The emotionally charged singing of Clyde McPhatter inspired Elvis Presley, Jackie Wilson and Smokey Robinson. As a member of Billy Ward And His Dominoes and founder of The Drifters, and as a solo singer, he made many unforgettable records, yet died in obscurity. Here we spotlight his unique artistry…

Words Jack Watkins

Britain in 1960 shaped up pretty well as far as the live rock’n’roll scene was concerned. It started with Gene Vincent being joined by Eddie Cochran on a sensational, but ultimately tragic, tour. The Everly Brothers arrived in the spring, and there were visits from The Platters, Freddy Cannon and Conway Twitty.

In April, a tour featured three American rock’n’roll acts on the bill for the first time ever. From a historical perspective, the lineup of Bobby Darin, Clyde McPhatter and Duane Eddy should qualify as one of those wish-I-could-have-been-there moments. Darin was a multi-talented all-round entertainer. McPhatter was arguably the greatest proto-soul voice of all time.

Overall, however, the tour seems to have been only a patchy success, with Darin, now in his Sinatra phase, disappointing with his choice of material, and Eddy cutting across much better with the shows’ mainly teen audiences. McPhatter was the least known of the trio over here, with only one British hit record to his name, Treasure Of Love, which had been on the chart for one week in 1956, reaching No.27. He seems to have been restricted to about six songs per show. Those who saw him bear witness to the magic of his voice, causing awed silence and then huge applause when he sang Without Love, his million-selling Stateside hit. But what a waste.

Gospel-Charged Electricity

There was one moment on that tour that has found a web afterlife, however, giving a glimpse of McPhatter’s gleaming brilliance and sense of style. When Darin recorded a Saturday Spectacular for ATV, Eddy and McPhatter were guests. Now viewable on YouTube, Eddy performs Shazam! and then plays acoustic guitar while Darin sings about being a country boy. McPhatter does his latest single Think Me A Kiss, delivered at a married man’s pace to accommodate a laughably square orchestra which sucks all the energy out of the song.

McPhatter, to his credit, swings gamely and finishes with one of his trademark rising falsettos. Darin then launches into a piano roll over which McPhatter sings one of the songs that carved his early reputation when a member of Billy Ward And His Dominoes, Have Mercy Baby. Darin gets in the way, but McPhatter is note-perfect and you get a sense of his gospel-charged electricity.

Think Me A Kiss, with its ecstatic ooby-dooby- doobies, was a minor hit back in the States, and typical of the lighter material McPhatter was recording by the early 60s for MGM and Mercury. These songs weren’t bad and demonstrated his range. But they were a far cry from the chance-taking work of a decade earlier.

Do Something For Me

Born in North Carolina in 1932, the son of a Baptist minister, when Billy Ward recruited McPhatter as the lead singer for his vocal group The Dominoes in 1950, he wanted him to sing like Bill Kenny of The Ink Spots. But McPhatter had honed his vocal chops on gospel, not on cooing in the soporific style of the close harmony black groups of the day. Unable, or unwilling, to suppress his more histrionic inclinations, it meant that McPhatter was doing something that at the time was considered sacrilegious, singing secular songs about love with a religious, melismatic fervency.

On the Dominoes’ first R&B hit, Do Something For Me, McPhatter’s exhilarating vocals offset the more conventional close harmony warbling of fellow group members. That’s What You’re Doing To Me and Have Mercy Baby were other thrilling efforts, and when he sang oldies like Harbour Lights and These Foolish Things, McPhatter played around with the lyrics without trashing the structure in the way some later soul artists like Otis Redding would be guilty of doing. Even when Bill Brown took the lead on Sixty Minute Man, sounding like he’d have trouble lasting 60 seconds let alone a full hour, it was McPhatter’s backing vocal energy that made the song. No wonder Atlantic Records boss Ahmet Ertegün lost no time in recruiting him.

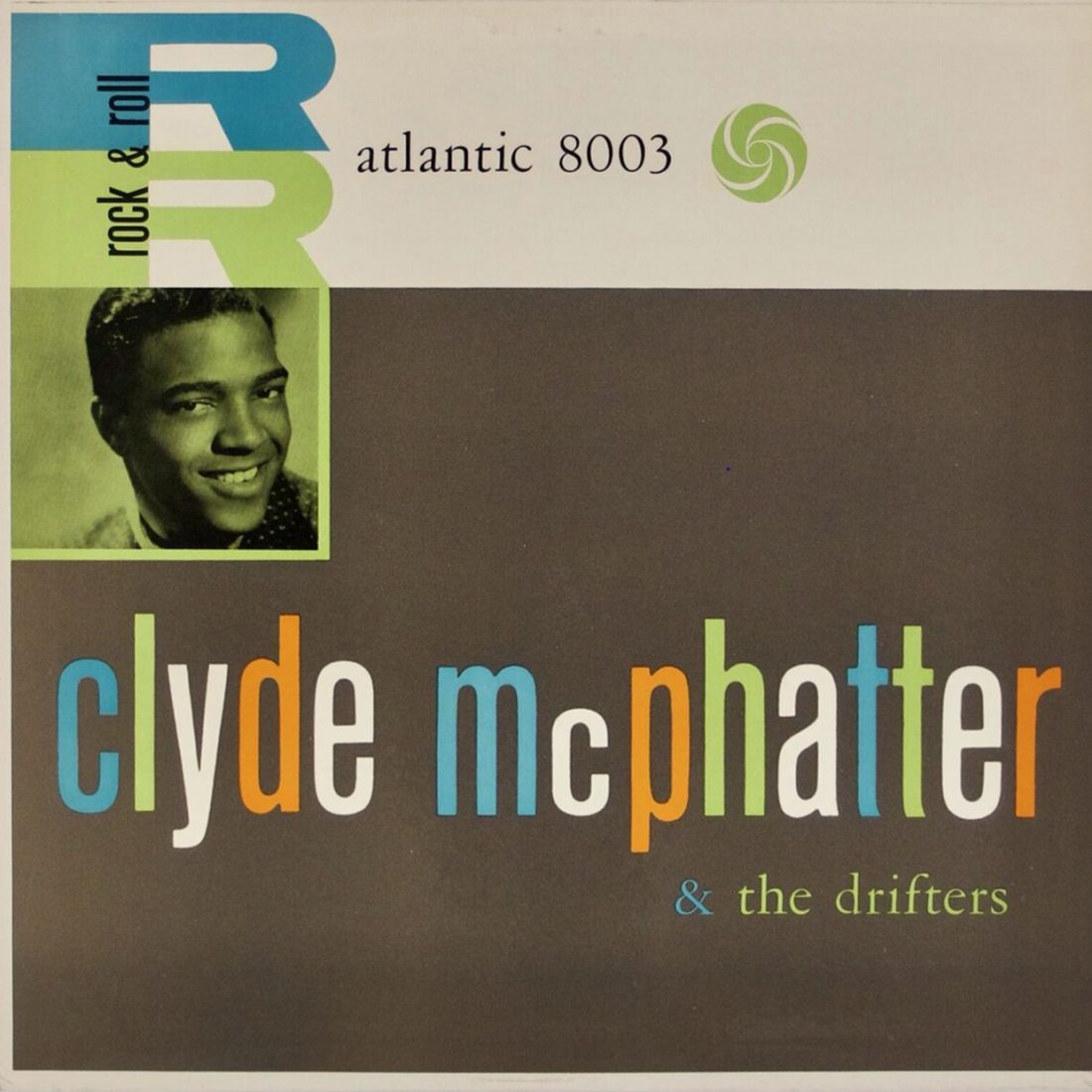

According to the company’s A&R man Jerry Wexler, Ertegün loved “the incredible funk of Clyde’s high lead tenor”. McPhatter was asked to put together a new, rougher-edged vocal group, and what became known as Clyde McPhatter And The Drifters made their first recordings in the summer of 1953. By the end of the yearMoney Honey, from their second session, was on top of the R&B charts.

What’cha Gonna Do

The follow-up single, the Latin-rhythmed Such A Night, later recorded by Johnnie Ray and Elvis Presley, also sold a million copies and showcased McPhatter’s twitchy tenor at its birdlike best, choirboy innocent and cheeky all at once. Honey Love had a mambo rhythm, and when McPhatter sang “I need it in the middle of the night” there wasn’t much doubt about what “it” was. It gave the group their first pop hit. Closely modelled on an earlier version by The Ravens, White Christmas was a sensational reworking of the Irving Berlin chestnut, with McPhatter bouncing off Bill Pinkney’s lead bass baritone vocal like a boisterous kid on Christmas Day.

What’cha Gonna Do, which apparently inspired Hank Ballard And The Midnighters’ The Twist, was a nifty little blues rocker, incorporating a gospel call and response pattern. Another big R&B hit, it’s widely reckoned to be one of the best Drifters recordings.

By now McPhatter and The Drifters were a big draw. McPhatter presented a new kind of black R&B star, boyish and slim compared to mature looking blues shouters like Joe Turner and Wynonie Harris. He wore shiny suits and patent boots on stage, and Jackie Wilson was among those who closely studied his moves, noting their impact on adoring females in the audience.

“The Man”

On particularly intense songs McPhatter would make as if his body had been struck by lightning, stiffening his back and throwing his gaze upwards, before sinking to his knees, moaning and sobbing. Smokey Robinson observed that while young black contemporaries admired the singing of Sonny Til of The Orioles, they didn’t want to be him, whereas McPhatter was “The Man”.

McPhatter decided to break away from The Drifters in 1954, but following a stint in the armed forces, he remained a major rock’n’roll star, lining up in Irvin Feld’s touring Biggest Rock And Roll Show of 1956, a 44-day tour in the company of Bill Haley, Frankie Lymon, Bo Diddley and LaVern Baker. He also appeared in the Alan Freed biopic Mr Rock’n’Roll, lip-synching another new single, Rock And Cry, and its flip You’ll Be There.

But the records, with the exception of Without Love, were getting poppier, and a bit smoother. Not that McPhatter minded. Like many of his generation, he consciously wanted to appeal to the white supper club audience. And the biggest hit of his career lay ahead. In 1958 he was handed a song written by an aspiring young singer, Brook Benton. A Lover’s Question may have been a world away from the gospel fire of Do Something For Me but it was pitch-perfect pop, the simple acoustic arrangement framed round McPhatter’s ardent vocalising. It made No.6 on the pop charts in 1959, and stayed in the Top 100 for nearly six months.

A Tortured Soul

While A Lover’s Question was still in the charts, McPhatter had switched record companies, signing with MGM. It may have been lucrative, but creatively speaking it was a backward move, and his records didn’t sell as well either. Within a couple of months of returning from his British tour with Darin and Eddy, he had joined Mercury, where at least he had sympathetic producers, Clyde Otis and Shelby Singleton, and some more hits like Ta Ta, Lover Please, written by Billy Swan and featuring King Curtis on sax, and a revival of Thurston Harris’ Little Bitty Pretty One.

By the end of 1962 sales were slipping, however. McPhatter’s bright stage persona concealed a loner with a tortured soul, with deep insecurity about his lack of education, his sexuality and of racial discrimination, and he increasingly turned to alcohol for escape. He would continue to make fine records, including a superb Alan Lorber-produced uptown soul album Songs Of The Big City (1965).

Deserving more recognition, it yielded only one hit, Deep In The Heart Of Harlem, which scraped in at No.91, the last of his songs to make the pop chart. Lorber, interviewed by Colin Escott and quoted in the latter’s booklet for a Bear Family Records retrospective of McPhatter’s MGM and Mercury recordings, recalled that the recording process was tortuous because of the singer’s drink problem, but that he “loved working with Clyde. He had such a beautiful velvet quality and that vulnerability in his voice. He was halfway to the grave, I guess, but it enhanced the fragility in his performances.”

Velvet Quality

McPhatter’s last Mercury single Crying Won’t Hurt You Now was another piece of magic. It was ignored and just as the soul scene was booming, McPhatter was becoming a forgotten man. He continued to make interesting records for smaller labels, and was still in good voice when he arrived in England for a tour in 1967, ahead of taking up residency here a year later. But photos taken by Steve Richards during a gig at the Princess Club, Manchester, suggest his appearance was vastly changed, sporting a wig, the boyish looks of yesteryear now a memory.

Richards’ friend Bill Millar, then a budding rock writer, recalls interviewing him in his dressing room for Soul Music magazine: “I was still rather naïve and assumed he was so nervous because I was quizzing him. He signed a programme from his 1960 shows and as he did so I noticed his hand was shaking. It was only later I realised he was a serious alcoholic and had the DTs.” Millar went on to write The Drifters: The Rise And Fall Of The Black Vocal Group in 1971, not only one of the best studies of its subject, but containing a fascinating analysis of McPhatter’s vocal approach which he maintains “created a revolutionary musical style from which, thankfully, popular music will never recover.”

Godfather Of Soul

Elvis Presley once talked about McPhatter to Sam Phillips, remarking, “If I had a voice like that man, I’d never want for another thing.” Other stars may have crashed and burned, but McPhatter seems, as Jerry Wexler put it, to have “just faded into the wallpaper, poor guy.”

Returning to the States after the failure of his British stay, his unreliability meant bookings dried up, and his finances slumped. Reduced to the oldies circuit in the US, when a writer who wanted to interview McPhatter was introduced to him as a fan in 1972, he immediately looked up and said, “I have no fans.” Pitifully, he had rung Atlantic up begging for another chance with them. Their refusal broke his spirit, according to his old labelmate and friend, Ruth Brown. Within less than two months he was dead through liver, heart and kidney failure, resulting from years of alcohol abuse. He was only 39.

McPhatter was posthumously inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 1987. Never an outright rocker like Little Richard or Chuck Berry, he never achieved the racial-barrier breaking commercial success of Ray Charles, Sam Cooke or James Brown. His high, almost feminine tenor was far more subtle than blues belters like Wynonie Harris, and he maybe came too early on to achieve the recognition enjoyed by stylistic descendants like Smokey Robinson and Marvin Gaye. But as Colin Escott has written, “there was a scorching intensity to his best work.” He was the true Godfather Of Soul.

For more on Clyde McPhatter click here

Enjoy this article? Check out Fats Domino – Walking to New Orleans