It’s nearly 70 years since Elvis Presley found himself singing to a dog on national TV in what’s considered the nadir of his career. But was the programme’s host really out to humiliate? We look at how The Steve Allen Show tried to neuter the raw charisma of rock’n’roll’s newest star…

There are some images of Elvis that are almost sacred objects to fans. That screaming, impossibly handsome young

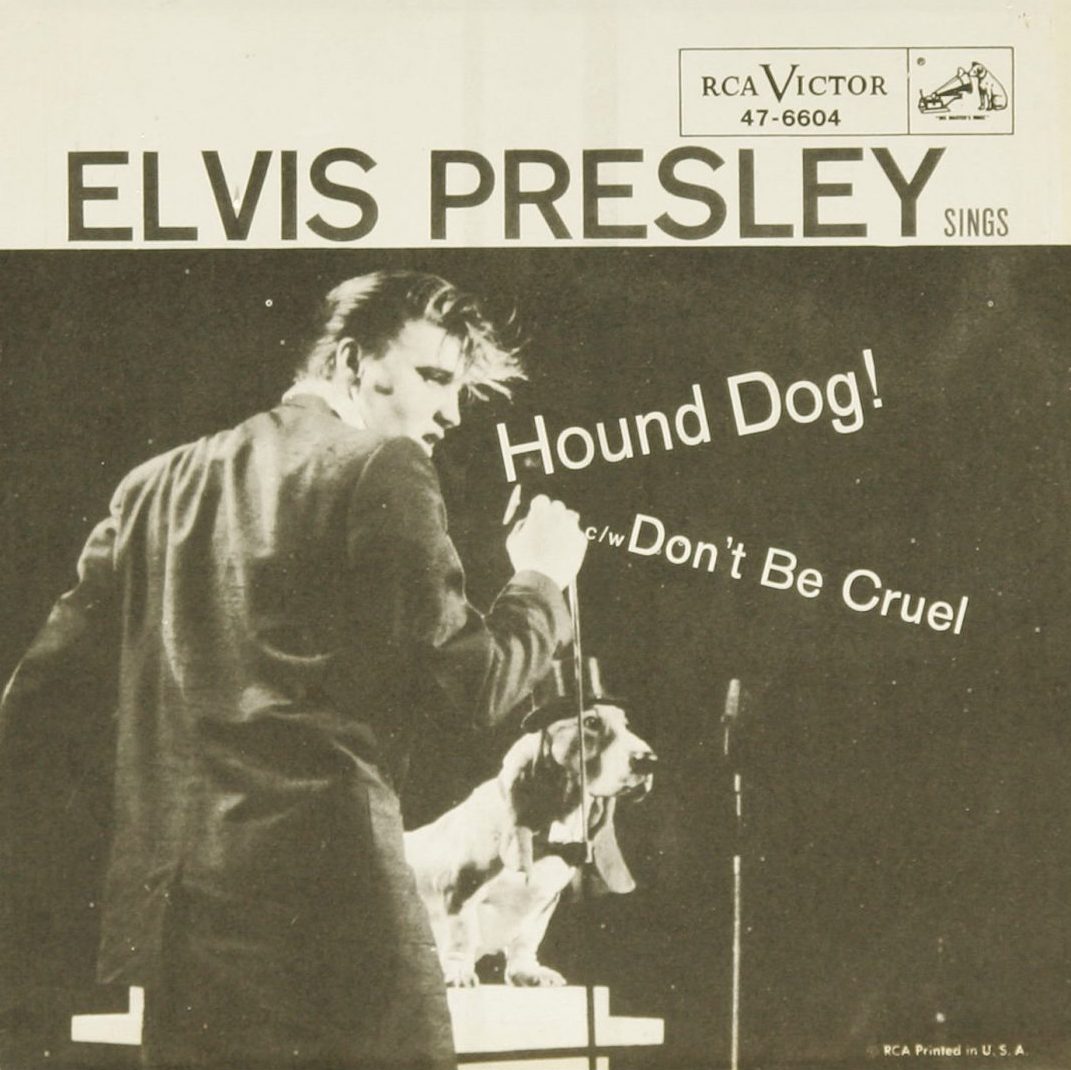

buck on the front cover of his first album is one. Andy Warhol’s triptych of Presley, gun in fist, from Flaming Star is another. But there’s one, more ignominious photo that fans would rather didn’t exist, and that’s of Elvis singing Hound Dog to a bewildered looking Basset Hound on The Steve Allen Show in 1956. And yet, in a way, no image or TV clip better captures how mainstream America sought to fight back against the raw, subversive energy of rock’n’roll.

It’s nearly 70 years ago that NBC broadcast what would become one of the most famous, nay infamous, clips of Elvis ever, one that Presley forever regretted.

He’d made his small-screen debut only six months before, on the Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey-fronted CBS variety programme Stage Show, following it up with two appearances on The Milton Berle Show. While Presley’s six turns on Stage Show and his first performance on Berle had elicited the odd tut and eye roll from Middle America, it was nothing compared to the furore after his second Milton Berle gig on 5 June 1956.

At first, everything about Elvis’ performance of Hound Dog was as expected. Yes, there were the ferocious mic gropes and jittery leg movements, but nothing that was that different or more licentious than before. Then, towards the end, Presley decided to fling himself into a half-tempo, blues-charged ‘bump and grind’ version of the song, jack-knifing his legs and gripping the microphone with an almost sexual relish. The audience absolutely loved it.

The next day, the media was screaming with apoplexy, with reviewers decrying Presley’s lusty swagger and indecent posturing. “Popular music has been sinking in this country for some years,” fumed journalist Ben Gross in The Daily News. “Now it has reached its lowest depths in the ‘grunt and groin’ antics of one Elvis Presley. The TV audience had a noxious sampling of it on The Milton Berle Show the other evening. Elvis, who rotates his pelvis, was appalling musically. Also, he gave an exhibition that was suggestive and vulgar, tinged with the kind of animalism that should be confined to dives and bordellos.”

Sometimes, it’s hard to look back and be able to fully grasp how shocking a cultural moment might have been in the long-distant past, but, watching that performance in 2021, it’s staggering how potent and electrifying it still is. It’s as if all of the imagined threat of rock’n’roll is boiled down to that set-closing 54 seconds. When you consider how beige and sexless American television – and indeed culture – was at the time, that libidinous, down-tempo version of Hound Dog seems like it’s been beamed in from another planet.

The storm it stirred was unlike anything Elvis had yet encountered. Presley’s press, up to that point, had been fairly positive, but now the knives were out. To the press and the pulpit, Elvis represented the worst excesses of juvenile delinquency and godlessness. Unlike other rock’n’rollers, who revelled in their outlaw status, the Pentecostal-raised Elvis seemed rattled at first by being the poster boy for bad behaviour. “I don’t do any vulgar moves,” he said to reporter Aline Mosby, while telling another writer, “I’m not trying to be sexy.”

Elvis had been booked for The Steve Allen Show since before that second Berle appearance, but with all the media brouhaha around him, NBC were under pressure to strike him from the guest list. “As of now he is still booked for July 1,” Allen said on The Tonight Show, “but I have not come to a final decision. If he does appear, you can rest assured that I will not allow him to do anything that will offend anyone.”

One columnist, Charles Mercer, even penned an open letter to Allen, pressuring him to drop this new upstart from the line-up: “My argument against his appearance is simply lack of talent. I can’t for the life of me see why you want to have such an untalented guy on your programme.”

Less than a week later, Allen responded in print. “Who is to say that Elvis has no talent?” he countered. “You may say it, and a few million other people might be found to support you, but I am sure that additional millions will rise to his defence and say that he has oodles of talent… When I was a teenager, all the adults I knew told me Frank Sinatra had no talent. Later, I’ve heard that Vaughn Monroe had no talent, that Liberace has no talent. I’m sure the point is obvious.”

Allen made it clear that he intended to keep Presley’s urges under control.

“He thoughtlessly indulged in certain dance movements on his last TV appearance which a number of people thought objectionable,” he wrote. “He knows he made a mistake with the Milton Berle business and I think he’s smart enough not to do it again… So the thing to do, it seems to me, is to allow him to appear on television any time he wants, but to make certain that he conducts himself in a gentlemanly manner, and that is precisely my intention.”

NBC were quick to reassure doubters that Allen would be spotlighting a new “revamped, purified and somewhat abridged Elvis Presley.” The network, it seemed, was taking no chances. Elvis was told he would be bedecked in a white tie and tails and would have to play down, if not eradicate entirely, the hip thrusts. The irony was that NBC were hungry to have Presley as a guest to capitalise on the singer’s new-found notoriety, and to hopefully batter rival programme The Ed Sullivan Show in the ratings, yet they didn’t want the very quality that had excited viewers in the first place.

Elvis arrived at NBC’s New York City rehearsal studio on 29 June, accompanied by a photographer hired by Presley’s record company RCA, Al Wertheimer. The young snapper recalled that Allen eyed Presley “much as an eagle does a piece of meat”, before one of the presenter’s secretaries ushered Elvis to be measured for his new suit.

The broadcast was scheduled for the coming Sunday, with Presley arriving at the Hudson Theatre on 44th Street early in the morning. The itinerary was a full day of rehearsals, before the live show in the evening. Elvis was down to perform two songs and take part in a comedy skit, alongside Allen and fellow guests Andy Griffith and Imogene Coca. Clad in his white tie and tails, Elvis discovered he’d be performing on a Greek-columned set (Allen was amused by the idea of presenting what he considered low culture in a high-culture setting). Wertheimer recalled that, in the dress rehearsals, Elvis “sang without passion. He didn’t move, didn’t touch the microphone, he stood square, both feet spread, and stuck to the ground.”

After Elvis finished the run-through of I Want You, I Need You, I Love You, Allen walked up to him, patted him on the back and muttered, “That was great”. Elvis smiled and replied, “Thank you, Mr Allen.”

Then came the moment he’d been dreading. Having Elvis sing Hound Dog to, well, an actual dog was one way to make sure he didn’t turn the song into the carnal come-on he had on Milton Berle’s show, but it also fitted The Steve Allen Show’s comic template. With the dog also gussied up in a collar, bow tie and top hat, it looked at first that the gimmick was falling flat. As Presley serenaded the hound, the dog looked everywhere but towards Elvis. Allen suggested “that they get to know each other”, and so Presley began to ruffle its fur. Eventually, the two bonded enough for the dog to do what was expected of it, at which point the assembled stagehands burst into applause.

For the live show, there was no way, it seems, that Elvis could be introduced without Allen acknowledging the storm around his appearance. “A couple of weeks ago on The Milton Berle Show,” Allen said in his opening monologue, “our next guest, Elvis Presley, received a great deal of attention, which some people seem to interpret one way and some others interpret it another. Naturally, it’s our intention to do nothing but a good show,” At that point, there came a yelping sound from backstage.

“Somebody is barking back there,” he continued. “We want to do a show that the whole family can watch and enjoy, and we always do, and tonight we’re presenting Elvis in his, what you might call his first comeback… And at this time it gives me extreme pleasure to introduce the new Elvis Presley. Here he is!” Elvis then sauntered on, guitar in hand, looking noticeably less relaxed than he was for his last TV appearance, only two weeks before. Primped up as if he was about to go on stage with the Royal Philharmonic, he was the model of Southern politeness to his host.

“It’s not often I get to wear the, uh, suit and tails,” Elvis said, bashfully. “But, uh, I think I have something tonight that’s not quite correct for evening wear.”

“Not quite correct? What’s that, Elvis?”

“Blue suede shoes,” he cracked, and the audience hollered. Allen then produced “a giant petition”, featuring over 18,000 signatures from “loyal fans” who wanted to see Elvis

on TV again.

“That’s wonderful, Mr Allen, and I want to thank all those wonderful folks and I’d like to thank you, too.”

And with that, Elvis launched into his first song. Of course, there was little room to be suggestive on a track as inherently inoffensive as I Want You, I Need You, I Love You, and indeed Elvis appeared less stilted during this number. It was only with the next song that Presley began to feel the waves of shame.

“Elvis, your new record hit, I predict it’s going to be one because I’ve heard you rehearse it and you’re going to record it tomorrow. It’s called Hound Dog, and I’ve got you a very cute little hound dog right here,” Allen said as the camera closed in on the lugubrious-looking Basset Hound in a dignity-challenging top hat. Allen then exited the stage as Elvis cupped the dog’s chin, before turning to the audience as if to say, ‘we’re all in this together’ As dog performances go, the unnamed hound was never likely to scoop an Oscar, but she didn’t shame herself either. She didn’t amble off or bite anyone, even if she often looked as though she’d rather be anywhere else but on that stage in front of the cameras.

All told, those two minutes may have been the nadir of Elvis’ TV life, but, ever the pro, he never gave away quite how demeaning it must have been. “He always did the best he could with whatever situation he was given,” remembered Jordanaire Gordon Stroker about that famous night, “and he never, ever insulted anybody.”

It’s worth remembering how old Elvis was here. Aged 21 and with just six months of TV appearances behind him, he was still easily cowed by older, more experienced types. Allen was 35 and, even by then, an industry veteran. Had it been two years later, it’s doubtful Presley would have capitulated so easily or looked so diffident in those awkward exchanges with his host.

That shyness was even more evident in the comedy skit, dubbed the ‘Range Roundup’ sketch. Elvis hadn’t yet lensed his first movie, and again, it’s difficult to imagine Presley sinking into the shadows this much had the sketch been made in ’58 or ’59.

Elvis spent the first two minutes or so lurking timorously in the background, his get-up presciently close to what he’d be sporting in his first feature film later that year. At first, he confined himself mostly to mouthing lines inaudibly in the background, but warmed up when his character, Tumbleweed, was ushered up to the front by Allen. By the end, he was more in his comfort zone, strumming along to some featherweight Wild West ditty and then, in the final moments, getting his own self-mocking solo: “Well, I got a horse, and I got a gun,” he sang, “And I’m gonna go out and have some fun/ I’m a-warnin’ you, galoots/ Don’t step on my blue suede boots.”

Backstage, everyone seemed happy at how Elvis had conducted himself. On his way back to his dressing room, a man from the William Morris agency whispered, “You did a marvellous job, we really ought to get

a good reaction to this one.”

Except they didn’t – not from Elvis’ most devout followers anyway. When the singer arrived at the RCA building the next day, he was confronted by fans carrying picket signs that read ‘We want the real Elvis’ and ‘We want the gyrating Elvis’. Yet RCA seemed happy with this neutered version and appeared indifferent to those who feared the raw, sexualised Presley was gone forever. When Hound Dog was eventually released as a 45, it was issued with a cover photo from that Steve Allen Show performance, showing Elvis standing, mic in hand, with that by now famous hound to his right.

When the history of Elvis on television is written, Steve Allen is habitually cast as the villain of the piece, a middle-aged, white-bread square who took it on himself to defang Presley. But is that fair? Allen was certainly no fan of Elvis the performer, but then, as a short-back-and-sides, suit-wearing thirty-something, he wasn’t exactly the King’s natural demographic. “The reason I booked him,” he reflected, “[is that] I recognised right away that he had something. A cuteness, chiefly his face, but a beautiful sound, he never really had.”

While Allen was largely graceful towards the King in the decades after, the same couldn’t be said for Elvis. Though he’d started off by claiming he’d “really enjoyed” the show, he later told Parade he’d been made to “stand like a biddy”. Later, in 1972, he lambasted Allen for being “as funny as a crutch” and, two years later, said, “Steve Allen had me on his show… He had me dressed in a tuxedo, singing to a little fat dog. I love him for it, but I will never forgive him.”

“It was humiliating,” Elvis’ later wife Priscilla said in the 2018 documentary The Searcher. “After that, he didn’t like

Steve Allen at all.”

Elvis never appeared on The Steve Allen Show again. Though Allen was keen for a repeat performance, The Ed Sullivan Show made the King a more lucrative offer, while promising they wouldn’t be constricting him like Allen had. And thankfully, it’s these performances that have lingered longer in the cultural memory than Elvis singing Hound Dog to a baffled-looking canine.

By the time Elvis had completed the third of his three appearances on Sullivan’s show, any fears that he’d been permanently emasculated had been laid to rest. His reputation was, by now, sealed forever.