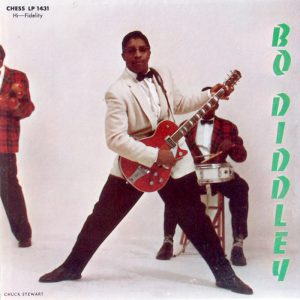

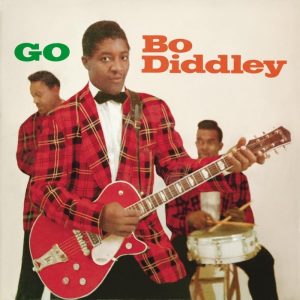

When namechecking the trailblazers of rock’n’roll it’s absurd that Bo Diddley far too often gets overlooked. Vintage Rock rights that wrong by joining his last band leader and bassist, Debby Hastings, in paying tribute to ‘The Originator’…

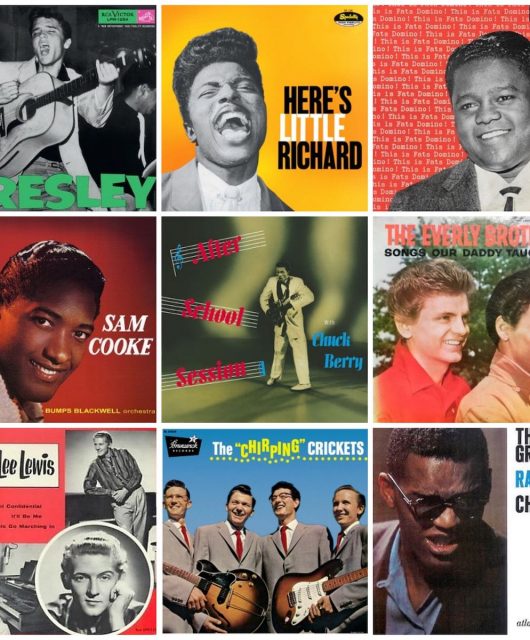

In the autumn of 1963, promoter Don Arden compiled a dream rock’n’roll package tour for UK fans when he teamed up headliners The Everly Brothers and Little Richard with a fledgling Rolling Stones and the pioneering powerhouse Bo Diddley. Performing for audiences on British soil for the first time, the larger-than-life character famed for his splendid self-referential songs and radical rectangular guitars, had already gifted the world a legendary hambone beat that changed music forever.

‘The Originator’ would go on to be a regular visitor throughout the 80s, 90s and into the 2000s alongside his sidekick bassist and band leader Debby Hastings. His last trip here was two shows at Camden’s Jazz Café in July 2006, just two years before he passed away on 2 June 2008.

“The first time I came to England, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger and all of those guys here treated me like a king,” Diddley told Mojo magazine in 2002. “People who say, ‘Oh, Bo Diddley’s the king of rock’n’roll’, I tell them right quick, ‘I’m not a king, baby, but I’m good. Real good.’ I feel like I’m a monument in my own time.”

Hey! Bo Diddley

Diddley was born Ellas Bates in McComb, Mississippi, to Ethel Wilson and Eugene Bates on 30 December 1928.

His biological mother was only 16 years old at the time and placed baby Bo in the care of her cousin, Gussie McDaniel, who raised him as her own. When Diddley’s adoptive father Robert died in 1934, Gussie relocated to the South Side of Chicago where Bo began to take an interest in music.

“Bo would talk about the Ebeneezer Baptist Church where he first took violin lessons with his music teacher, Professor O. W. Frederick,” Debby Hastings tells Vintage Rock. “He liked the violin but he had very large hands, ‘meat hooks’ as he called them, and he was not able to play such a delicate instrument. So, he picked up the guitar. Bo wanted to play like Gene Autry believe it or not.”

Talking with journalist Paul Trynka in 1996, Diddley revealed: “I didn’t play no blues music until I was maybe 13. Up to then, I wasn’t even allowed to listen to any blues music, cause if I did then I’d catch hell from my mother… it was the Devil’s music.”

Thankfully, Diddley disregarded his mother’s scaremongering and succumbed to the music of the Windy City, saying, “If John Lee Hooker could play guitar, I knew I could learn.” He cut his teeth singing on street corners while practising to play a guitar that his sister Lucille gifted him one Christmas. Inspired by the likes of Muddy Waters and Elmore James, he performed with renowned slide guitarist Earl Hooker at the Maxwell Street market. Any cash that he earned playing music in his band The Hipsters, who later became the Langley Avenue Jive Cats, was supplemented by working numerous jobs around town.

Punching In

For an artist who would go on to namecheck himself in so many songs, the origins of the Bo Diddley moniker remains murky and a number of theories exist. However, the man himself revealed in a 2001 interview with Arlene R. Weiss, that it was bestowed on him as a youngster. “I was in grammar school in Chicago and the kids started calling me Bo Diddley,” he said. “I used it when I’d box in the neighbourhood. We called ourselves The Little Neighbourhood Golden Gloves Bunch. We used to spar with each other, stuff like that, so it was like a nickname.”

In late 1954, he teamed up with harmonica player Billy Boy Arnold, drummer Clifton James and bass player Roosevelt Jackson to cut demos of I’m A Man and his eponymous theme tune, Bo Diddley. On hearing the demo, an impressed Phil and Leonard Chess of Chicago’s Chess Records offered Diddley a deal with subsidiary label Checker, and his irresistible take on R&B would go on to completely change the future of music.

Diddley’s pioneering prowess extended far beyond anything many other artists at the time could have envisaged. He developed many innovations with his self-designed, rectangular ‘Twang Machine’, which was later christened a ‘cigar box guitar’ by music promoter Dick Clark.

The Beat Goes On

“I made one when I was a teenager,” Diddley told Vintage Guitar in 1997. “Its pickup was the part of a Victrola record player where the needle went in. I clamped it to the metal tailpiece to pick up the vibrations. I wasn’t able to buy electric guitars back then, so I built them, and they worked pretty good.”

“He was a big man and a prizefighter in his younger days,” continues Hastings. “Bo would dance a lot on stage, perform deep knee bends and jump around. He wanted a slimmer guitar that would make it easier for him to do these stage antics and that’s how he developed what some called the ‘square guitar’. Of course, it isn’t square at all, it’s a rectangle. He was a real innovator and put electronics inside the guitar that would normally be found in an amplifier. The tremolo, echo, EQ, and all of these effects, made the guitar very heavy. He used weighty strings as well.

“When he played, it had a very solid sound. The ‘Bo Diddley Beat’ is very definitive with continuous accents and downbeats, like a freight train chugging along the tracks. If you mention it, people will know exactly what you’re talking about and can sing it back to you. It has come to replace any other references. When he played that rhythm on his guitar, you could feel it deep in your bones. He will always be known for that beat. It’s so profound, so rockin’, so important!”

When Diddley’s Checker debut 45 landed with its belting ‘bomp-ba-domp-ba-domp, ba-domp-domp’ beat, the music world shook with its relentless pattin’ juba rhythm. While the song only topped the Billboard R&B chart for two weeks in 1955, its syncopated sound would reverberate around the world and down the generations.

Beat Box

There have been many high-profile instances of other artists incorporating Bo’s beat in their music. Everyone from Elvis Presley, Duane Eddy, The Byrds, The Who, and Them to David Bowie, Bruce Springsteen, The Clash, U2 and George Michael, have utilised that stimulating stomp. But perhaps the most notable variation came two years after the release of Bo Diddley in 1957 when Jerry Allison tapped out a similar beat on a cardboard box for The Crickets’ Not Fade Away.

Buddy Holly, who was indubitably a fan, had covered Bo Diddley in 1956 and scored a No.4 hit with it in July 1963 when it was posthumously released as a single. Not Fade Away, which was included on The “Chirping” Crickets album, only featured as the B-side to Oh, Boy! and never charted in its own right for Holly. However, The Rolling Stones would rectify that when they broke the UK Top 10 for the first time and took it to No.3 on the British hit parade in 1964.

Talking about how fellow acts latched on to his hard-hitting hambone style, Diddley confessed to Vintage Guitar:

“I didn’t like it at first, because I wasn’t educated in understanding the importance of other people copying your material… When I found out it was good for Bo Diddley, I thought I could go to the bank with royalties, but that never happened.”

London Stomp

Like many other artists to emerge during the burgeoning British beat boom of the 1960s, the Stones would cover Bo’s work or ‘Diddleyfy’ their own tracks. Aside from perhaps Muddy Waters or Chuck Berry, you’d be hard pushed to find another artist who had a greater stranglehold over a young Jagger and Richards than Diddley. However, the admiration was mutual, as Hastings pointed out: “He loved The Rolling Stones. It was early on in Bo’s career when he went to England on tour with them and he was always one of their heroes.”

When Gene Vincent’s manager and gig promoter, Don Arden, offered the Stones a slot on the same package tour as the main man they seized the opportunity and respectfully dropped renditions of tracks such as Cops And Robbers, Crackin’ Up, Diddley Daddy, Mona, Pretty Thing and Road Runner from their set. “For us, the big thrill is that Bo Diddley will be on the bill,” they told the NME at the time. “He’s been one of our great influences. It won’t be a case of the pupils competing with the master, though. We’re dropping from our act on the tour all the Bo Diddley numbers we sing.”

Opening at London’s New Victoria on 29 September 1963, the extensive run of shows was not only the Stones’ first nationwide jaunt, it was also Diddley’s debut visit to the UK. Other acts appearing on the original poster included The Flintstones, a group of musicians who could sit in with an act when required, Julie Grant, Mickie Most and headliners, The Everly Brothers.

Rhythm King

Like the Stones, the inclusion of Diddley on the bill was keenly received by Don and Phil who appreciated his music wholeheartedly. Indeed, Don would later write in his foreword to George R White’s biography, Bo Diddley: Living Legend: “After hearing Bo Diddley for the first time in 1955 my idea of music was forever changed… I think his influence is very evident in my intro to Bye Bye Love, which was my attempt to connect to that same rhythm he alone originated.”

Unfortunately, by the autumn of 1963, all was not going well for the brothers following their earlier split from publishers Acuff-Rose and their hit-making team of Felice and Boudleaux Bryant. Exacerbated by the arrival of The Beatles on the scene, the harmonious duo were experiencing something of a dip in both chart success and popularity. Fearing the tour would be a financial failure, Arden reached out to Little Richard for help in boosting ticket sales. Before you could say, “A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-lop-bam-boom!”, the US firecracker was en route to join the bill as a co-headliner.

The tour kicked off swimmingly for all the star attractions involved. Following Bo’s opening night performance, Chris Hutchins in his NME review wrote: “The familiar strains of the song to which he gave his name earned Bo a warm reception that had turned to something approaching red heat before his startling, though comparatively brief, set was completed.”

Hey Good Lookin’

However, the arrival of Little Richard at Watford’s Gaumont Cinema on 5 October 1963, immediately set the cat amongst the pigeons. Tearing through tracks such as Long Tall Sally, Tutti Frutti, Rip It Up, and Lucille, the flamboyant rocker overran his allocated time slot and would continue to do so night after night. Richard was not only grabbing the headlines but was also stealing the show and fans lapped up the sensational spectacle. It truly was a rock’n’roll education, as Keith Richards remembered in his autobiography: “Little Richard’s stage presentation was outrageous and brilliant.”

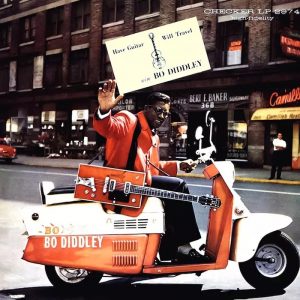

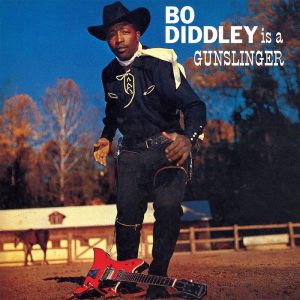

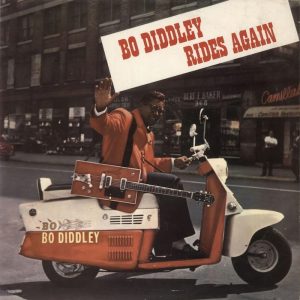

Richard’s theatrics did little to phase Diddley, though, who simply let the music do the talking, and his explosive R&B left fans wanting more. Between October and December 1963 his latest single, Pretty Thing, made the Top 40 and his Bo Diddley, Bo Diddley Is A Gunslinger and Bo Diddley Rides Again albums all hit the Top 20. The tour was heralded as a success for Bo, for fans, and members of The Rolling Stones who got to witness the master deliver the goods every night.

Two years later, Diddley was back in Britain for a second time. In the interim year Bo Diddley’s Beach Party album had spent six weeks in the Top 20 while his Hey, Good Lookin’ single also broke the Top 40 in August 1965 when it made No.39.

I’m A Roadrunner Honey

Sadly, the ’65 tour was a mismanaged affair and stumbled its way around Britain before Bo skedaddled back to the States prior to the final show on 18 October. Despite all the problems encountered, Bo still left a lasting impression on one particular fan, future Rolling Stone, Ronnie Wood, whose band The Birds opened for the star at London’s 100 Club on 28 September. Writing for The Guardian, Wood remembered: “He didn’t have a band with him so he asked us if we could back him up. What made him so great was his freedom, his reckless abandon, and the confidence that shone through in his music.

“I got to know him really well and he was always very affectionate towards me,” Wood continued. “He would more or less sit you on his knee, a bit like your granddad, and tell you a story about back in the old days.”

“Ron was Bo’s good friend,” confirms Hastings. “They would go on to tour together for almost two years between 1988 and 1989. I was on the road with them and they had a lot of fun ‘cutting’ each other up. I remember there was always a lot of laughter going on. Bo loved life on the road and didn’t mind living out of a suitcase. He very much liked touring the UK and loved to meet fans over there. He enjoyed holding court like the king!”

Ahead Of His Time

For that first 1963 tour Diddley brought his manic maraca shaker Jerome Green and glamorous guitarist Norma-Jean Wofford with him on the road. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Wofford was Bo’s second female guitarist, replacing Peggy Jones who was better known as Lady Bo. Jones joined Diddley’s band at just 16 years of age and recorded with him from 1957. Appearing on singles such as Hey! Bo Diddley, Road Runner and Bo Diddley’s A Gunslinger, Lady Bo would state: “Yes, Bo Diddley helped shape the sound of rock’n’roll, but I did too because I was there by his side.”

When Jones left Bo in 1961 to start her own group The Jewels, later known as Lady Bo & The Family Jewel, Diddley recruited Wofford and christened her The Duchess. Known for her sultry skin-tight stage outfit, the protective band leader would tell male admirers that she was his sister. Leaving the band to focus on her family in 1966, Diddley later stated: “We did everything together. She was like family, which was why I told everyone that she was my sister.”

In a time when it was rare for women in rock’n’roll music to be anything other than backing singers, Diddley challenged the norm and placed his female associates firmly in the spotlight. “He never talked about being a supporter of female musicians in particular,” revealed Hastings, who followed Lady Bo and The Duchess when she joined Diddley’s band in the early 80s. “To him, it made no difference. Women have always been able to play

as well as men and he embraced the reality of that, unlike others. For him it was silly to do otherwise, he was very progressive and ahead of his time.”

Sweet Side

“I can’t pinpoint the first time I heard Bo or the ‘Bo Diddley Beat’,” says his friend and collaborator. “It’s just always been a part of my musicality and anybody who has ever played rock’n’roll is very familiar with it.”

Hastings, who played with him longer than the likes of Lady Bo and The Duchess, also acted as his music director since 1994. “He loved to improvise on stage and it was rarely the same way twice,” Hastings continues. “My job was to count off the tunes in the right tempo, bring the band in, signal stops such as in the middle of Can’t Judge A Book, and also cue the endings. I would shape the improvisation in a way that made it interesting for us and also pushed Bo into a place he had maybe never been before. Sometimes I would take it pretty far out.

“He was such an imposing figure and had a very strong stage persona. He took over the stage like a storm cloud. You were enveloped in the thunder and the lightning and it wouldn’t let go!

“Bo had a very good sense of humour and also had quite a sweet side. He always thought of his people back home and the kids in the neighbourhood. I remember how he would make sure to get enough T-shirts to pass out to those kids. It was always 32 shirts for Bo and six for the band. He could also be obstinate and ornery. He didn’t trust people very much, although he trusted his management and me. We always had his back.”

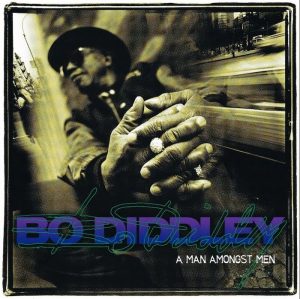

A Man Amongst Men

When Diddley died, aged 79, at his home in Florida, Hastings joined numerous family members and his manager, Margo Lewis, to be by his side. “I had been called down the day before because it was expected,” Hastings recalls. “I had alone time with him throughout the day and I just sat with him, held his hand, and told him what an honour it was to be able to share the stage with him. His eyes were closed, but I know he heard me because he would give

a little smile.

“Bo loved his manager Margo and the two were very close right up to the time that he actually passed. He called her over, blew her a kiss, and I will never forget that tender moment. Family members started singing a hymn called Walk Around Heaven. When it was over, Bo spoke his last words: ‘Wow, I’m goin’ to heaven’.”

Rock’n’Roll Trailblazer

When considering the trailblazers of rock’n’roll, it seems criminal that ‘The Originator’ is often overlooked. “I opened the door for a lot of people and they just ran through and left me holding the knob,” he told The New York Times in 2003. So Vintage Rock wonders how Bo would feel about the fact we’re still talking about him today and continue to enjoy his music. “He was absolutely right to say that, after all he was their father/grandfather,” Hastings replies. “As an innovator, I think that he was disappointed, upset, and frustrated. He didn’t follow them, they followed him.

“I know he was upset with Elvis. Bo would tell me about seeing this young white kid at shows who would often watch him from the wings. The kid was brought in specifically to watch what Bo was doing on stage and that kid was Elvis. When we played Memphis, Tennessee, we took Bo to Graceland. What a mistake that was… The white kid ran over the black kid… boy, did he ever.

“For me, Bo Diddley is the rock that the roll was built upon and I think he would be very happy that he put his deep stamp on music. And you can’t really ask for anything better than that can you?”

Did you enjoy this article? Why not check out When Rockabilly Shook The World

Subscribe To Vintage Rock Magazine Here