’ Guitar Man has been slightly written off as a one-hit wonder.

The crash that Vincent referred to frustrated his ability to capitalise on the million-selling crossover success of Blue Suede Shoes in 1956. By 1958, disillusioned by Sam Phillips devoting more resources to selling other artists on the Sun roster like Jerry Lee Lewis, he joined Columbia Records.

The general verdict is that he never again cut anything to match the best of his Sun era output. The first of two stints with Columbia lasted until 1963. It coincided with a dark period in his life. The loss of his brother, Jay Perkins, a member of the Perkins Brothers band since the earliest days, to a brain tumour in 1958, hastened a descent into alcoholism, abetted by falling record sales. But while most pundits have pointed to a loss of the exciting experimental energy of his Sun output, there are plenty of his later recordings that have stood the test of time.

Only two of his Columbia singles, Pink Pedal Pushers, a song he’d originally experimented with at Sun, and Pointed

Toe Shoes, scraped into the pop charts. Both were penned by the artist and it showed. Much of his Columbia material was written for him, and gone was the attacking guitar. On Levi Jacket (And A Long Tail Shirt) a saxophone handled the instrumental break.

Perkins would later say that the skill of Nashville session men intimidated him and quietened him down. What’s plain from these recordings is that when he was being himself and feeling the material, he was interesting. When he tried to toe the commercial Nashville line, he sounded ordinary.

But this doesn’t mean all the sides Perkins cut for Columbia are forgettable. This Life I Live showed what a great R&B singer he was. Sam Cooke in his Soul Stirrers’ era wouldn’t have disowned the rasping climax to Highway Of Love. Y-O-U was a tender ballad typical of the period that Presley couldn’t have sung better. I Don’t See Me In Your Eyes Anymore showed that, like Johnny Burnette, he excelled on a certain type of yearning country ballad.

On The Fool I Used To Be he captured something of the feel of another ex-Sun man, Charlie Rich, the most soulful of the early rockers. The ripe maturity in Perkins’ voice showed why his talent was wasted on that disc’s topside, the disposable Hollywood City.

There was also a Columbia album, Whole Lotta Shakin’. On the face of it, what could be more tedious than a long-player of familiar songs only recently done to perfection by the likes of Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard? Yet Perkins roared his way through Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On, Shake, Rattle And Roll and Long Tall Sally with a raging power that was almost frightening.

In his second Columbia period at the end of the 1960s and when he came to London to appear at the Wembley International Festival Of Country Music in 1981, Perkins sometimes seemed too much the laid-back good ol’ boy. But Whole Lotta Shakin’ showed that, at his best, he never conceded an inch to anyone in the flat-out rockin’ stakes.

All the same, Perkins’ fortunes were at a low ebb by the time Columbia decided not to renew his contract. He hopped over to the Decca label, but when that brought no upturn in fortunes, contemplated getting out of the music business altogether.

That idea was ditched when he was offered the chance to join Chuck Berry on a first ever UK tour in 1964. Perkins had enjoyed just one British hit, the inevitable Blue Suede Shoes, but Dance Album Of Carl Perkins

had been released here and, unbeknown to him, he had still retained a small, but enthusiastic following, and the shows were well received.

Perkins admitted he was in total shock at the way the concerts were sell-outs, with “the kids bopping in the aisles”. Less fortunate were the Merseybeat band The Swinging Blue Jeans and The Animals, who opened the shows and were subjected to boos and jeers from hardcore rock fans. The Nashville Teens, who backed Perkins, fared better.

In fact, they got on so well with Perkins, he recorded a single with them while in the UK, comprised of two Perkins originals. Lonely Heart was backed by the superior Big Bad Blues, the latter an apparent attempt to reactivate the sound of his Memphis-era pomp. But the rushed UK-only release on Brunswick made no impression on the charts.

Not only had American records been hard to obtain in the UK in this period, information on rock’n’roll stars was also scarce. Fans networked through local clubs, one of which was the Twisted Wheel in Manchester. Among its regular attendees was Brian Smith, whose hobby was taking photos of the stars in concert and, if he got lucky, backstage.

These ran the gamut of blues, R&B and Big Beat performers, everyone from T-Bone Walker to Bill Haley. He had no intention of missing out on Berry and Perkins in 1964.

“I already had a couple of Perkins’ records, but he’d been off the scene for a while. However, when he came over on that first Berry tour, he was wonderful. He was such a nice bloke and me and a few friends went round to several shows. Chuck Berry was nice to us as well, for that matter. This was before he got his reputation for being a badass. Chuck was always great with us, so long as you stayed in your place. But Carl was so friendly, me and my friend Dave Waggott got quite pally with him.

“He said, ‘It’s a shame there’s no proper fan club’, so we ended up getting him to sign this note authorising me and Dave to act on his behalf. Dave was an artist and he did this illustration of Carl which he also kindly signed for us. I lost touch with Dave years ago, but was searching online a few years back, and remarkably someone had posted Carl’s authorisation of the fan club and Dave’s picture of him. It’s on the wall of the Hard Rock Café in Memphis, and I’ve absolutely no idea how it got there.”

As club president, Brian took his duties very seriously. “To get the club started we had the bright idea of getting 50 matchboxes, which Carl signed for us, to be sent out to the first 50 members. All went well, except when our first ad went in Record Mirror. Beside it were two more advertising their own Perkins fan clubs. Other British fans had obviously had the same idea! One of them was “Breathless Dan” Coffey who’d already established his news fanzine. So for the next two years there was this embarrassingly acrimonious stand-off between us. I cringe at some of the stuff I wrote, but eventually we merged with Dan under the Boppin’ News banner.”

An indication of how the early British beat scene had drawn inspiration from the early rockabillies was the way The Beatles had lapped up Perkins’ recordings. Famously, at a party at the tour’s end, the young men got an audience with their idol. Perkins hadn’t thought much of what he’d heard of The Beatles up to that point, he admitted in an interview in Rolling Stone with David McGhee, who also helped him write his autobiography, Go, Cat, Go!. “I’d say, ‘Those damn boys look like girls. They ain’t no good,’” he admitted to McGee. The fact that George Harrison had already gone public in homage to his genius cut no ice.

“I said, ‘I don’t care what he said. They’re sissies.’ I was jokin’, but deep down inside kind of meant it a little bit. But I did hear some raw Sun Records sounds in those guys.” At the party, however, Perkins was so disarmed by John Lennon’s enthusiastic questioning that he gave the nod to them doing some of his songs at a recording session at Abbey Road, including Matchbox and Honey Don’t. “Help yourself , the catalogue’s yours,” he said, later admitting he’d seen dollar signs ringing up before his eyes.

But the boost to his battered morale of that Berry tour had been enormous. “When I got on the airplane the next day,” he told McGhee, “I knew I had a place that loved me and my music. I had begun to feel in America that it was over… But I came back, and I was more determined. Right after is when I joined Johnny Cash. England was alive for me; they never forgot me.”

Perkins joined the Cash roadshow in 1965 as a featured artist, gaining further exposure on Cash’s networked TV show. In 1968, Cash toured Britain twice, bringing with him his new wife June Carter, along with Perkins. The first of these tours had required Perkins to step in as Cash’s guitarist when longstanding Tennessee Three linchpin Luther Perkins had been taken ill and gone back to the States.

By the time Cash was back for the second tour later that year Luther was dead, killed in a fire. Renewing his acquaintance with his old friend backstage at the Manchester Odeon, Brian Smith recalls Perkins confessing that he’d struggled to replicate Luther’s famously basic style. By now Cash had brought in Bob Wootton as a permanent replacement, and Perkins reckoned this accomplished guitarist would face the same temptation to over-elaborate.

The Cash-Perkins association also endured for several years. Perkins wrote Daddy Sang Bass for Cash, which gave the singer a country chart No.1 in 1968. Perkins reckoned it was one of the best songs he ever wrote. The pair, who helped each other with their drink and drugs problems, often wrote music together, including for the movie Little Fauss And Big Halsy.

In Britain in 1973, again as part of the Cash touring troupe, Brian Smith recalled Perkins coming without medication for his ulcer. “So I’d spend time going round the chemists getting stuff for him. My mum was always a bit ambivalent about Carl Perkins and me constantly going off to see him, which she thought was bit odd. But she did like Johnny Cash. So as their wedding anniversary was coming up, I took my mum and dad to see one of the shows, mentioning it to Carl beforehand.

So in the middle of the show Carl gets out this slip of paper and reads, “This next song is for Brian Smith, who’s here helping his folks celebrate their wedding anniversary tonight.” Oh, after that, Carl Perkins could do no wrong as far as my mum was concerned. I have to say I thought his choice of song was a bit strange though, because it was One More Loser Going Home.

“The last time I saw him was a fabulous show he performed in Wellingborough, in November 1994. When we heard he had throat cancer we thought that was that. But he came back and was really good that night, and we thought he’d got over it, although it obviously caught up with him. Anyhow, we had a big reunion at the show. I’d been showing him pictures of my four kids. He followed me out into the car park, and said, ‘Can you give me some of those pics, I’d like to show them to Val [his wife] when I get home.’ So that was Perkins the family man.”

Touched as Brian was, the sweet and simple gesture now sounds like a parting shot to Britain, though he’d be back for one last show at the Royal Albert Hall in 1997. Because Carl Perkins never forgot the British music lovers who’d given his career that tremendous shot in the arm when it all looked over in 1964, never lost a sense of gratitude for what they had done.

Not for the first or last time, an American artist, almost entirely neglected in his homeland, has resuscitated his career by flying into a cloudy, rainy island across the Atlantic to meet people whose heartfelt appreciation reasserted his place in the pantheon of the greatest early rockabillies. ς