A ‘second-best of’ by Chuck Berry would destroy most artists’ greatest hits – Here Vintage Rock lists its Top 20 Lesser-Known Chuck Tracks

Words by Douglas McPherson

No rock’n’roller except Elvis has a bigger catalogue of all-time classics that everyone’s heard of than Chuck Berry. The difference is that Chuck wrote nearly all his own material, and the reach of his songbook has been spread even further by countless covers by everyone from Buddy Holly (Brown Eyed Handsome Man) to ELO (with their rockin’ orchestral version of Roll Over Beethoven), the Rolling Stones (Come On) and even Elvis (Promised Land).

But even though greatest hits compilers have never had trouble putting a much-loved favourite on every track of a Chuck Berry collection, those classics only scratch the surface of a body of work that he assembled between signing his first record deal with Chess in 1955 and recording his last studio album in 1979 (excluding his soon-to-be-released final album, cut shortly before his death).

Among the often overlooked gems are brilliant singles such as Tulane and Back To Memphis, which stand with his finest compositions and performances but which, due to the year they were released, fell through the cracks of fate and fashion and never received the airplay or chart action they deserved.

Hail! Hail! Chuck Berry

Then there are a slew of B-sides and album tracks that show many more sides to his talent than his signature Chuck Berry guitar intro and songs about cars, girls, jukeboxes and going to school. Slowies like Blue Feeling and Wee Wee Hours prove he was an exquisite blues man. His rock’n’roll songs, after all, just show what the blues sounds like when it’s sped up. Other tracks reveal his grasp of the other main root of rock’n’roll – country music. He also liked Latin rhythms and sentimental love songs like Time Was.

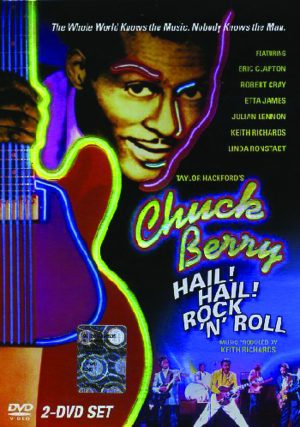

Chuck Berry never stopped rocking. He gave his fans the good-time grooves they wanted, and when he launched into a song like Oh What A Thrill in 1979, he sounded no different to what he had done 25 years before. But, as these 20 tracks prove, there was a lot more to his songbook than his average show or compilation CD suggested. In fact, when he sat down in the middle of filming his 60th birthday documentary Hail! Hail! Rock’n’Roll and casually unfurled the melancholy standard Cottage For Sale, as covered by hundreds of artists great and small, his spellbinding performance suggested there was a storehouse of music within him that he never even committed to tape.

HAVANA MOON (Chess, 1956)

Chuck Berry’s songs are often described as musical novellas, and this brooding, atmospheric B-side to You Can’t Catch Me attests to his novelist’s knack of crafting characters and a sense of place, as well as a compelling story. It also proves his imagination wasn’t confined to teenage lives and American highways. Inspired by a trip to New York where he first encountered the Cuban community as well as by the Latin rhythms of songs like Nat King Cole’s Calypso Blues, which was popular on the club scene at the time, Chuck adopts a local patois (“Me all alone, me open the rum”) to tell the story of a Cuban man slowly realising his American girl won’t be coming back. The original recording made another appearance in 1966 when it was resurrected as the flip to Berry’s Ramona Say Yes single.

COUNTY LINE (Chess, 1959)

This is the same song, but a very different arrangement to Chuck’s low-charting 1960 single Jaguar And Thunderbird, and surfaced as the B-side of a late-1970s bootleg release of Carol. Whereas Jaguar And Thunderbird has quite a hillbilly flavour, thanks to the busy piano tinkling, County Line has a distinctly beat group feel, established by the opening flourish of “Ya, ya, ya” backing vocals. Get past the novelty packaging, however, and it’s a typical Berry car race song, with a lot of Maybellene in its DNA, but also a subplot about a county sheriff trying to catch the racers. Mystery is added by having no mention of the drivers, as if the Jag and ‘Bird are driving themselves.

TIME WAS (Chess, 1959)

It’s one of the gifts of the internet that you can call up on YouTube a truly obscure little gem like Time Was, which was never released at the time of recording, without having to invest in a box set such as The Chess Years. Although a cover of a song written by Bob Russell, Gabriel Luna and Miguel Prado, the nostalgic references to a schoolyard romance make this slow and smoochy dance hall jazz number sound like it could have come from Berry’s pen. Chuck is at his most smooth and mellow on a lazy song full of bluesy changes that would have fitted perfectly into Willie Nelson’s standards album, Stardust.

LA JUANDA (Chess, 1957)

It’s tempting to wonder what an excitable middle school kid who’d just dashed out to buy the guileless dancefloor filler Oh Baby Doll would have made of it when they flipped the 45 to find La Juanda on the B-side. With its slow, swaying Latin rhythm and part-Spanish lyric, rock’n’roll it most certainly is not! There are probably a lot of platters worn smooth on the Baby Doll side and good as new on the flip. But Chuck’s tale of two slow dancers who can’t speak each other’s language is worth a listen if only as an early example of his interest in employing foreign phrases – “Habla solo la langua de Ingles y no comprenda Espanol” – a method which he would later deploy so effectively on the timelessly charming You Never Can Tell.

DEAR DAD (Chess, 1965)

Songs of cars and teenage lives were key to Chuck’s appeal, and of course his young fans didn’t all drive “coffee-coloured Cadillacs” or some other dream-mobile in which the worst problem a driver might face would be a safety belt that wouldn’t budge. Many record-buyers would have driven junkers, and been only too familiar with the frustrations of trying to impress their friends and girls with the sort of clapped-out car that the narrator of this solid rocker is begging his dad to replace. With typical use of detail, Berry mentions almost getting a ticket under a “freeway traffic rule” which means “it’s now a violation driving under 45.” But the real stinger is the young driver’s sign-off: “Sincerely, Henry Junior Ford”.

GO, GO, GO (Chess, 1961)

With references to duck-walking, Maybellene, Sweet Little Sixteen and Johnny B Goode, this was Chuck Berry paying tribute to Chuck Berry in a year when the world wasn’t listening. But, as with Jerry Lee Lewis, Chuck’s hardcore fans have always forgiven his more self-regarding moments because, well, there’s no denying he’s every bit as good as he thinks he is. George Thorogood and the Destroyers supercharged Go, Go, Go in a throbbing rock’n’roll version on their 1985 album Maverick, but Berry’s laid back original has a charm of its own. The tick-tock pace perfectly evokes him duck-walking and “peckin’ like a hen”, while his staccato vocals lay down the blueprint for rap – including the self-aggrandisement.

BACK TO MEMPHIS (Mercury, 1967)

The late ’60s were a long dry spell for Chuck when it came to the matter of chart action, and it wouldn’t be until the next decade that he would return to massive airplay with his unlikely, purloined comeback My Ding-a-Ling. But he really deserved to have got some action with this seriously funky tribute to the Bluff City, replete with blasting horns and a fuller production than he’d used in previous years. Gritty lines about “struggling up here, trying to make a living” and “going hungry in New York and Chicago” perhaps reflected the mileage he was still putting in on the road, but although now an oldies act, this tough R&B song proves he’d lost none of his bite or creativity.

OH WHAT A THRILL (Atco, 1979)

Recorded on the Atco label, Rock It was the last Chuck Berry studio album released during his lifetime, and this was his final single. Some might say he was fast running out of ideas, and from the opening “Oh well, well, well,” it was clear he looked no further for inspiration than his own Back In The USA, which begins “Oh well, oh well,” to the very same tune. All the same, Berry’s melodies and grooves were so strong and so likeable that he could afford to reuse them now and again. With his old pal Johnnie Johnson back on piano duties, the nostalgic lyric is a fine farewell: “I could stay here all evening listening to the music you play, those same sweet songs of a golden yesterday.”

IT WASN’T ME (Chess, 1965)

Extracted from his last album for Chess before jumping to Mercury (although he would eventually return to Chess) this unjustly ignored single features a suitably sly half-spoken vocal to describe a series of suspicious circumstances in which Chuck assures us, with all the shiftiness of a man in the dock, that he was most certainly not the man involved. Chuck liked the chorus enough to couple it with a completely different set of verses that told the story of an escaped felon in Wuden’t Me, on his 1979 album Rock It. But his mid-’60s original is by far the funkier cut, and guest star Paul Butterfield’s harmonica drips from the track like a helping of extra-hot barbeque sauce.

THIRTEEN QUESTION METHOD (Chess, 1961)

If you want to chat up the girl or guy of your dreams, follow Chuck’s Thirteen Question Method, which allocates a question to each line: “Question number nine is where to dine” etc. A stickler would point out that there are only 12 questions, but “thirteen” obviously sang better, and the final query is all the better for being left to our imagination: “Question number twelve is when we’re by ourselves.” Nuff said. Recorded for his 1961 LP New Jukebox Hits, shortly before he went away for an 18 month (ahem) vacation at Uncle Sam’s expense, the playful lyric and cha-cha rhythm would make this period piece ripe for revival by The Mavericks.

BLUE FEELING (Chess, 1957)

Turn over Chuck’s classic single Rock And Roll Music and you’ll find a slice of pure blues in the form of this languid instrumental. Essentially, it’s a duet between Berry and his musical conjoined twin Johnnie Johnson, whose piano was always the perfect foil for Chuck’s guitar. Buyers of Chuck’s second album One Dozen Berrys would have found two versions of Blue Feeling. The second, which forms the penultimate track on Side 2, is the same recording, just noticeably slowed down and re-titled Low Feeling. The Blue Feeling version is the best, though, capturing the lean twang of Berry’s guitar and, in particular, the intensity of Johnson’s ivory tinkling.

TULANE (Chess, 1969)

What a day in musical history it was when Tulane and Johnny opened their novelty shop, as commemorated in this typically colourful and convoluted lyric about a couple of drug pushers being busted by the cops. Chuck never really changed his style to reflect passing trends, but this song cut on the cusp of the ’60s and ’70s is nevertheless given a refreshingly different sound by the harmonica of Bob Baldori, which blows strongly throughout, while subtle variations on Berry’s trademark guitar into and closing lick keep things unmistakably Berryish. If recorded six years earlier this would have been a hit, but it took a faithful 1977 cover by the Steve Gibbons Band to crack the charts.

HAVE MERCY JUDGE (Chess, 1969)

Cut at the same session as Tulane, and released as its B-side, Have Mercy Judge continues the tale of Johnny, caught by the law for “trading in forbidden substances” while his gal Tulane escaped. In contrast to the rollicking Tulane, this is a grinding blues. Berry, of course, knew all about judges, and as Johnny languishes in a cell awaiting trial, Chuck perfectly conveys the cold fatalism of a prisoner who isn’t expecting any mercy. He fully expects to be sent to a “stone mansion” and isn’t relying upon Tulane to be faithful while he’s away. In an interesting insight into the criminal mind, however, he doesn’t begrudge Tulane’s “needs” – he’ll love her all the more when he gets home.

STILL GOT THE BLUES (Chess, 1963)

Contrary to what the title suggests, the 1963 album Chuck Berry On Stage wasn’t a live recording. Half the tracks were previously issued studio recordings, such as Memphis, Tennessee, overdubbed with audience sounds. Just to confuse buyers even further, Sweet Little Sixteen was listed on the sleeve as Surfin’ USA (a song the Beach Boys had written to the melody of Sweet Little Sixteen). As well as a previously unreleased alternative take on Brown Eyed Handsome Man, however, the rest of the songs were new studio cuts, including Chuck’s reading of Willie Dixon’s I Just Want To Make Love To You, and the breezy original Still Got The Blues – an enjoyable slice of jump jive.

LIVERPOOL DRIVE (Chess, 1964)

In 1964 Chuck emerged from prison to find his generation of American rock’n’rollers had been pushed off the charts by British bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. The good news was that those British invaders were partial to covering Chuck Berry songs, as with the Stones’ version of Come On. Chuck responded with the album St Louis To Liverpool, which yielded some of his biggest hits, such as No Particular Place To Go and Promised Land, as well as this engagingly lively instrumental. Nothing about it brings to mind Liverpool or Merseybeat, but as much as his playing has influenced every guitar player who came since, it’s remarkable that absolutely nobody else actually sounds like him.

WEE WEE HOURS (Chess, 1955)

In later years, this languorous little blues song may have brought to mind Berry’s settlement of a class action by women who accused him of filming them as they sat on the toilet of his restaurant. Apart from the title, it’s hard to miss the double entendre in lines like, “In a wee little room, I sit alone and think of you”. In fact, it was the B-side of his first single, Maybellene, and also on the audition tape he gave to Leonard Chess, perhaps suggesting he always considered himself first and foremost a blues singer. The world, of course, wanted him for Maybellene, but this is a fine, sensuous performance reinforced by intense piano rattling from Johnnie Johnson.

WOODPECKER (Chess, 1973)

In 1973 Chuck teamed up with the Greenwich Village rock band Elephant’s Memory, who had previously backed John Lennon and Yoko Ono, to record the album Bio. Chuck, of course, could have teamed up with the New York Symphony Orchestra and it wouldn’t have made him sound any different. Bio’s title track was literally a biography set to music, which leaves no doubt that he went into the project to remind the world of his own Chuckness. He did, however, find a different groove with the funky instrumental Woodpecker, with syncopated handclap rhythm and the sax of Stan Bronstein, over which the guitar licks are pure Chuck Berry blues.

COTTAGE FOR SALE (No Label, 1987)

As such a prolific writer, Chuck is seldom associated with covering other people’s songs, but during the filming of his 60th birthday documentary Hail! Hail! Rock’n’Roll he sat on a couch with his guitar, and the piano accompaniment of Johnnie Johnson, and unprompted sang a touchingly quiet and sensitive rendition of this American standard. Penned in 1929 by composer Willard Robison and lyricist Larry Conley, the melancholy tale of a relationship that’s come to an end has been cut by artists from Frank Sinatra to Peggy Lee, Nat King Cole and even James Brown. Chuck’s heartfelt version, consigned to the film’s DVD extras, begs the question of why he never made an album of standards.

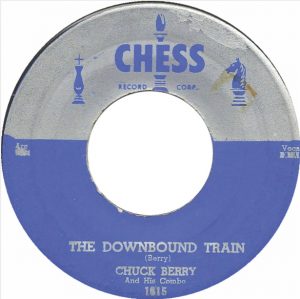

THE DOWN BOUND TRAIN (Chess, 1955)

Chuck always had one foot in the blues and one foot in country music, and never was that more evident than on his fourth single. The A-side No Money Down was a talking blues, while its flipside, The Downbound Train, with its lickety-spit rockabilly rhythm, ghostly echo and general air of foreboding, was so country it might have been recorded over at Sun by Johnny Cash. Inspired by Berry’s Baptist upbringing, the lyric describes a drunk who passes out and dreams he’s on a train being driven by the devil. When he wakes up, he swears off the demon drink. The nightmarish feel is enhanced by the way the song fades in at the beginning and out at the end.

LONDON BERRY BLUES (Chess, 1972)

Following “London Sessions” albums by Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, Chuck travelled to the capital in 1972 to grab a piece of the action and scored his first million-selling LP – thanks to the infamous My Ding-a-Ling. Despite a gutsy, blues-rock feel, the rest of the album didn’t contain Berry’s strongest songs and his voice sounded throaty and strained, but it did include this scorching instrumental which burns with the spirit of all his best rock’n’roll performances steamrollered into a wordless amalgam of what he does best. Coming on like an end of concert jam, with his guitar sounding slightly fuzzier than usual, the track includes a neat three-quarter mark lull before surging back for the finale.

Subscribe to Vintage Rock here

Read More: Top 40 Lesser-Known Elvis Tracks