In this interview from 2020, the evergreen entertainer talked us through his early career at the epicentre of British rock’n’roll…

“I never wanted to be a singer,” says Joe Brown in a voice as redolent of London as the rev of a black cab. “I mean, you couldn’t call me a bloody singer, could you?” He clears his throat and adds,

“I can cough me way through a few songs…

“I just wanted to play my guitar,” Brown goes on. “But I got talked into singing.”

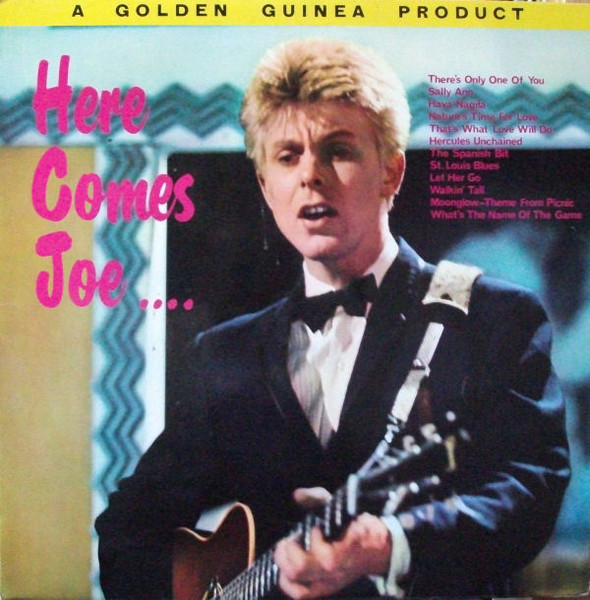

Brown, of course, is being characteristically modest. In a career stretching back to the mid-50s, the all-round entertainer has made hit records such as the near-chart-topper A Picture Of You, which reached No.2 in 1962. He’s starred in West End musicals (Charlie Girl), appeared in films (What A Crazy World and Mona Lisa), presented radio programmes, hosted three seasons of his own TV series, The Joe Brown Show, and been a guest on countless other programmes.

A mark of his enduring popularity is that, at the age of 78, he’s currently in the middle of a 79-date UK tour.

As for his singing ability, a new 6CD 60th Anniversary boxset finds him putting his stamp on material ranging from George Formby’s When I’m Cleaning Windows, to Elvis’ All Shook Up, The Who’s Pinball Wizard and Motörhead’s Ace Of Spades.

“Frightenin’, ain’t it?” he says of the variety of music he’s covered in the past six decades.

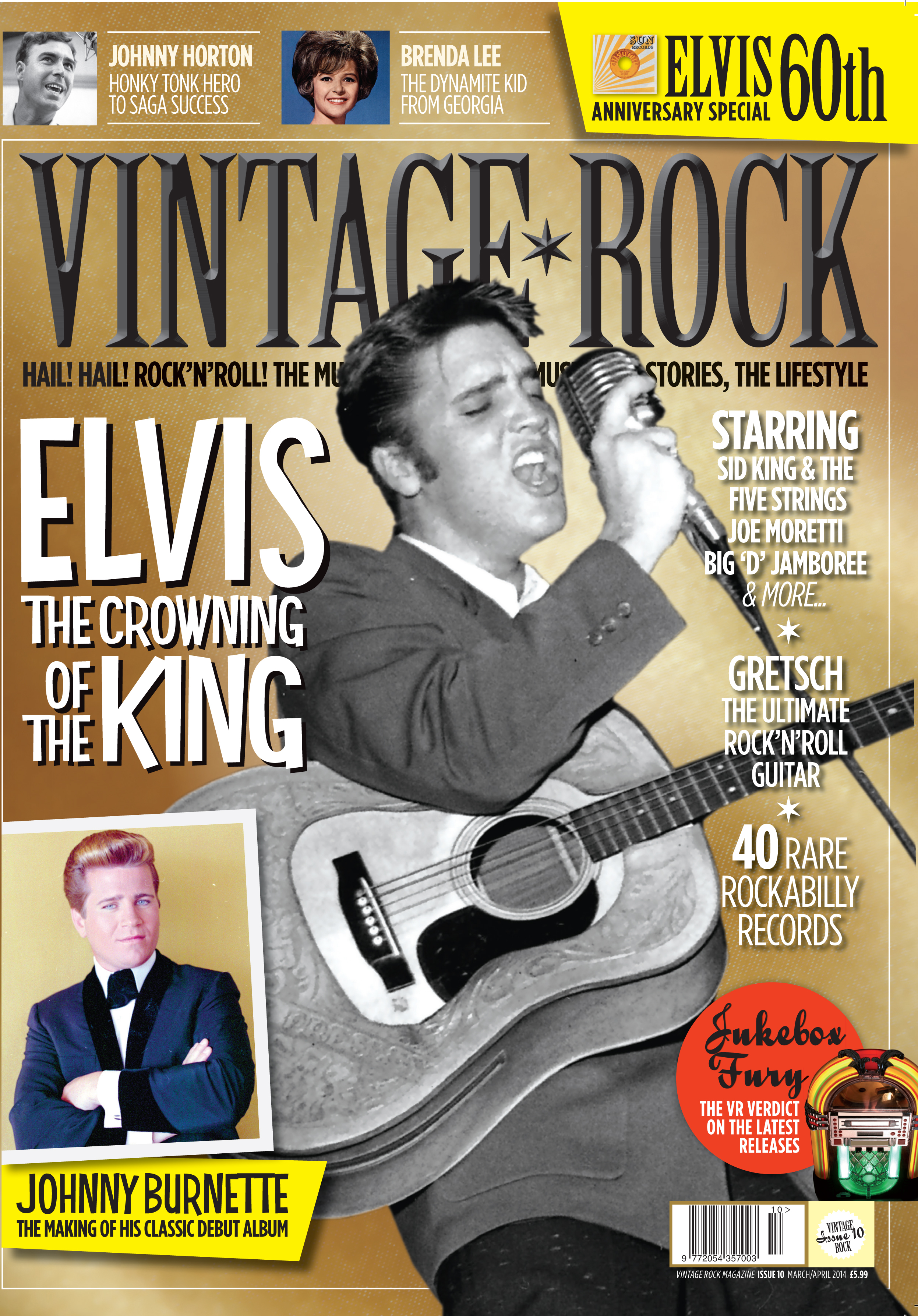

The foundation of his career, though, was rock’n’roll. At the end of the 50s, Brown played guitar for some of the biggest rock’n’roll stars on Jack Good’s groundbreaking British TV show, Boy Meets Girls, including Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran, whom he accompanied on their ill-fated UK tour in 1960.

Despite his image as a chirpy Cockney, Brown was born a long way from London, in Swarby, Lincolnshire, on 13 May, 1941. It was the middle of World War Two and at a time when other children were being evacuated out of the capital that the two-year-old Brown moved to Plaistow in East London, where his mother ran a pub called The Sultan. In the absence of Joe’s father, who died when he was young, Mrs Brown was a tough landlady who kept order by clobbering troublemakers with a sock containing two snooker balls.

“There was no one musical in my family, but there was a lot of music in the pub and I’ve recorded some of the stuff I heard there,” the singer recalls. “The first hit I ever had was Darktown Strutters’ Ball, which was an old American negro spiritual thing [first recorded in 1912]. Then I did I’m Henery The Eighth, I Am by English music hall star Harry Champion.”

Of the latter, Brown adds, “I didn’t know there was a verse! I just kept hammering away on the chorus… and nobody bloody bought it!”

It was in The Sultan that Joe fell in love with the guitar when he was 10 years old.

“I bought my first guitar off a bloke called Georgie Dance who used to play guitar in our pub. He sold it to me for a pound. Once I got it, it was never out of my hands. I very religiously tried to tune it the way he tuned it for quite a while until I found out that he had his own way of tuning it.” Brown chuckles. “So I had to start again, really. I’ve never had a lesson. I just learned what I heard.”

As a teenager, Brown formed a skiffle band with some friends who attended a local youth club. “It was called the Ace Of Clubs Rhythm Band. I remember having these cards printed and they spelt ‘rhythm’ wrong! Then I met a couple of guys from Leytonstone who had a skiffle group called The Spacemen. I joined them and we had a great time playing all around London. We played Brixton skating rink and places like that. We had a lot of gigs, because skiffle was really rife.”

At the time, he mostly just played guitar.

“But I sang some songs. When rock’n’roll hit us, I sang Buddy Holly songs, because I liked Buddy Holly. The music kind of went from skiffle into rock’n’roll. We already had the groups in Britain and we were just looking for material to play. When we heard The Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly and Elvis, everyone jumped straight on the bandwagon.”

As a schoolboy, Brown spent his weekends selling winkles and jellied eels from a barrow in the East End – he was a genuine barrow boy. When he left school, however, he needed more regular employment to support his musical career.

“I tried to do an electrician’s apprenticeship, which didn’t last long, but our washboard player in The Spacemen worked on the railway, so he got me a job and I became a fireman on the steam trains, which was wonderful.”

Train songs from Freight Train to Rock Island Line were a staple of the skiffle craze, so shovelling coal into the firebox of a speeding locomotive was the most credible day job a musician could have.

“I was kingpin because I would turn up at gigs straight from work, as black as Newgate’s knocker, wearing my fireman’s cap and greasy overalls. It was great!” Brown enthuses.

Another of Brown’s trademarks was a spiky haircut unlike any other performer’s in the late 50s. He explains how the hedgehog style came about.

“I was doing a gig at Butlins holiday camp in Farley in Yorkshire with the worst band I’ve ever played with. They were called Clay Nichols And The Blue Flames, and we were bloody awful. The kids weren’t coming into the ballroom to see us, so I said, ‘What we need is a gimmick.’ We came up with the idea that one of us had to have his head shaved every morning at the barber’s shop on the camp. I drew the short straw and had to go down there every morning. All these girls used to turn up to watch them shave my head. Then we painted a red, white and blue target on the top. When it started growing back, that’s how it grew through: straight up in the air. Before that, it was all limp and horrible.”

There weren’t many rock’n’roll guitarists in Britain at the time, so when promoter Larry Parnes needed a stand-in for a musician who had gone sick before a show in the coastal resort of Southend, he called Brown. It turned out to be his big break.

At the end of the show, TV producer Jack Good was auditioning singers for his forthcoming series, Boy Meets Girls – a follow-up to the hit show Oh Boy!. The band were asked to stay behind and back the hopefuls, and it was Brown’s playing that impressed Good the most.

“Who’s Joe’s manager?” asked Good. To which Parnes, the ever-opportunistic promoter nicknamed Parnes, Shillings & Pence, instantly replied, “I am.”

“I’d never met him before!” grins Brown, who found himself signed up on the same day by the two most influential behind-the-scenes characters in British rock’n’roll. Between Good’s TV shows and Parnes’ tours and management, the two men were responsible for launching the careers of nearly all the homegrown stars of the period, including Marty Wilde, Billy Fury and Georgie Fame. Plus Joe Brown, of course.

“Jack hired me as lead guitarist on Boy Meets Girls,” Brown marvels. “Lead guitarist – when I couldn’t read a note

of music!”

Looking back, Brown sucks his teeth and says, bitterly, “I went to Jack’s funeral [in 2017] and all the big stars that owe their careers to Jack were terribly conspicuous by their absence. PJ Proby and Shakin’ Stevens were there and that was it. Not even a bloody card, you know?” As for Parnes, who famously dreamed up the stage names Wilde, Fury et al… “He wanted to call me Elmer Twitch ’cos I was one of those very nervous kind of blokes, always twitchin’ about. I had a big row with him about it the first day I met him – but I kept me name!”

Brown’s first day on the set of Boy Meets Girls found him backing Johnny Cash, and he almost lost his job straight away. Cash was singing Five Feet High And Rising, which required Brown to play a repetitive two-note rhythm throughout. Growing bored, he improvised a twangy fill. Cash halted the recording and told him, “There’ll be no pickin’ there!”

Production costs were so high that Good fired Brown for causing the interruption, but when Cash discovered what had happened, he successfully argued for the guitarist’s reinstatement.

Later in the show’s run, Brown made his first appearance as a featured singer, performing a cover of The Avons’ hit Seven Little Girls Sitting In The Back Seat.

“People kept writing in, asking, ‘Who’s that guy at the back?’” Brown remembers. “Eventually, Jack said, ‘You’re going to sing a song this week.’ He made me sit in a horrible cardboard car with a bunch of puppets as the girls in the back. Oh dear! Why couldn’t I have sung a Chuck Berry song?”

Brown’s singing proved popular and he subsequently signed with Decca to release his first single, a ballad called People Gotta Talk, penned by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, whose many hits for others included A Teenager In Love and Save The Last Dance For Me.

The song didn’t chart, but Brown wasn’t bothered.

“I’ve never been an ambitious sort of bloke. I just take it as it comes, and I’ve been really lucky, because a lot has come my way.”

In January 1960, Brown embarked on a UK tour with Billy Fury, Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran.

It was Jack Good who came up with the idea of dressing Vincent in head-to-toe black leather, but the hard-drinking Be-Bop-A-Lula singer had no trouble living up to his menacing image. “Vincent was a dangerous man,” Brown remembers. “On the coach he’d sit in the front seat, next to the driver, waving a pistol around.

“Someone said, ‘Joe, go and take that pistol off him.’ ‘Me…?’ ‘Yeah, he likes you.’ So I went up and said, ‘You can’t do that, Gene, this is England. You can’t go waving guns around in England.’

“Gene said, ‘Oh, I don’t want to hurt you, Joe.’ So I said, ‘Give it here, then, and we’ll sort it out later.’

“I got all them jobs,” Brown continues. “Once it was a knife that I had to take off him. He was a strange one, old Gene. He was in a lot of pain, with his leg, and he drank a lot. So that was a dangerous combination: drinking and waving a pistol around. We weren’t used to that in England.”

Cochran was a calmer presence.

“Eddie taught me a lot on the guitar that I didn’t know. Some of the American guitar players tuned their guitars differently and used lighter gauge strings. I learned a lot from sitting and playing with Eddie. As did Big Jim Sullivan and a lot of us.”

The tour, of course, ended with a car crash on 17 April, 1960, that killed Cochran and seriously injured Vincent.

“That could have been me, and probably would have been, because I always travelled in the same car with them,” Brown reflects.

Shortly before the accident, however, Brown’s rockabilly update of Darktown Strutters’ Ball was starting to take off and he was taken off the Cochran/Vincent tour to headline a tour of his own.

His hits continued with Shine and What A Crazy World We’re Living In. The latter was a music hall-style Cockney knees-up, penned by Alan Klein, that inspired the film What A Crazy World in which Brown made his big screen debut, alongside Marty Wilde.

The song that catapulted him to the top, however, was A Picture Of You, a twangy, country-inflected number penned by two members of Brown’s band The Bruvvers: John Beveridge and Peter Oakman.

“I’ve known Peter since he was about 14 years old, when I joined his group, The Spacemen,” Brown chuckles, fondly. “We knew it was a good song because I did what I always did before I recorded something: I put it in the show and played it on stage. Then, about a week or two before we recorded it, I took it out of the show. That way when we went into the studio we knew it well, but it sounded fresh.”

Picture Of You spent nine weeks in the UK Top Five throughout the summer of 1962 and spent two weeks at No.2, kept off the top spot by Mike Sarne’s Come Outside.

The hits continued with It Only Took A Minute (No.6) and That’s What Love Will Do (No.3) and songs like Sally Ann, Nature’s Time For Love and a cover of With A Little Help From My Friends that kept his voice on the airwaves throughout the 60s.

Among the artists that opened for Brown at the height of his chart success were Del Shannon, Dion, The Crystals… and an upcoming group called The Beatles, who played second billing to Brown at two venues.

Unbeknownst to Brown until many years later, George Harrison sneaked into a room backstage at one of the concerts and had his photo taken posing with Brown’s guitar. In later years, Brown and Harrison became near-neighbours and close friends, with Harrison serving as best man at Brown‘s second wedding in 2000.

Harrison died the following year, and in 2002 Brown closed the all-star tribute show Concert For George with his rendition of I’ll See You In My Dreams.

Brown could easily have coasted on the nostalgia circuit but the idea of living off his old hits held no appeal for him. At the dawn of the 70s he grew long hair, a moustache and beard to form a progressive country-rock band called Brown’s Home Brew. The combo might have become Britain’s answer to The Band, but unscrupulous promoters billed the group as a Joe Brown show and the fans who turned up expecting to hear his hits were disappointed by the unfamiliar material.

Brown survived the debacle, however, and went on to establish himself as a genre-defying performer who to this day serves up a repertoire of whatever music he likes, from ukulele tunes to country hoedowns, old-time music hall songs, blues numbers and rock’n’roll. In 2009 he was awarded the MBE for his services to music.

Looking back to his roots at the birth of British rock’n’roll, Brown says, “I don’t think anyone realised how big it was gonna be. In fact, I’m sure they didn’t. When Roger Cook and I wrote a musical play about skiffle [Don’t You Rock Me Daddio in 2005], I was researching old taped interviews, and these guys were saying things like, ‘How long do you really think it’s going to last?’ They really put it down, all the time. Now it’s probably one of England’s biggest exports, the music business.”

And Joe Brown remains one of its best-loved stars.