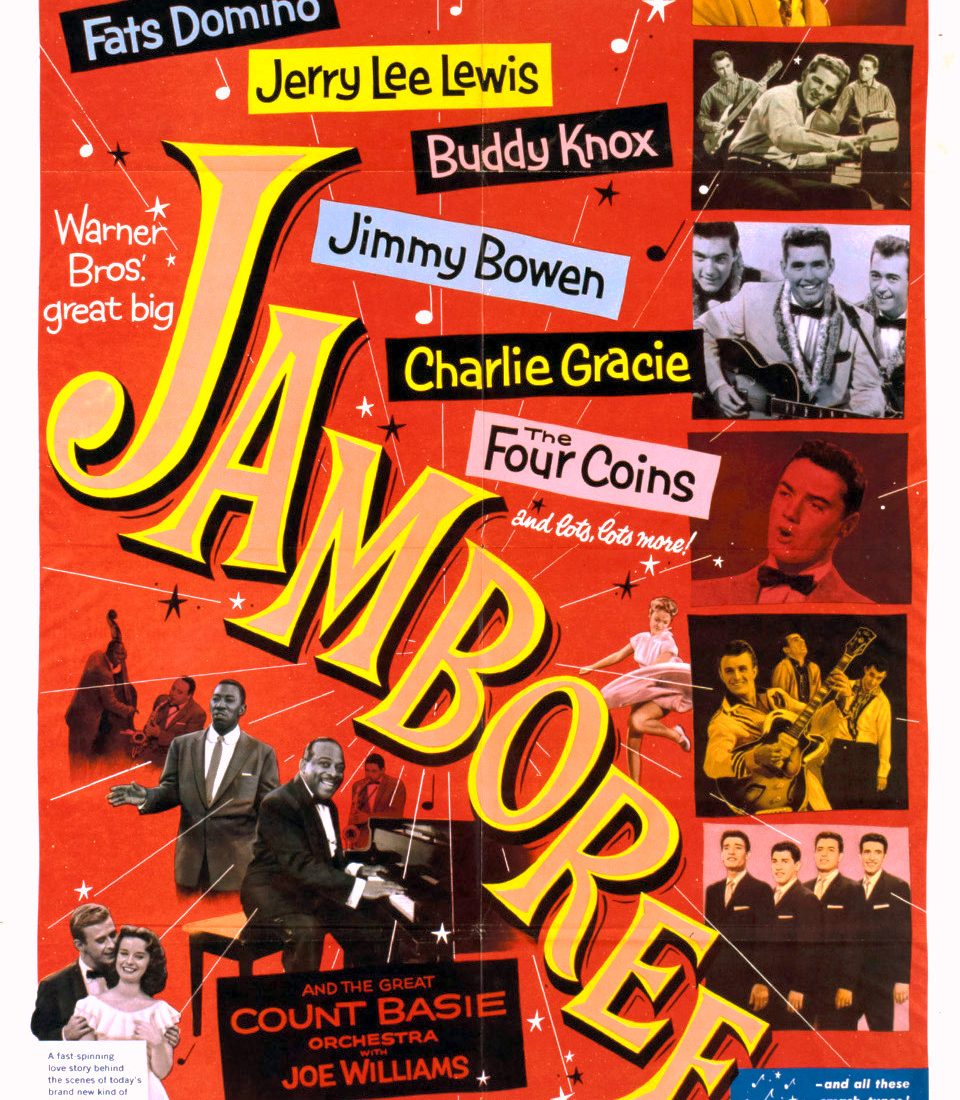

A low-budget movie designed to cash in on the emergence of rock’n’roll, Jamboree captured performances by Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, Carl Perkins, Charlie Gracie and others… By Douglas McPherson

The disc jockeys picked its stars! The disc jockeys picked its tunes! And the disc jockeys themselves are in it!” So screamed the sparkly captions to the trailer for the 1957 jukebox movie Jamboree. As clips of Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Knox, Jimmy Bowen and Charlie Gracie flashed across the screen, there was little hint that the movie was anything more than a string of musical performances.

But then, the plot that nominally linked the songs wasn’t really the point of what the trailer called “Your all-time, all-out, musical round up!”

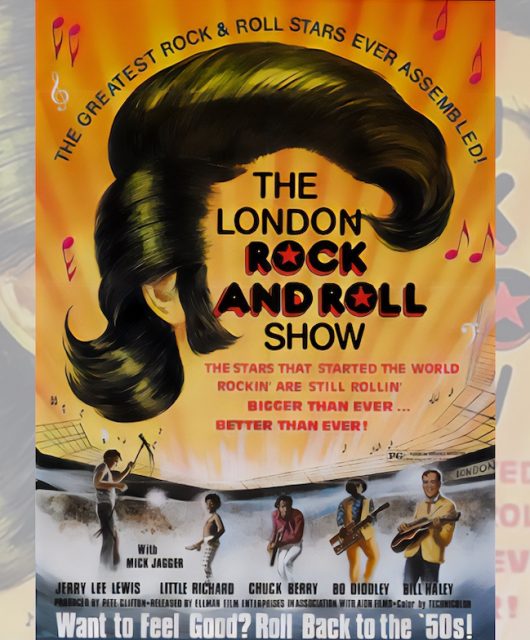

The previous year’s Bill Haley vehicle Rock Around The Clock had shown Hollywood that there was money to be made from rock’n’roll. The swift follow-up, Don’t Knock The Rock, and Rock, Rock, Rock!, which featured Chuck Berry, plus the glorious colour Jayne Mansfield movie The Girl Can’t Help It, with musical cameos by Little Richard, Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran, had made the same point.

Shot in black and white, Jamboree was Warner Brothers’ low-budget bid for a piece of the action. The film was originally slated to be called The Hit Record, and the makers, the independent production company Vanguard, hoped to feature the pioneering rock’n’roll DJ Alan Freed, who had played himself in the first three of the above movies and also starred in the 1957 flick Mister Rock’n’Roll, but negotiations with him fell through.

Instead they hit upon the idea of hiring some 18 DJs, with one each to introduce the musical stars. It was a smart move that ensured all the jocks would promote the picture in their territories throughout the United States, Canada and Europe. The number of featured presenters, meanwhile, caused the film to be titled Disc Jockey Jamboree in the UK.

The only one of the record-spinners remembered today is Dick Clark whose Philadelphia TV show American Bandstand began broadcasting nationally shortly before Jamboree’s release. The one who stands out, however, is Jocko Henderson – “the ace from outer space” as Clark calls him – who introduces Lewis Lymon And The Teenchords while wearing a spacesuit.

The story, by Leonard Kantor and Milton Subotsky, features two teenage singers, Honey Wynn (Freda Holloway in her only film role) and Pete Porter (Paul Carr), who form a successful duo only to have their managers, a former married couple played by Robert Pastene and Kay Medford, try to split them up because of their own rivalry.

Pastene was best known for playing Buck Rogers in the space hero’s first TV adaptation in 1950. Coincidentally, Carr would play a supporting role in the 1981 series of Buck Rogers In The 25th Century. Medford is the most charismatic of the actors and went on to be nominated for a Tony and an Oscar for her roles in the 60s Broadway show and film Funny Girl.

While the dramatic element is insubstantial, the leads perform a sweet ballad, Who Are We To Say, that benefits from the personable Holloway miming to the voice of Connie Francis, while Carr does his own singing.

The completely self-contained musical performances are introduced as artists recording in the same studio as the fictional couple or appearing on the same shows as them, including an extended telethon presented by Clark in aid of an unspecified “dreaded disease”.

The historical highlight is Jerry Lee Lewis’ big screen debut, performing his then new release Great Balls Of Fire. The iconic, strikingly shadowed monochrome sequence was instrumental in introducing the Ferriday Fireball to audiences in such faraway locales as Britain and Australia.

Given second billing behind Fats Domino, Lewis was a late addition to the cast, thanks to his breakthrough that summer with Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On. His inclusion was unsurprising given that GBOF’s co-writer, with Jack Hammer, was Otis Blackwell, the musical director of Jamboree.

Lewis recorded the song at Sun Records in Memphis the week before travelling to New York to film his segment and the movie uses a different take to the subsequently released single. The young Killer was nonplussed when told he had to mime the number at a fake piano, observing, “This piano ain’t got no notes!”

He did, however, finally discover how his childhood movie hero Gene Autry had managed to sing while riding a horse. “‘Ooohhh,’ I said to myself, “So that’s how he did it,’” he recalled in Rick Bragg’s biography, Jerry Lee Lewis – His Own Story.

If Lewis’ miming isn’t perfectly synced to the music, the same can be said of Fats Domino, who was equally uncomfortable with the technique. However, it’s still fun to see Fats rollicking through the sax-powered Wait And See.

Carl Perkins’ lip-syncing is more convincing on the solid mid-pace rockabilly number Glad All Over and it’s a shame his name was almost lost in the small print at the bottom of the movie poster. He should have been a headliner instead of Jimmy Bowen, who performs the limp Cross Over.

The most visually arresting scene is Charlie Gracie performing Cool Baby on a cartoon-style set that looks like the inspiration for Top Cat’s alley. Another highlight is a 17-year-old Frankie Avalon making an assured silver screen debut with the perky mover Teacher’s Pet.

Not everything was rock’n’roll, though, with the Count Basie Orchestra and country yodeller Slim Whitman thrown in for older cinema-goers.

Other non-rocking numbers were presumably included for international appeal, including Jodie Sands’ Japanese pastiche Sayonara, while Brazilian singer Cauby Peixoto appears as Ron Coby to deliver the dramatic ballad Toreador.

A low point is Buddy Knox’s tepid Hula Love. It was a No.9 hit for him in ’57, but it’s a pity he couldn’t have sung his chart-topper of that year, Party Doll.

And what did Jerry Lee think of the film?

According to his, at the time, child bride-to-be Myra in her book Great Balls Of Fire! (co-written with Murray Silver), when Lewis took her to watch Jamboree he refused to bring her into the cinema until moments before he was due on screen, and escorted her out again after his segment, saying, “There’s nothing else in it you’d wanna see.”

“But I won’t know what the movie’s about,” she protested.

“It’s about an hour an’ a half too long,” he replied.

An overly harsh judgement, perhaps. But it’s probably fair to say that this time capsule of mid-50s culture is easier to enjoy as a series of individual performances by its more rocking musical acts, filmed in their prime, than as a romantic musical viewed in its entirety.