First generation British rock fans have never lost an affection for Buddy Holly, but the arrival of compilation double album Legend presented his genius to a younger audience in the mid-70s…

To be a music-loving teenager as the late 1970s ran into the 1980s was the best of times. The range of musical styles on offer was vast and exciting. As Simon Reynolds put it in his weighty, thought-provoking Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984, the period “rivals the 60s in terms of the sheer amount of music created, the spirit of adventure and idealism that informed it, and the way that the music seemed inextricably linked to the political and social turbulence of the times.”

Needless to say, Reynolds, who wasn’t massively enthusiastic about The Clash’s “anthemic rock’n’roll” and reckoning that most punk records sounded like they might have been recorded in the pre-stereo era, didn’t have anything to say about neo-rockabilly. Even if he had, he might well have agreed with the generally held view in the music weeklies of the day that it was stuck in a backward facing cul-de-sac.

But in this great era, there were some of us who reacted to music on a purely emotional level, going on how it sounded, rather than how innovative it was, or how likely to change the world. That was why revival acts such as Matchbox, The Jets and early Shakin’ Stevens were so appealing. Hearing The Polecats’ Marie Celeste for the first time was just as novel as falling in love with The Specials’ Gangsters or The Skids’ Into The Valley. There was also the increasing availability of reissues of original 1950s rock’n’roll, each sounding completely fresh and new to teenage ears.

Rock’n’Roll Revival

The first tremor of an authentic early rock mainstream breakthrough had been the reissue of Hank Mizell’s Jungle Rock on Charly in 1976. Although not originally a hit when released in 1958, it was well known on the thriving British underground scene and Shakin’ Stevens And The Sunsets had cut it as a single. While The Sunsets were a brilliant band, they enjoyed little luck and their offering had gone nowhere.

However, the original Hank Mizell cut, with its insanely infectious clanging guitar rhythm and atmospheric echo recorded in a Chicago garage, swept up the charts to No.3 in the UK in April ’76. Once heard never forgotten, from here the mono path was mapped out.

The joys of MacCurtis and Jack Scott lay in the glorious, unknown future, but for now it was all about early Elvis, Bill Haley, Gene Vincent and Jerry Lee Lewis, as well as being stunned by the rapid strumming on The Everly Brothers’ Claudette and Wake Up Little Susie. All of this sounded mint new and a total revelation.

And then there was Buddy Holly and Legend. On one level he was, of all the 50s acts, an artist who didn’t need rediscovery. Buddy had always been loved by an older generation of British rock music fans and, like Eddie Cochran, his memory was cherished more here than in his homeland.

Definitive Collection

Mike Berry And The Outlaws’ warmly nostalgic Tribute to Buddy Holly reached No.24 on the UK charts in 1961. Berry was still successfully mining his idol’s style a year later with the even bigger seller Don’t You Think It’s Time. The Hollies professed their love of Holly simply in their band’s name, and The Beatles referenced The Crickets in theirs. The Teds went on revering the star, and early British rockabilly revival bands such as Wild Angels, The Hellraisers and The Sunsets were expected to include his songs in their sets.

Despite scoring hits with Oh Boy and Heartbeat in 1975, Mud and Showaddywaddy’s glam-flavoured interpretations didn’t have many youngsters scurrying away to check out the originals. But, soon things were about to change.

Released in 1978, Buddy Holly Lives: 20 Golden Greats took Holly to the summit of the UK album charts, selling over 300,000 copies. This was around the time the biopic The Buddy Holly Story hit cinema screens. Reviewing the album in the NME, Charles Shaar Murray rated Holly as one of 50s rock’s “three incomparable all-rounders equally adept and influential as singers, composers and guitarists,” with the others being Chuck Berry and Eddie Cochran. But the definitive Buddy Holly collection, he noted, was Legend.

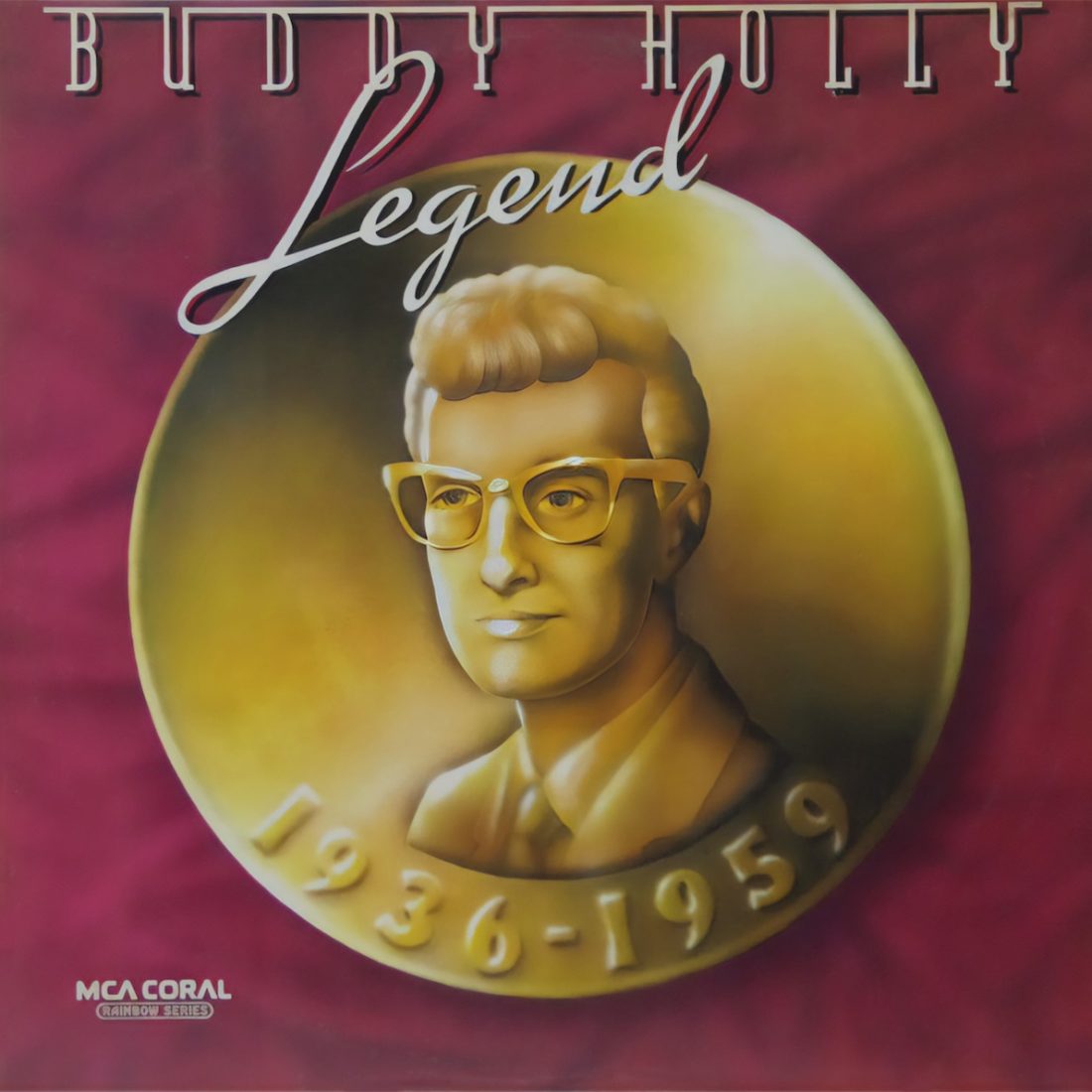

It certainly was. Legend had been a UK-only release a few years earlier and it had everything on 20 Golden Greats and more. Two LPs inside a gated picture sleeve, eight tracks on each side, except Side Two which had nine. Against a burgundy-coloured backdrop, the front had a gold medallion-like image of Holly, the word “Legend” angled across the top of it, and the date of his tragically short life, 1936-1959, along the bottom.

Unlikely Star

On the back were four more small disc shapes listing the tracks on each side, though the art designer had clearly held sway over the compiler because they confusingly jumbled each side’s running order for what they presumably felt was a neater look. Within these discs was a larger picture of Holly himself, in an ill-fitting top, bony hands uneasily resting on his hips. He certainly was one awkward-looking dude.

Back then, as you scrutinised the sleeves of these old rockers, Presley seemed beautiful, beyond this world; Cochran was who you wanted to look like, but knew that you didn’t; and Jerry Lee Lewis, if you were enjoying a good hair day, you might think, ‘Yes, well maybe’. Holly, however, was a long-necked regular looking fella. And yet, for many he shone a torch where previously there had been no light. Suddenly, being a geeky rocker was fine. The short-sighted John Lennon had always performed without his glasses until he saw Holly, but legions of kids in their bedrooms also drew inspiration from the appearance of this unlikely star.

Endearing Mannerisms

Then there was the voice. Mick Farren, reviewing Legend in the NME on its release in October 1974, explained that while Holly was an Elvis imitator, “his vocal register being at least an octave higher than Presley’s presented him with something of a problem. He got round it by singing in a lighter, less delinquent style” and by turning Elvis’ “deep fried Southern sex sob into a coy Texas hiccup”. It meant that 50s teens took him to their hearts “because he made rock singing sound like something anyone could do.”

It’s fair to say that Holly’s voice was an acquired taste. Yet that fragility was weirdly compelling when first heard in the late 70s, by which time we were used to bands whose lead singers seemed to lack the most basic vocal technique. By comparison, Holly was tremulously melodic, and the whinnying mannerisms were endearing.

Invaluable Information

Legend was an eye-opener in another sense. The 70s was still the Dark Ages in terms of information, reflected in the hazy attribution of songs on some rockabilly records of the time. Rock was just starting to assess its back story, and details were scarce, unless you were awake enough to spot the existence of fan clubs, their postal addresses sometimes found on the back of the album sleeves. Was Holly another Sun Records artist? Was he rock’n’roll or rockabilly? Did it matter either way? These were all legitimate questions. At least Legend arrived with extensive sleevenotes by Buddy Holly authority and founder of Rollercoaster Records John Beecher, as well as including details of the recording locations, dates and personnel. The small white type was tough to read set against the black background, but as a potted Holly history this was state of the art for the times.

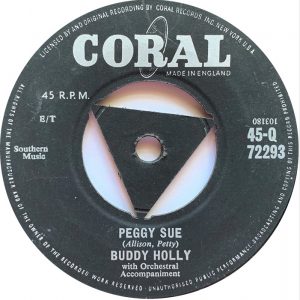

We learnt how the lad from Lubbock, Texas, had driven 90 miles to hook up with Norman Petty in Clovis, New Mexico, and how the producer gave him almost unlimited time to experiment. Peggy Sue was cut early in the morning as “the easy-going relationship with Petty meant that recordings could be made when other studios would have been closed.” Stressing the importance of drummer Jerry Allison, and the way Holly combined lead and rhythm guitar, there were some good anecdotes. The best of them being the recording of I’m Gonna Love You Too, when an actual cricket got into the echo chamber. The cricket couldn’t be located but you can hear it chirping at the end of the song.

Career Highlights

Which songs made most impact on a first timer’s ears? Clearly That’ll Be The Day and Oh Boy! as powerful, no-frills rock appealed to listeners, but so did the rolling beat of Think It Over. You could enjoy the busy backing of vocal quartet The Picks, who supported Holly on many of his early Brunswick Records output – and the funny, coy little squeal of excitement Holly deployed on Tell Me How.

Although it’s perhaps not everybody’s favourite Buddy track, there remains a timeless charm to Everyday, while intoxicating were Words Of Love and Listen To Me, their odd sound coming from the early use of double-tracking. The final side, consisting of the New York recordings, was a striking change of mood.

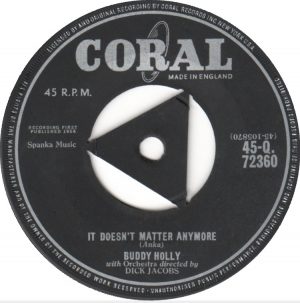

It Doesn’t Matter Anymore, Moondreams, True Love Ways – with its classy saxophone break – and Raining In My Heart all vied for the title of most enchanting Holly song ever. Love Is Strange brought the collection to a beautiful – albeit rather eerie – close.

According to Mick Farren the collection didn’t contain anything new, and certainly nothing for the collector. But we didn’t know that at the time. As the sleevenotes said, the 33 performances on Legend were Buddy Holly’s career highlights. With a newspaper boy’s earnings unlikely to stretch to the 6LP The Complete Buddy Holly, it was plenty to be going on with.

For more on Buddy visit the Buddy Holly Foundation here

Read More – Classic Album: The Crickets’ The “Chirping Crickets”