The final two movies of Elvis’ silver-screen career saw him jump outside the Hollywood system and return to what he did best – thrilling the crowds on stage as a live performer… Steve Harnell examines the films Elvis: That’s The Way It Is and Elvis On Tour…

If you want to experience the essence of rock’n’roll, there’s no substitute to getting down and dirty – the visceral thrill of the live show is where it’s at.

That goes for performers as well as audiences. The Beatles may have prospered artistically when they became a studio-only band, but they’re almost unique in that respect. Every other major artist from Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis through to The Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin and The Who cemented their legacy with years of getting sweaty with their fans.

Early in his career, Elvis was no different. His live performing style was as important as his studio work as he made waves around the world. That nervous perma-shaking leg, the trademark lip curl and those wickedly mischievous blue eyes, it all fed into making him a rock’n’roll sensation.

When Colonel Tom Parker threw Elvis into the Hollywood machine for a catalogue of exploitation moves throughout the 60s it was a cynical move to extract the maximum amount of cash from Presley’s global brand. On the one hand it made sense, it was much easier to knock off a quick movie and export that across the world than it was for Elvis to play everywhere in person. And of course Parker’s motivations for keeping his charge on home soil were also prompted by the fact that travelling outside the US would be impossible for Parker – born in Holland, he gained entry to the States illegally by jumping ship at the age of 18 and never owned a passport.

But the Colonel’s decision removed Elvis from his fans, putting him at an untouchable distance on the big screen. Save for a handful of dates in 1960 and ’61, Elvis would not set foot on stage for a full show until his hotly anticipated comeback at the International Hotel in Las Vegas on 31 July 1969.

The original impetus for a return to live work came from Presley himself; he told the Colonel about his desire to return to gigging while backstage at NBC’s Burbank studios following the taping of what became the ’68 Comeback Special. The ecstatic reaction of the crowd lit a fire under Presley that had lain dormant during his Hollywood years.

Parker set to work on crafting a plan and immediately targeted Las Vegas as the key location to launch Presley’s ‘Second Coming’. It seemed perfect on two fronts; firstly, it allowed both star and mentor to settle an old score. Presley’s last performances in Vegas back in April and May of 1956 were greeted by an uncharacteristic shrug from audiences, a rare failure by the star in an otherwise unimpeachable rise to fame. Crowds more used to the likes of Sinatra and Peggy Lee couldn’t get to grips with the primal energy of a visceral Presley.

This time, though, Parker knew things would be different. The music world had moved on and Elvis possessed the kind of gravitas that few of his peers could match as well as an all-killer no-filler setlist. Conquering Vegas would also afford the Colonel more bargaining power when negotiating with other promoters elsewhere around the States.

The statistics for Presley’s grand return made for impressive reading. The newly-opened 30-storey International Hotel boasted a 2,000-capacity main room, double that of the type Sinatra and Dean Martin were playing at the time. At that point, it was the biggest hotel in the world, a grandiose statement that fitted the ‘Return Of The King’.

Playing two shows a night for a month, Presley scooped $400,000 for his efforts. The shows were a triumph, Elvis a bundle of nervous energy as he reconnected with his adoring fans.

A year later, Elvis returned to the International Hotel with a reconfigured line-up of musicians, now dubbed The TCB Band. Many of those were retained from the original line-up he put together for his 1969 Vegas shows.

Put together by producer Felton Jarvis, The TCB Band’s leader was guitarist James Burton, the hottest session player in Los Angeles, who’d cut his teeth as a teenage wunderkind on the Louisiana Hayride radio show before working with Dale Hawkins and Ricky Nelson.

With Elvis planning a wide-ranging melting pot of musical styles for his setlists, adaptability and virtuosity were key for his back-up players. Bassist Jerry Scheff came from a jazz and R&B background and had previously played on two Elvis movie soundtracks, Double Trouble and Easy Come, Easy Go, while much under-rated powerhouse drummer Ronnie Tutt was one of the most adaptable sticksmen in the business, able to change tempos on the fly by following a hand gesture, nod or leg movement from Presley up front.

Pianist Glen D. Hardin was also a talented arranger and helped define Presley’s sound in the new decade. Hardin was a perfect fit for the ambitious, swelling cover versions of tracks such as Bridge Over Troubled Water and You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me, as well as the original tracks such as The Wonder Of You.

Equally intrinsic to Presley’s expansive sound of the early 1970s would be the addition of two vocal groups as support, the white male gospel quartet The Imperials and black all-female pop and gospel outfit Sweet Inspirations. The groups would underline Presley’s southern roots and were at the very heart of his expansive, maximalist sonic approach.

Elvis had previously collaborated with The Imperials back in 1966 on a gospel session while The Sweet Inspirations had impressed him via their work with Aretha Franklin, Solomon Burke, Wilson Pickett and Van Morrison.

In fact, Presley was so enamoured by both groups’ work he hired them without the formality of an audition. The Sweet Inspirations had been initially reluctant to take the Vegas gig with Elvis, hesitant at making money in Sin City; they were only won over by how passionately engaged Presley was during rehearsals. Rounding out the sound was an orchestra led by musical director Joe Guercio. No expense was spared in making this the most full-on gig experience around.

Presley’s on-stage Vegas victories had prompted a sea change in the town, no longer was it solely the preserve of fusty middle-aged audiences sipping on shorts and eating dinner while they snoozed away at crooners and staid stand-up comics. Instead, Elvis’ high-octane show injected some youthful vigour into the town. Younger audiences were now flocking in their droves to see him – and splashing the cash in Vegas’ hotels and casinos.

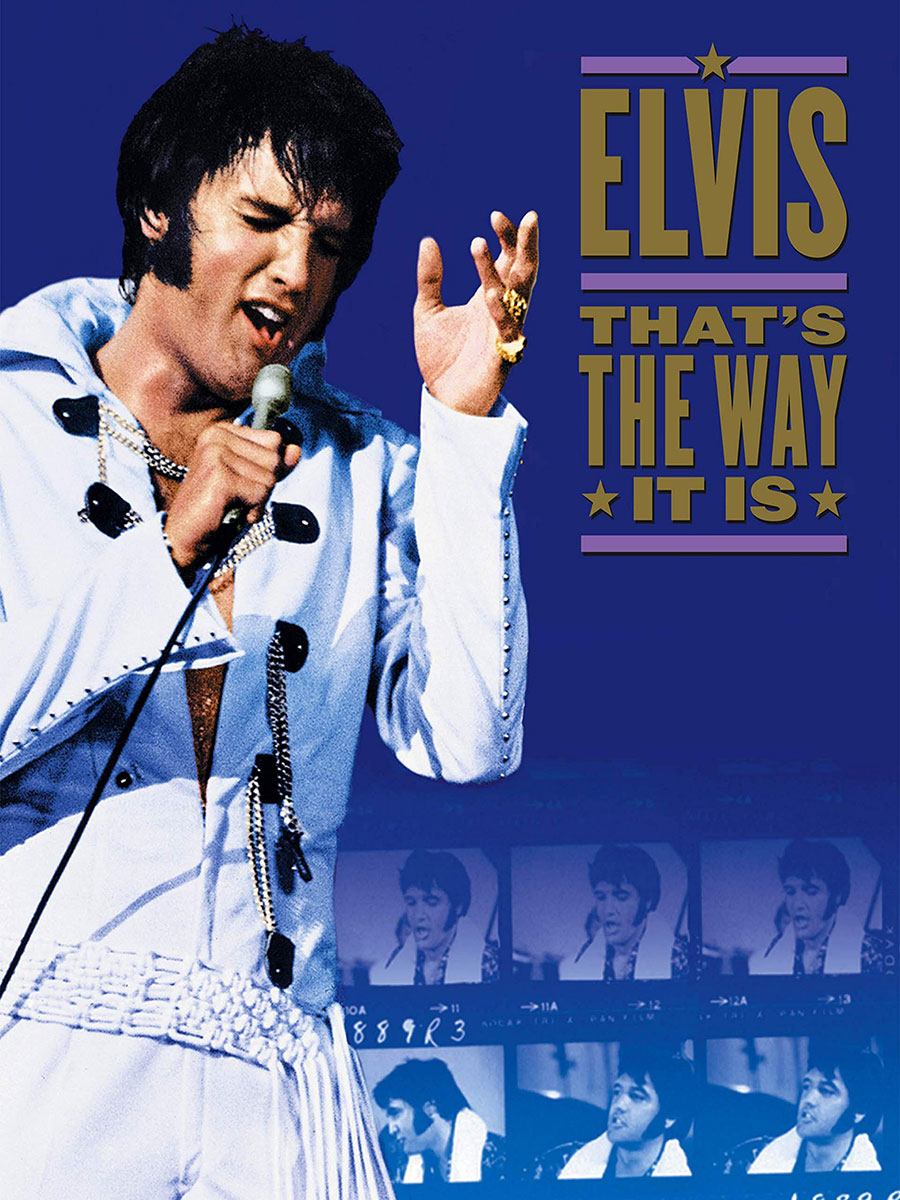

With the Elvis Vegas experience making headlines around the world, the time was right for a global audience to experience what all the fuss was about. A feature-length documentary, Elvis: That’s The Way It Is, would bring the Presley live show to cinemas around the world. Directed by Denis Sanders, it would mix rehearsal footage, and behind-the-scenes glimpses at Presley and his inner circle with excerpts from the various live shows recorded at the International Hotel in August 1970. As a coup for the documentary, the opening credits contained footage of a concert at the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum in Phoenix on 9 September 1970, Presley’s first tour show in 13 years.

“This documentary revealed the full force of his stage personality coming through the camera for the first time,” explained John Douglas Eames of MGM.

Elvis’ first non-dramatic role since making his big screen debut in Love Me Tender back in 1956, That’s The Way It Is utilised techniques of two previously critically-acclaimed documentaries. Although the experimental elements of Jean-Luc Godard’s Rolling Stones feature Sympathy For The Devil aka One Plus One were dispensed with – they hardly fitted with Presley’s across-the-board mainstream audience – its reportage-style scenes of Elvis rehearsing and larking around with his musicians and inner sanctum helped to humanise the singer. He was no longer the untouchable celluloid superhero, he was a working musician and one of the lads.

A split-screen technique cribbed from the Woodstock documentary (and also a feature of hip Hollywood movies including The Thomas Crown Affair, would bring the presentation of Elvis bang up to date. Eight Panavision cameras were used to ensure that no nuance of the performance, from either Elvis or his assembled musicians, would be missed. Cinematographer Lucien Ballard came with a heavyweight CV including Western masterpiece The Wild Bunch and utilised a similar short, sharp cutting style to intensify the excitement and momentum of the footage. Meanwhile, director Denis Sanders had previously won two Oscars for his 1954 short film A Time Out Of War.

The original concept for Elvis’ latest product was to a be a countrywide closed-circuit television presentation of a single show, but Parker walked away from a $1.1 million deal.

The eventual That’s The Way It Is would be far more involving. Gathering pace as it goes along, it begins with footage shot during five rehearsals at MGM studios in Culver City as Elvis worked up a repertoire of 60 songs to choose from for the shows – far more than a typical selection of 20 to 25. It’s instantly apparent that The TCB Band are a crack team of musicians, it’s dazzling how quickly they pick up You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me on the hoof. Equally, they’re at ease when a version of Little Sister morphs into a cover of The Beatles’ Get Back. Presley seems very much in control of the vocal arrangements, bursting with ideas as they’re tossed back and forth amongst his assembled musicians.

Showpiece songs in the final live set are equally enthralling, from the transformed version of Bridge Over Troubled Water, which switches up the delicacy of the original Simon And Garfunkel arrangement and morphs into a gut-wrenching epic. Equally bombastic is centrepiece song Words. While tenderness and subtlety were part of Elvis’ vocal armoury, the tendency with these live performances is to go for a bravura approach; slow-building epics ending in a powerful crescendo.

While nervous energy was a feature of early Elvis shows, his performance style by now was more commanding and exhibitionist, employing karate kicks and chops, air punches and much shaking of his acoustic guitar for dramatic effect.

Footage of Elvis reading backstage notes from well-wishers is intercut with star names assembled in the audience, from Cary Grant and Sammy Davis Jnr to the perma-tanned actor George Hamilton.

Apart from Elvis’ extraordinary vocal performances, an equal feature of the movie is the way he can be seen to be having fun with his material. See him mugging around with a tiny toy guitar before Love Me Tender. This was, by the way, more clean-cut Elvis banter – Colonel Parker had previously had to warn his charge the year before when between-song jokes began to wander down X-rated avenues.

The dynamic with the audience is key here. Witness how when Love Me Tender finally kicks in Elvis spends the majority of the song kissing females in the audience. And no polite pecks on the cheek, either. These were full-on open-mouthed passionate embraces.

It’s an extraordinary performance that underlines the success of Presley’s comeback. His early classics including Heartbreak Hotel now seem reborn, there’s a gravitas and maturity that was missing from the bare-bones originals.

Despite the typically Luddite Parker quibbling about the fast cutting style and informal banter included, That’s The Way It Is was a thoroughgoing success. It did decent business at the box office and, as Gene Siskel noted in the Chicago Tribune, it had one eye on Presley’s future live work, too, as he described the documentary as “a carefully managed […] concert designed to promote [Elvis’] future engagements in Nevada.” He noted that “fans will be enthralled as Presley sings more than a dozen of his hits” but that “persons hoping to learn about the man after hours will be disappointed.” That latter comment seemed rather harsh. This was, after all, much less stage-managed than previous Elvis big screen outings.

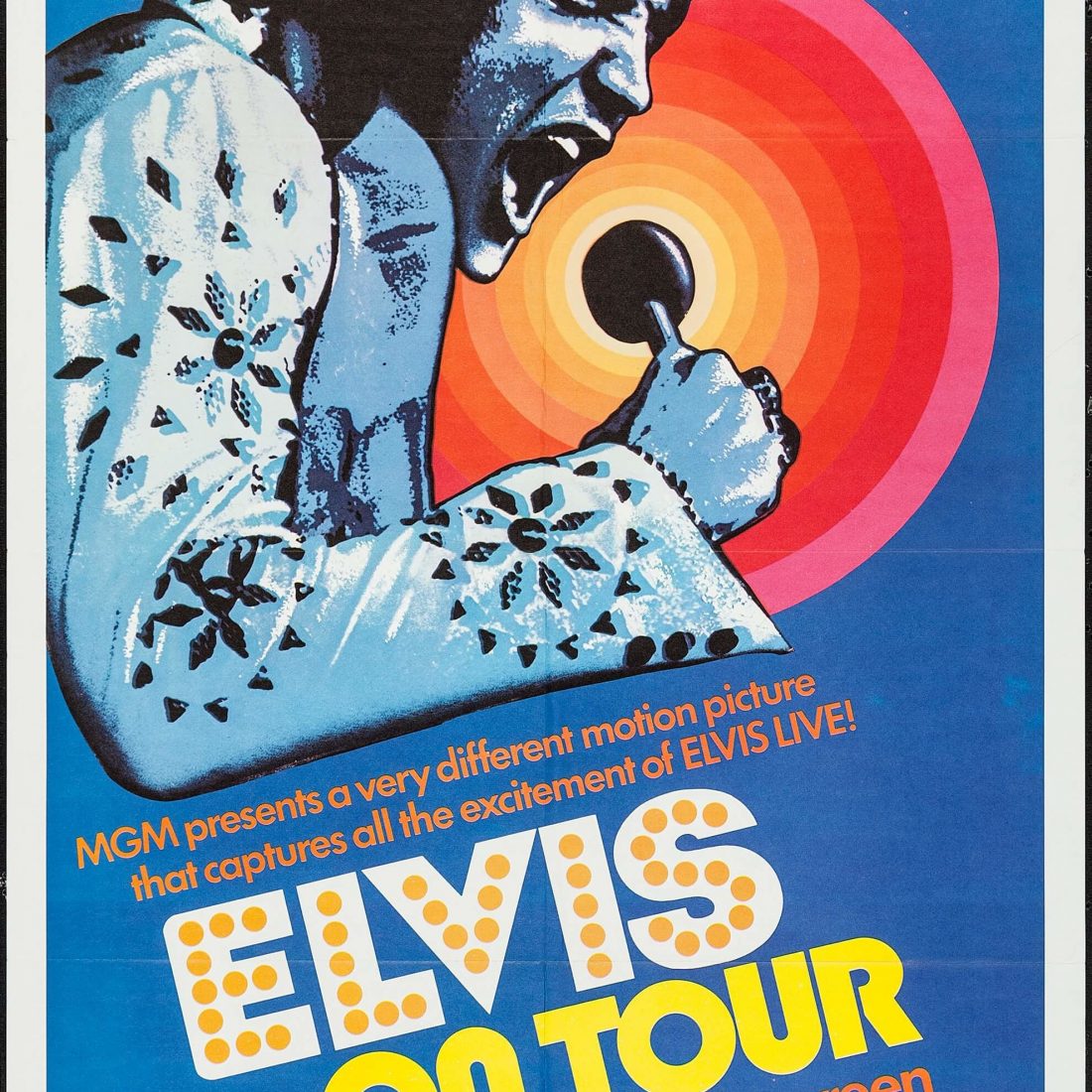

Two years later, Presley returned with his 33rd, and final, movie outing. Elvis On Tour followed the King on a 15-city jaunt around the US that encompassed 19 concerts between 5-19 April 1972.

It broadly retains the stylistic traits of That’s The Way It Is – pre-tour rehearsals are featured alongside selections from the stage performances interspersed with over-emotional fans wilting at even the thought of meeting their idol. Also included is vintage footage of Presley’s appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show back in 1956 where he played Don’t Be Cruel and Ready Teddy; a clear indication this was an artist with a rich history that reached back to the nascent days of rock’n’roll.

Dotted throughout the various footage are audio-only quotes from a 40-minute interview that Elvis provided to give an up-to-date perspective on proceedings. It opens with Presley musing on his earliest days: “My daddy had seen a lot of people who played guitars and stuff and didn’t work. So he told me, ‘you should make up your mind about either playing guitar or being an electrician. I never saw a guitar player that was worth a damn.’”

Thankfully, Elvis never took his father Vernon’s advice…

Like That’s The Way It Is, its follow-up retained the then-fashionable split-screen approach. Martin Scorsese, still a year away from directing the classic Mean Streets, supervised Elvis On Tour’s montage sequences, imbuing them with a similar snappy style that he brought to bear on the movie of the Woodstock festival that hit cinemas in the spring of 1970.

When we see our hero for the first time, he’s noticeably heavier than in That’s The Way It Is. Clearly the years of excess binge eating were just beginning to show on his face and around his waistline.

Four shows were utilised for the live footage; two concerts in Virginia – at the Hampton Coliseum and the Richmond Coliseum, a gig two days later at the Greensboro Coliseum in North Carolina, and a final fourth show at the Convention Center in San Antonio, Texas.

It’s textbook 70s Elvis pomp-era stuff. From the moment a soundalike for his now-traditional intro tape of Also Sprach Zarathustra begins (the original version couldn’t be used for copyright reasons), the band rip into a breakneck version of See See Rider, with the assembled musicians hanging on to Ronnie Tutt’s galloping backbeat for dear life.

Elvis himself looks iconic in his blue diamond-encrusted jumpsuit and a bejewelled garish belt.

Polk Salad Annie is an early highlight, featuring a muscular bassline from Jerry Scheff, and the busy arrangement of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s 1969 hit Proud Mary amps up the original to wonderful effect. Both songs, of course, were aimed at underlining Presley’s Southern roots.

It’s fascinating to see an early performance of Burning Love; Presley is so unfamiliar with the freshly-minted song that he has to read the lyrics on-stage from a sheet of paper.

As would become habitual for Elvis over the years, like Prince in the following decades, Presley’s singing was not just confined to the stage. After playing two shows a night, Elvis would often regroup with his backing singers to perform gospel songs until dawn.

A three-song gospel interlude (The Lighthouse, Lead Me, Guide Me and Bosom Of Abraham) are sung by Elvis with J.D. Sumner and The Stamps Quartet during an after-hours informal jam session. It’s a goosebump-inducing selection that also has the King shaking his head in disbelief at the beauty of it all.

There’s light and shade to be found elsewhere amongst the seriously great music. The producers, much to Colonel Parker’s chagrin, create a medley of Elvis’ big-screen kisses down the years to back the live version of Love Me Tender, a tongue-in-cheek (ahem) dig at the repetitiveness of Presley’s Hollywood years that Parker took offence to. Despite his protestations, the section stayed in the picture.

Also providing some light relief was a by-now traditional cavalcade of adoring Presley fans, weak at the knees at the prospect of their obsession coming to town. “My husband’s just had an operation but I wouldn’t miss this for nothin’!” avers one overcome housewife.

The movie’s centrepiece, like the shows themselves, is a tour de force performance of An American Trilogy, then like now an instant classic in the Presley repertoire.

Glen Hardin is on fine form on a rollicking A Big Hunk O’ Love and the bleak ballad You Gave Me A Mountain showcased the emotional depth that went hand in hand with 70s Elvis alongside the rock’n’roll thrills. A grandstand finish was provided with Presley and his band revisiting his classy Blue Hawaii ballad Can’t Help Falling In Love.

“Elvis has left the building” intones the PA announcer as the hubbub draws to a close. He had, but not before reasserting himself as the most potent live singer of his generation.