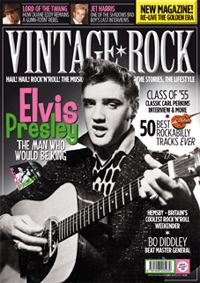

On 24 March 1958, the King Of Rock’n’Roll became Private Presley US53310761. Sixty-five years on from his induction we remember Elvis’ army years…

When the complete story of Elvis Presley is told, there’s a tendency for biographers to partition his life into two parts – the pre-Army, and post-Army Elvis. It’s a handy carving line, separating the raw, hip-swinging Sun Records-era Presley and the more considered artist that emerged after. It’s no surprise that when Thom Zimny paced out his two-part documentary, The Searcher, in 2018, he chose the end of Elvis’ military life to close that first episode.

“Elvis died the day he went into the Army,” so said John Lennon, but how accurate really is that? It’s not as if Elvis did little of note after 1960. If something in Presley had been extinguished that day in March 1958 then how does that explain Return To Sender (1962) or Suspicious Minds six years later, or even 1972’s Burning Love? How can we have had Viva Las Vegas (arguably his best movie) or Flaming Star (possibly his best acting performance)? And what about the ’68 Comeback Special? Could Elvis really have been that sexy, that electrifying, that goddamn vital if the US Army had truly tamed this rock’n’roll animal?

Yet it’s a myth that’s become frustratingly embedded in the oft-told story of Elvis, and is an opinion held by many original fans. “I always thought [his time in the military] ruined Elvis,” Paul McCartney is quoted as saying in his authorised biography, Many Years From Now. “We liked Elvis’ freedom as a trucker, as a guy in jeans and swivellin’ hips. But [we] didn’t like him with the short haircut in the army calling everyone ‘sir’. It just seemed he’d gone establishment, and his records after that weren’t so good.”

For many fans, the footage of Elvis having that much-copied haircut shaved off was a seismic moment, a symbolic castration of the wild boy of rock’n’roll. But Colonel Tom Parker, Elvis’ manager, didn’t see it like that. Elvis could have swerved his national duty by simply enlisting in the Special Services, the entertainment branch of the US military, which would have involved performing for the troops and a chance to live in priority housing. Special Services was known, however, as “the celebrity wimp-out” and the Colonel didn’t want his boy’s image tarnished by taking the easy option. Though the army also offered the chance for Elvis to tour its bases to boost morale, Parker convinced Presley to turn them both down. “Taking any of these deals will make millions of Americans angry,” he’s quoted as saying in Pat Broeske and Peter Harry Brown’s book Down At The End Of Lonely Street: Life And Death Of Elvis Presley.

The singer was originally set to be inducted in January 1958, except Paramount had scheduled the filming of King Creole, Elvis’ fourth movie, for 13 January through to 22 March. Explaining that the studio had already ponied up to $350,000 on pre-production and that many jobs were dependent on it going ahead, the Memphis Draft Board agreed to his deferment, inking the new date of 24 March, just two days after filming was due to wrap.

On that Spring morning, Elvis set off for the draft board on South Main St. with his parents, his then-girlfriend Anita Wood, pal Lamar Fike and, of course, the Colonel, where he was given a medical and serial number. From that moment he was Private Presley US53310761 with a monthly wage of just $78.

After travelling to Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, the new recruit was given his fatigues and boots. So far, so normal. Except his fellow inductees didn’t have to endure a press conference as they started their new life. “Elvis, you don’t get out of the army until 1960,” one reporter asked him, “if rock’n’roll should diminish in popularity or disappear, what would you do?” Breaking into a nervous smile, the King replied, “I would probably try acting.”

Transferring to Fort Hood in Texas, Elvis began his training. But as one of the most famous faces in the world, he knew that all eyes would be on him. Desperate to be thought of as one of the boys, he sought to befriend as many recruits as he could, particularly those in his hut, for whom he bought lunch on their first day as well as an extra set of fatigues.

Almost immediately, life at Fort Hood provided a brutal culture shock. “I’ve eaten things in the army that I’ve never eaten before” he’s quoted as saying in Ray Connolly’s biography Being Elvis, “and I’ve eaten things I didn’t even know what it was. But after a day of basic training you could eat a rattlesnake.” Within weeks, the already svelte Elvis had shed 12 pounds.

While Presley was doing well in training, and appeared chipper to his fellow recruits, inside he was desperately unhappy. Before going in, he’d been worried at what effect two years out of the limelight would have on his career. That worry hadn’t subsided, but on top of that, he was lonely. Luckily, he was helped by a sympathetic sergeant named Bill Norwood who allowed the distraught Elvis to use his home on base to phone his parents Vernon and Gladys and to hook up with Anita. If anything saved Elvis’ sanity in those first months, it was Bill Norwood’s generosity.

Some time later, Elvis discovered that, according to army regulations, a soldier was allowed to live off-base if he had dependents in the area. Before long, he’d moved Vernon, Gladys, his grandma and his friend/employee Lamar Fike into a rented house in the nearby town of Killeen. With his family close by, Elvis seemed to relax. Now he could unburden himself without fear of his grumblings being leaked in the press. Elvis’ peace, though, would be short-lived. Within just two months, his mother was taken ill with hepatitis. A few days later, her doctor sent Elvis an urgent message. His mother was gravely ill.

Gladys Presley died on 14 August 1958 aged just 46 of a heart attack as a result of cirrhosis. At the funeral, Elvis sobbed uncontrollably, even lunging towards the grave as the coffin was lowered into the ground, causing Lamar Fike to pull him abruptly back.

Just five weeks after her death, Elvis and his unit travelled to New York City where they were to embark for West Germany. Of course, the Colonel wasn’t going to let an historic moment like this pass by without media attention and a press conference was convened with Elvis, the Colonel and RCA’s top brass in attendance. One reporter even asked if Elvis would be selling Graceland to which the Private simply replied, “No, sir, because that was my mother’s home.”

Shortly after, Elvis walked up the gang plank of the USS George M Randall, in front of a sea of photographers, ready for his first trip to foreign shores. After disembarking at Bremerhaven in October 1958, he was assigned to the 1st Medium Tank Battalion, 32d Armour, 3d Armored Division, at Ray Barracks in Friedberg where he would serve as an armour intelligence specialist.

Yet again, Elvis was given permission to live off-base. Renting a five-bed house in nearby Bad Nauheim, the newly-widowed Vernon, plus Elvis’ grandma and friends Pike and Red West, were flown over and made No.14 Goethestrasse their new home.

Not that Elvis relied only on his old-time pals and family while in Deutschland. While there, he’d befriended a soldier named Charlie Hodge. Hodge had been in a gospel quartet as a teen and first met Presley in 1956, backstage at ABC’s variety show Ozark Jubilee. Three years later they bumped into each other once more and this time became bosom buddies. Hodge convinced Elvis to help him put together a show for the troops, but Presley previously had it drilled into him by the Colonel that he shouldn’t be performing for free, and agreed, on the condition that he play piano in the background.

By all accounts, Elvis had a whale of a time in Germany. Alongside Hodge he’d begun to refine his voice. Charlie had studied singing with country stars Gene Autry and Red Foley, teaching Presley breathing tricks and how to make the most of his voice. Together, they’d sing hymns and listen to new records sent by Anita. “I guess I got in more singing than I would if I had been working on it,” Presley later told the Memphis Press-Scimitar.

When he wasn’t working or exercising his larynx, Elvis would busy himself playing touch football, going to movies, listening to the American Forces Network and occasionally venturing outside for gigs (he saw Bill Haley twice). Despite it being Elvis’ first time overseas, however, he had little interest in sightseeing or learning the native language. Neither did he ever take advantage of the further educational classes that the army offered. In Germany, Elvis worked hard but partied even harder.

Although Presley was still with Anita and wrote to her regularly, fidelity wasn’t one of his strong suits. He had scores of affairs in Germany, but hadn’t had a thunderbolt moment until he met a 14-year-old by the name of Priscilla Beaulieu. The daughter of an army captain, she’d only been in Germany for three weeks when, one night, she found herself in the Eagle Club on the US Wiesbaden base where a soldier named Currie Grant asked her if she’d like to meet Elvis Presley. When she walked into No.14 Goethestrasse, Elvis was instantly smitten.

Amazingly, the fact that Priscilla was 14 never did leak, and torpedo Elvis’ career in the way scandal had engulfed Jerry Lee Lewis in the wake of his engagement to his 13-year-old cousin. Certainly, Priscilla’s parents approved of the relationship – Elvis made sure he met them to put their minds at rest, and made a point of calling her father ‘sir’.

If Beaulieu Sr had known how much Elvis was corrupting his daughter, however, he might not have been so forgiving. Elvis had been supplying Priscilla with amphetamines to keep her awake at school after spending half the night at his. And it wasn’t just her – Elvis’ pill-popping had revved up in the army. They’d long been a part of Gladys’ life and now they were part of her son’s. Dexedrine was dished out like candy to the soldiers, the theory being it would help them stay awake on guard duty overnight.

But, of course, for Elvis one pill was never enough and before long he was popping them every day. It was an addiction that would stay with him for the rest of his life.

It was March 1960, almost exactly two years on from his induction, when Elvis was finally discharged. At a press conference in front of German reporters, Presley was asked about his decision to serve as a regular soldier. “I was in a funny position,” he told them. “Actually, that’s the only way it could be. People were expecting me to mess up,

to goof up in one way or another. They thought I couldn’t take it and so forth, and I was determined to go to any limits to prove otherwise, not only to the people who were wondering, but to myself.”

Most young men are changed by military service, but that change was even more marked with Elvis. In many ways, the fame that came to him when he was just 20 years old had arrested his development. He may have been 23 when he entered the army, but he was still a boy, as gauche and callow as those straight-from-home 21-year-olds he was being inducted with. The Elvis that emerged from the army was a different man, in good and bad ways. With his mother gone and the love of his life now by his side, as well as uppers coursing through his veins 24/7, the Elvis that landed back in New Jersey on 3 March 1960 wasn’t the Elvis that left. He’d matured and in the world of rock’n’roll, growing up is often a very dangerous thing to happen.