In our series looking at rock’n’roll artists who just missed out on the big time, we remember the underrated talents of Wee Willie Harris, one of the British scene’s earliest stars. By Jack Watkins

Who was the greatest early British rock’n’roller? It’s a question guaranteed to divide opinion. Billy Fury’s stock is very high these days, but Terry Dene seems forgotten. Tommy Steele and Cliff Richard made historically significant recordings, while Marty Wilde, with his great range, remains a live performance marvel to this day.

It wasn’t Lonnie Donegan, whatever the revisionists claim. He was the unchallenged King Of Skiffle, but for all his energy, he was not a rocker. And, despite the genre-defining brilliance of Brand New Cadillac, it wasn’t Vince Taylor, who couldn’t hit a note with an eight-pound sledgehammer.

Wee Willie Harris never enjoyed great record sales, but there are grounds for calling him the most underrated of Britain’s first-generation rockers. If your taste is for the grittier-voiced, piano and R&B end of the market, rather than a Larry Parnes-type pretty boy, he could be the one for you. His best songs showcase his memorably rasping tones, as well as his zany sense of humour.

Harris has an ear for the blues, showcased by his zippy versions of Bloodshot Eyes and Lollipop Mama but, without stretching the point too far, if you close your eyes and listen hard you might detect a touch of Eddie Cochran with a London twang. However, at 5ft 6in, with a cherubic-yet-impish face, this “small ball of fire,” as Harris describes himself, didn’t have the looks or physique of the prototype teen rocker.

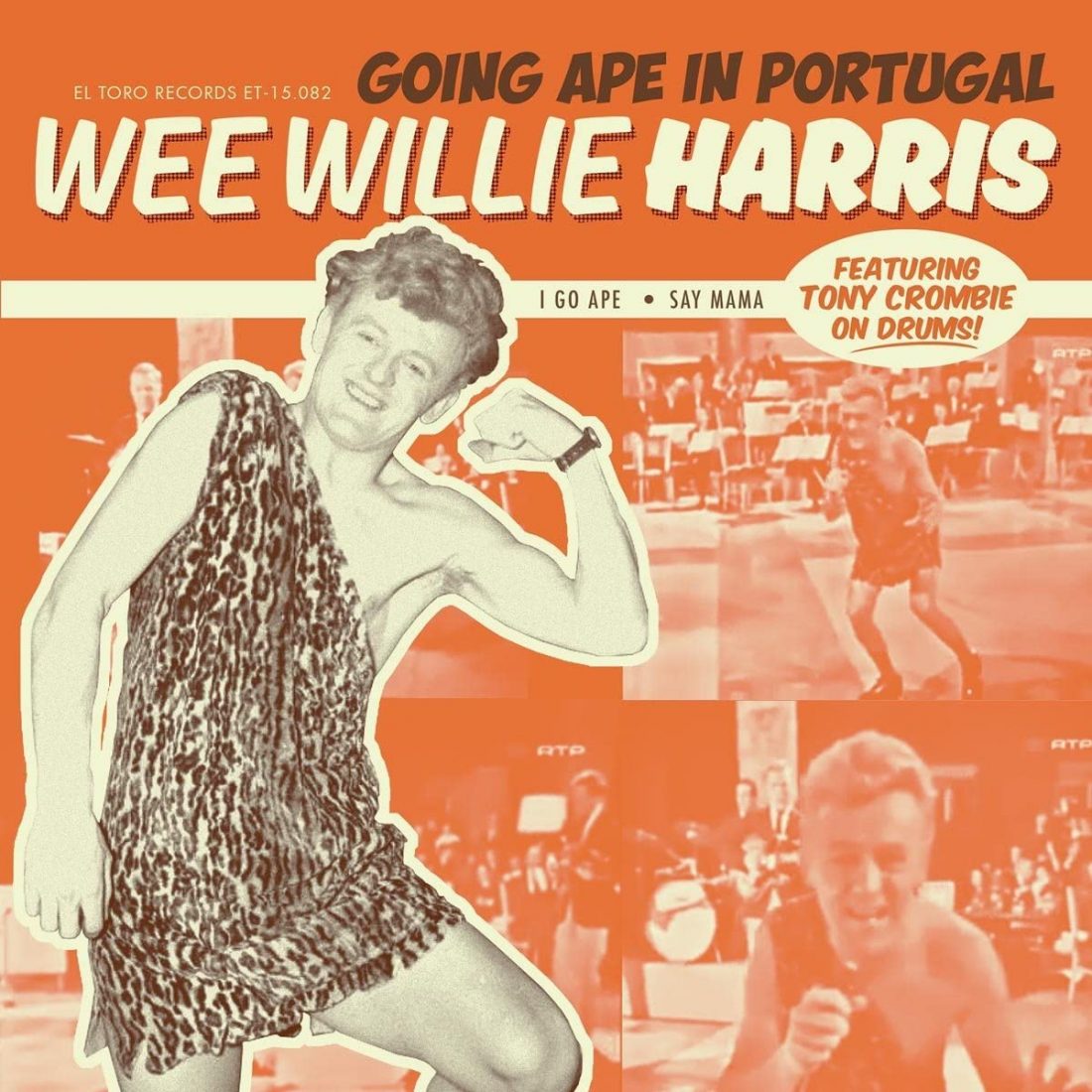

To make up for it, he took to the boards with hair dyed pink, or sometimes orange or green, depending on his fancy. He wore a big polka-dot bow tie, Teddy Boy drape, peg trousers, pink socks and crepes. On the back of the drape, his name was printed large, in the unlikely event that you mistook him for someone else. In later years, he sometimes appeared in a leopard skin suit.

Harris has always seen the fun side of rock’n’roll, leaping about and fooling around on his piano, and in his late-50s heyday he was billed as ‘Britain’s Wild Man Of Rock’. As he said: “To me, this game has always been about more than singing rock’n’roll – it’s entertainment.” But, as the years passed, the clowning began to dominate his act more and more. It was good for business, but it did nothing for his reputation with the music critics and increasingly serious-minded rock fans.

There are old clips of Harris on YouTube that look a little corny now. In any case, some people have always struggled with British rock’n’roll’s refusal to take itself too seriously, and the way many of its performers lack the cool, instinctive style of their American equivalents. But it is part of a British entertainment tradition that dates back to the age of the music halls, leading down through Donegan and Steele, to glam rock and aspects of Britpop. Wee Willie Harris is a part of that tradition.

Ian Dury was another. He loved Harris, referring to him in his 1979 hit Reasons To Be Cheerful, Pt 3. One time, when Harris visited Dury in his dressing room after a show at the Hammersmith Odeon, a delighted Dury sang him all the words to his most famous song, Rockin’ At The Two I’s. A thrilled Harris later responded by cutting an album called Twenty Reasons To Be Cheerful. In 1998, quizzed about his own part in the creation of glam rock, David Bowie stated in a 1998 online livechat: “Wee Willie Harris started glam. And I’m not joking.”

According to Rob Finnis’ biography, I Go Ape! The Wee Willie Harris Story, published in 2018, questions were raised in Parliament on the impact of Harris’ appearance and antics on the nation’s youth when he was first introduced to the mainstream press in 1957.

One distressed scribe likened his performances to that of “an exploding Catherine wheel, emitting growls, squeals, and what sounds like severe hiccupping.” Top comic Benny Hill jumped on the bandwagon, concocting a thick-wigged send-up character for his TV show named Wee Willie Hill.

Harris was not exactly Sid Vicious, and some just wondered if he was mocking rock’n’roll, but Britain was easily shocked in the late 50s. However, Charles William Harris, born in Bermondsey, south London, in 1933, the son of a Thames bargeman, was a few years senior to his fellow early British rockers and his voice had a pleasing maturity to it.

As Finnis writes in I Go Ape!, everyone who worked with Harris around that time, “recognised that Willie’s powerful, guttural voice and natural feel for American rock’n’roll stood out amongst the unconvincing Elvis and Lonnie Donegan impersonators.”

Learning to play piano by ear, Harris’ inspirations included the boogie-woogie maestros Pete Johnson and Meade Lux Lewis, as well as Fats Domino. At early performances in dockside pubs he’d do serviceable impressions of Al Jolson and Johnnie Ray.

Around 1955, he walked into a small recording studio in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex. Accompanying himself on piano, he cut a demo of the old American folk song Frankie And Johnnie, which had been a feature part of his turns. That off-the-cuff recording illustrates his instinctive skills. Enjoying success in talent contests, and with the advent of rock’n’roll enabling him to add to his repertoire, the news that fellow Bermondsey boy Tommy Steele was making a splash in the West End was enough to persuade him to head north of the Thames himself.

As well as singing with Rory Blackwell And The Blackjacks, Harris became an interval act at Soho clubs, for a time calling himself Steve Murray. He could play skiffle, rock’n’roll and more jazzy material, depending on the audience, but Paul Lincoln, owner of the legendary 2i’s club, while impressed by his voice, noticed he wasn’t getting much attention. When he told him, “You need a gimmick, something that will get you noticed,” the radical image change and new stage name, Wee Willie Harris, quickly followed.

Alongside the media attention, shows with Terry Dene and Chas McDevitt were rapturously received, and he starred in the BBC’s Six-Five Special.

By the end of 1957, Harris was signed to Decca, his first single arriving just after Christmas. This featured Rockin’ At The Two I’s, a Harris original, with B-side Back To School Again, both taken from Harris’ first Decca recording session cut before an invited audience to simulate a live club feel, the details of which are fascinatingly recounted in the Finnis biography.

Pete Frame in The Restless Generation describes Rockin’ At The Two I’s as “a silly trifle of a song, with a quasi-Fats Domino intro and a catchy chorus.” It certainly isn’t Heartbreak Hotel, and Harris complained about being saddled with “an 18-piece band doing rock’n’roll” by producer Dick Rowe.

Yet the jokey, singalong vibe captures an essential aspect of the Harris schtick. His gravelly London voice is right on it, and there are very English references to making tea and catching a number 54 bus. Arguably the trombone wasn’t a great idea, but the back beat, possibly headed by Tony Crombie on drums, certainly is. Despite sounding well over age, Harris ripped through Back To School Again, creating a superior version to the American original by Timmie Rogers.

If you like both sides of that single, which sold well enough without charting, you’ll likely enjoy all of Harris’ subsequent Decca material. Love Bug Crawl was another killer cover of an American teen rocker, although there was nothing juvenile about Harris’ vocal, even with his hint of a hiccup. His take on The Robins’ Riot In Cell Block No.9, put out on a fine, now very collectable EP, Rockin’ With Wee Willie, was majestic.

Later on, Harris would build followings in Italy and Israel, while releasing the occasional gem such as his version of Neil Sedaka’s I Go Ape!, backed with as good a reading of the old blues favourite Trouble In Mind as you’ll hear. He never did have a hit, although there was an unsuccessful Twitter campaign in 2013 to get him one via Got A Match, a novelty number on which he didn’t even play piano. Up until the pandemic he was still performing, one of British rock’n’roll’s most unforgettable voices.