Hamburg, the city of sin, transformed The Beatles from amateurs into a raucous, super-tight outfit who could rock the club all night long. David Burke has the story…

The Beatles may have come from Liverpool, England – but they were made in Hamburg, Germany. That, at least, is the view of Allan Williams, the Fab Four’s first manager and booking agent. It was Williams who drove the group, and five others, in an Austin Minivan onto the ferry at Harwich on 16 August 1960, to the Hook Of Holland, from where they travelled to what was once Germany’s main seaport, the third largest in the world, before being reduced to rubble by bombing raids during World War II. By the time The Beatles arrived, Hamburg had become notorious for its vice trade and other criminal activity.

In all, The Beatles played some 281 concerts over five separate visits to the city from August 1960 to December

1962 – including at one point, in 1961, 98 consecutive nights, starting at 7pm and finishing at 7am the next morning.

“It was our apprenticeship. I’d have to say, with hindsight, that Hamburg bordered on the best of Beatles times,” George Harrison recalled years later.

According to Williams, the gruelling live schedule “would make or break any group – it made The Beatles. There’s a sign in Mathew Street in Liverpool: ‘Where It All Began’. But it didn’t begin there. It began in Hamburg.”

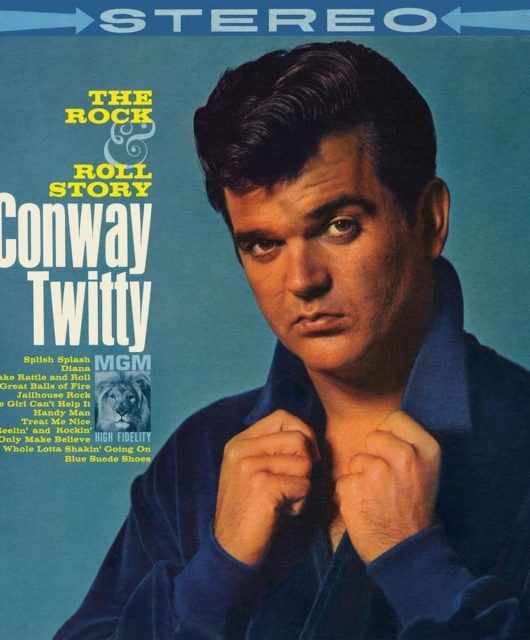

Williams was not wrong. Arguably, those couple of years in Hamburg represent the most significant chapter in The Beatles’ development from just another British beat combo to the greatest rock ’n’ roll band in the world-elect. It was where they perfected their performance skills, enhanced their reputation and as a result of their stint, came to the attention of Brian Epstein, a Royal Academy Of Dramatic Art dropout (his classmates included Peter O’Toole, Albert Finney and Susannah York) who eventually became the band’s manager. They made the transition from a covers band, reworking the hits of the day (including Chuck Berry’s Roll Over Beethoven, Little Richard’s Long Tall Sally and Gene Vincent’s Be-Bop-A-Lula), to composers in their own right – though it’s unlikely anyone was prepared for the global phenomenon The Beatles would eventually become.

Lennon’s look as well as his charisma was what sold aspiring guitarist George Harrison to join the Quarrymen in February 1958, when he encountered them at Wilson Hall in Garston.

“I remember being very impressed by John’s big thick sideboards and trendy teddyboy clothes,” he said. Several months later, Harrison, despite being younger than the others, was recruited. Then came Stuart Sutcliffe, an art-college mate of Lennon’s. “Stuart and John were on the same wavelength but they were opposites,” said Lennon’s then-girlfriend, Cynthia Powell. “Stuart was a sensitive artist and he was not a rebel, as John was. He wasn’t rowdy or rough. But they complemented each other beautifully. John taught Stuart how to play bass. He wasn’t a musician, but John wanted Stuart to be with him.”

In January 1960, Sutcliffe used the £60 he’d won in an art competition to buy himself a Höfner President Bass, and this secured him a place in the Quarrymen. He suggested another name change, first to The Beatals, which evolved into The Silver Beetles by May and finally The Beatles in August. “Stuart was the dominant icon originally,” said Sutcliffe’s sister Pauline. “But there wasn’t any question in his mind that John knew more about rock music, so in the band, John was definitely the leader.”

British musicians had been crossing the Channel and travelling through Holland into Germany – destination Hamburg – since the beginning of 1960. Those from the south of England were recruited at the 2i’s Coffee Bar in London’s Soho by Bruno Koschmider, a German club owner. Acts were recruited in the north by Allan Williams, a Liverpool entrepreneur who owned The Jacaranda, a coffee bar in

the city.

Young Germans were so desperate for rock ’n’ roll that even an amateurish five-piece helmed by Lennon and McCartney could secure dates there. “Before we went over, it was all Italian ‘Cho-cho-bambino’-type music in white suits,” said Williams. “We absolutely wiped the floor with them. We were just there at the right time in the right place – people were hungry for this rawer type of music.”

Williams had already enjoyed success in Hamburg with another of his protégés, Derry And The Seniors (later known as Howie Casey And The Seniors), when he decided to send The Beatles over. They didn’t even have a permanent drummer at the time – Ringo Starr was still with Rory Storm And The Hurricanes. Indeed, Williams had wanted the Hurricanes to make the trip, but they were committed to a season in Butlins holiday camp.

McCartney desperately searched for someone to fill the drumming position for Hamburg – not an easy task, as drummers were “few and far between”, owing to the expense of a drum kit at the time, said Lennon. Harrison – who, along with Stuart Sutcliffe, completed this incarnation of The Beatles – had seen Pete Best with the Blackjacks in the Casbah Coffee Club. After the Blackjacks folded, McCartney invited Best on the Hamburg trip, promising him a fee of £15 a week. Best sacrificed the opportunity to train as a teacher, deciding that Hamburg would be a better career move.

Their first gigs were at the Indra, a grubby strip club that was located in the St. Pauli quarter, a well-known hangout for prostitutes and a dangerous place for strangers to hang around.

“It was a completely different culture,” said Best, “but we were from a dockland city, so we could handle ourselves. It did set us back a little at the beginning, when we got to St. Pauli and found it was the red-light district of the world, with gangsters, prostitutes and 24-hour-a-day booze. It was like, “Wow, this is different from Liverpool”. But then we rolled our sleeves up. We were rock ’n’ rollers and we were living the rock ’n’ roll life.”

They may well have been living the rock ’n’ roll life, but their accommodation at this time was more Skid Row, as McCartney explained: “We lived backstage in the Bambi Kino [a cinema], next to the toilets, and you could always smell them. The room had been an old storeroom, and there were just concrete walls and nothing else. No heat, no wallpaper, not a lick of paint, and two sets of bunk beds with not very much covers. We were frozen.”

After 48 nights at the Indra, The Beatles moved down the Grosse Freiheit to the Kaiserkeller in October 1960, alternating sets with Rory Storm And The Hurricanes. Lennon remembered: “We had to play for hours and hours on end. Every song lasted 20 minutes and had 20 solos in it. That’s what improved the playing. There was nobody to copy from. We played what we liked best and the Germans liked it as long as it was loud.”

Even Best was roped in to sing a couple of numbers each night, among them Carl Perkins’ Matchbox. “And because there was an audience reaction, the lads thought it would be a good idea to get out front to do [Joey Dee’s] Peppermint Twist, and to dance the twist and shake my backside and give a little more showmanship to the band. It was role reversal, because Paul jumped on the kit. We enjoyed the fact that we were doing something different.”

Photographer Astrid Kirchherr, who became Stuart Sutcliffe’s girlfriend, saw The Beatles for the first time playing at the Kaiserkeller. “It was so packed, very low ceiling and smoky and dark,” she remembered. “The first one I saw was Paul, because he used to jump up and down. Then I saw George and thought, this can’t get any better. Then John, and I nearly freaked out. And then there was Stuart, the best-looking of the lot. He used to play with his back to the audience, then he turned around with his dark glasses on and looked absolutely amazing. There was so much joy in their faces, the energy in their eyes, the sense of fun.”

The punishing regime helped to turn The Beatles into rock ’n’ rollers to be reckoned with, as their sound became tougher. They were also learning from other Brits there at the time – Tony Sheridan, a young Londoner who already had US tours with Gene Vincent and Jerry Lee Lewis under his belt, and boogie-woogie pianist Roy Young.

John Gustafson, a member of The Big Three and later the Merseybeats, said that “all the Liverpool guys looked up to Tony. He was a great guitarist, a great singer. He had the legs – the long skinny legs. He had that persona, that ‘I’m a rock star’ thing. A lot of guitarists copied his style… George Harrison, for one.”

“The Beatles would come and talk to us about technical musical things,” added Roy Young. “Tony played a shuffle rhythm on guitar, and I’d play a straight rhythm on piano. People didn’t know how we did it. That was what they [The Beatles] were interested in.

Sheridan admitted that there was a lot of copying from each other, adding “It was a small academy of fanatical musicians. The Beatles were of that kind, and so was I. When people talk about sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll, it wasn’t like that at all. It was 80 per cent music. It was music, music, music.”

And in its own way, the music helped to heal the rift that had opened up between British and German people in the Second World War. Sheridan had no doubt that the shows they did were about helping people with reconciliation.

Horst Fascher, a former German featherweight boxing champion turned bouncer who became a sort of minder for The Beatles, had fond memories of the British invasion. “We didn’t hate those guys, we loved them because they brought us the new style of music. They helped us to do what we wanted to do, not listening to shit music under Hitler.”

Ah yes, Hitler. Provocateur Lennon, tanked up on ‘prellies’ (slang for Preludin slimming pills) and German beer, goose-stepped across the stage on one occasion screaming, “Sieg Heil!” and “F**king Nazis!” Only a faulty PA, which meant the audience couldn’t hear what he was shouting, saved him from a beating.

If Lennon’s Goonish antics were getting him noticed, marking him out as a maverick who could be either boorish or brilliant, The Beatles’ contemporaries were impressed by their evolution into an exciting rock ’n’ roll band whose raw energy was matched by their improving musical chops.

“We got better and better and other groups started coming to watch us,” notes McCartney. “The accolade of accolades was when Sheridan would come in from the Top Ten, the big club where we aspired to go, or when Rory Storm or Ringo would hang around to watch us. What’d I Say was always the one that really got them.”

Because their rendition of the Ray Charles tune was so extended, it was an opportunity for The Beatles to walk off and wash and drink before returning. In a letter to his mother, Sutcliffe wrote: “We have improved a thousand-fold since our arrival and Allan Williams tells us there is no group in Liverpool to touch us.”

On 18 October 1960, Williams arranged a recording session for Lou Walters of the Hurricanes in a small Hamburg studio. Lennon, McCartney and Harrison were drafted in to play and to sing harmonies, while Starr drummed for his Hurricanes sidekick. They laid down three tracks altogether – Fever, September Song and Summertime – and the session became the stuff of history, as it was the first documented recording that featured the collective unit of Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Starr.

That December, the band went back to Liverpool without Sutcliffe, who remained in Hamburg with a cold. Chas Newby deputised for him on bass at the Casbah Coffee Club, and was shocked at how much The Beatles had improved since decamping to Germany. They were louder, too, with Best adopting a more aggressive approach on his skins at the behest of McCartney. “Crank it up,” he would often instruct him.

At the end of The Beatles’ second stint in Hamburg’s Top Ten Club in 1961, Sutcliffe announced he was quitting to pursue his art studies. He loaned McCartney (who reluctantly took over on bass) his Höfner President model, but asked him not to change the strings around (McCartney continued to play it upside down until he could afford a specially-made left-handed guitar of his own). 13 months later, Stuart Sutcliffe was dead, from an undiagnosed brain haemorrhage.

No history of The Beatles would be complete without acknowledging Sutcliffe’s formative role, however much historians of the group have decried his musicianship in the half century since his tragically early demise. Yet Mersey Beat magazine founder Bill Harry said: “Pete Best was telling me how good he was in Hamburg and how his Love Me Tender was one of the highlights of their act. People seem to have decided now that he wasn’t a good musician, but most of the people at the time said he was very good. He had a very good reputation.”

Minus Sutcliffe, the other four Beatles went into a Hamburg studio in 1961 to back Tony Sheridan on rocked-up versions of the songs My Bonnie and The Saints for Polydor. They were billed on the release not as The Beatles, but as the Beat Brothers.

The session was produced by renowned band leader Bert Kaempfert, who had enjoyed a hit earlier that year with the instrumental Wonderland By Night, a chart-topper in the United States. Kaempfert had seen The Beatles and Sheridan together at the Top Ten Club.

“He thought that I was a preferable candidate [to record]. They were a bit too crazy for him,” said Sheridan. “Bert Kaempfert didn’t have the right nose to smell out the talent of The Beatles. But it was already there, it was see-able and hear-able. He felt there was something good about the guys, but he had no idea what to do with them.”

Brian Epstein was already a fan of The Beatles when he heard My Bonnie. He was persuaded to see them on their next appearance at the Cavern, a lunchtime date on 9 November 1961.

“I was immediately struck by their music, their beat and their sense of humour on stage,” he enthused. “And even afterwards, when I met them, I was struck again by their personal charm. And that’s really where it started.” Brian Epstein eventually became their manager on 24 January 1962, signing the band to a five-year contract.

By the time of The Beatles’ second tenure at Manfred Weissleder’s Star-Club in Hamburg (which boasted a capacity of 2,000 and cinema-style seating) in November of that year, Starr had replaced Best on drums. Best’s dismissal was prompted by producer George Martin opting to use a session drummer on recording sessions. The band left the dirty job of firing him to Epstein, and lacked the moral courage to ever speak to their old friend again. In hindsight, Lennon admitted: “We were cowards when we sacked him. We made Brian do it.”

Best was never given a reason for his expulsion. “Because you’re kicked out, people say, ‘Oh, you were a different kind of person.’ I wasn’t,” Best said in 2009. “We were a unit, and people recognised us as a unit. Every damn antic they got up to, I was part of.”

The personnel change seemed to make little difference to their full-on rock ’n’ roll sound. You can hear it on the 1977 Bellaphon release, The Beatles: Live! At The Star-Club in Hamburg, Germany; 1962, a double set featuring a mix of covers and originals, including I Saw Her Standing There, Twist And Shout and Shimmy Shimmy. Reviewer John Swenson from Rolling Stone magazine called the album “poorly recorded but fascinating,” adding that it showed The Beatles as “raw but extremely powerful”.

By common consent, that hectic two-year period between 1960 and 1962 characterised The Beatles’ apotheosis as a rock ’n’ roll tour de force, as crucial in the advancement of the genre as many of their American peers. “In Hamburg, we got very good as a band, because we had to play eight hours a night and we started building a big repertoire of some of our own songs, but mainly we did all the old rock songs,” said George Harrison.

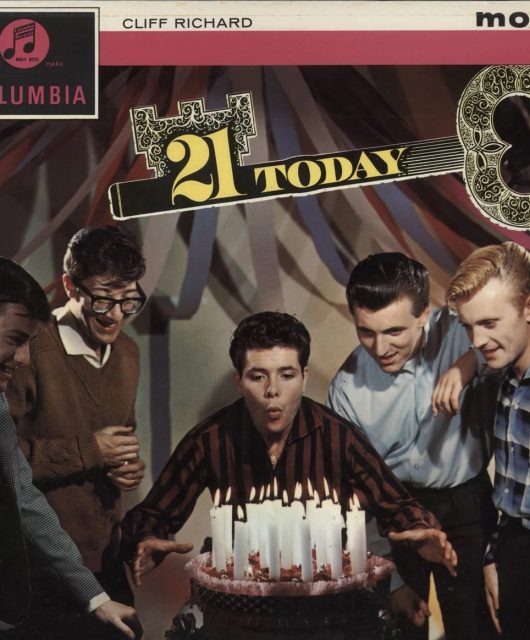

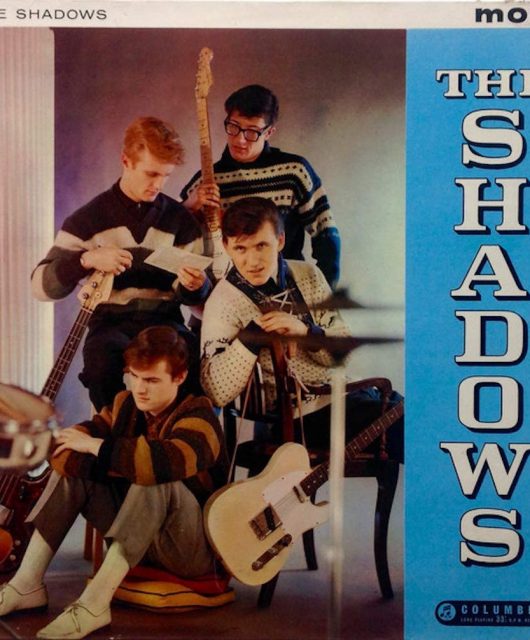

“It was a period in England when it was all about matching ties and handkerchiefs and doing really safe routines like The Shadows, and we weren’t there for that,” he added. “So we just kept playing the rock ’n’ roll things.”

Perhaps Johnny Hutchinson of The Big Three put it best when he quipped: “It was as though The Beatles had gone to Hamburg as an old banger and had come back to Liverpool as a Rolls-Royce.”

Others, however, were less enamoured with the direction in which Epstein was steering The Beatles. For John Gustafson, the advent of Love Me Do, their first single on Parlophone, was the end of their rock ’n’ roll years.

“They were a roaring rock ’n’ roll band in leather jackets and cowboy boots – but they changed,” he said, with heartfelt regret. “The suits came in. It was the Epstein effect.”