After turning his back on rock’n’roll to spread the word of God, Little Richard made a dramatic return in the early 60s. Randy Fox celebrates the second coming of His Majesty…

In the early 60s, Little Richard was at the second major crossroads of his life. In 1958 he had made the decision to walk away from money, fame and rock’n’roll to pursue a life in the ministry with his Little Richard Evangelistic Team. He was primarily faithful to his promise – attending seminary school, forming an evangelical crusade, preaching sermons and recording gospel music for a variety of record labels. In 1962 he accepted an offer to tour the UK under the assumption he would perform only gospel. His attitude quickly changed once he found himself in competition with soul music heartthrob Sam Cooke on the same tour, and after he witnessed the eagerness of British audiences for rock’n’roll.

In October 1963, he returned to the UK fully prepared to rock the house, but kept the nature of the tour a secret from his family. After five weeks of touring with the Everly Brothers, Bo Diddley, and a new British group, The Rolling Stones, Little Richard closed out the tour with a triumphant performance at Granada Television’s Manchester studio, whipping the audience of British teens and Teddy Boys into an excited frenzy.

Little Richard headed back to the States and within a few weeks he chose his path. The “true” King of Rock’n’Roll was ready to make his return. The first step was a call to his old boss, Art Rupe at Specialty Records.

Tiring of the music business, Rupe had effectively quit producing new music for Specialty Records in 1960, releasing only reissues of older material. He agreed to restart the label for one more single at Little Richard’s request. In May 1964, Little Richard returned to the studio with a band, including Glen Willings on guitar, Earl Palmer on drums, and former Specialty stars Don & Dewey (Don “Sugarcane” Harris and Dewey Terry) on bass and guitar. The resulting single, Bama Lama Bama Loo, was a frantic return to the spirit of Little Richard’s 50s hits, while also updating sonic form by exchanging honking saxophones for hot electric guitars. Little Richard was confident the single would take him roaring up the charts.

Unfortunately, just as the single was released in April 1964, the US radio waves were conquered by The Beatles and a host of other British rockers – the same musicians in awe of Little Richard during his UK tours. Bama Lama Bama Loo struggled to No.82 on both the R&B and pop charts. Ironically, it fared better in the UK, rising to No.20. Despite its anemic domestic performance, an offer from Vee-Jay Records meant Little Richard was determined to try again.

Back in business

Founded in 1953, Vee-Jay Records was one of a handful of African-American owned record labels during the 50s. Scoring big with a string of blues, R&B, and rock’n’roll hits, Vee-Jay became one of the largest independent labels in the US by the beginning of the 60s – racking up big hits with acts like the Four Seasons and Jerry Butler, and securing the US rights to the first Beatles album. Despite huge successes, the label was on hard times by 1964. Little Richard had no knowledge of the behind the scenes financial problems and was eager and excited about recording rock’n’roll again.

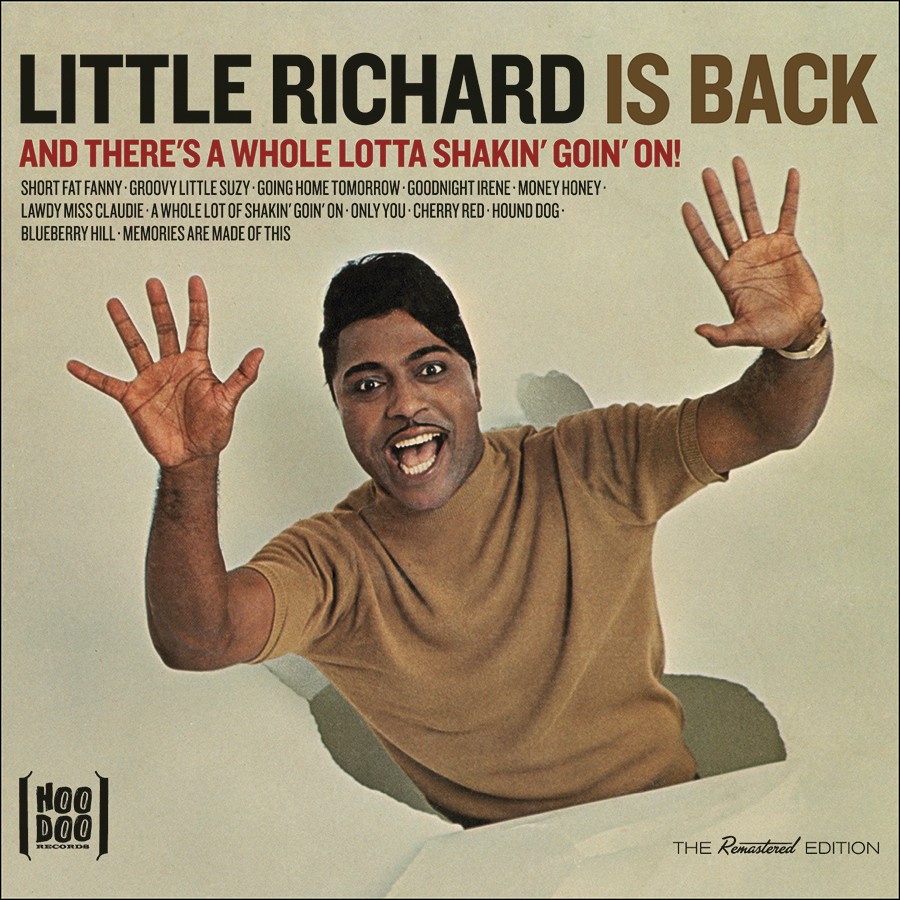

In June 1964, he cut 12 songs for his first Vee-Jay album, Little Richard Is Back (And There’s A Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On!). Released in August 1964, the album crackles and sparks with the same exuberant and flamboyant energy that marked the best of Little Richard’s Specialty recordings. Opening with an evangelical rock’n’roll altar call referencing his recent British tour, Little Richard launches a blistering version of Jerry Lee Lewis’ hit Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On. He then follows with 10 more sizzling covers of songs made famous by other rock’n’rollers and one new song – Groovy Little Suzy by John Marascalco and tunesmith Harry Nilsson. It added up to one of the most exciting rock’n’roll albums of 1964.

However, rock’n’roll excitement alone did not guarantee success in the crazy first year of the British Invasion. US teens were in the grip of British beat fever and Motown pop soul mojo. They had little interest in a “has been” star singing songs from the past, no matter the excitement level. Vee-Jay’s managerial chaos and lack of promotional resources added to the problem, and the album found little audience outside of Little Richard’s loyal fans.

One sign of Vee-Jay’s poor decisions arrived in January 1965 with the release of Little Richard’s Greatest Hits.

It was a standard record label practice to have an artist re-record their old hits the minute they signed with a new label. The goal was to get product on the shelves as quickly as possible and then focus on scoring new hits. Vee-Jay had skipped that first step with Little Richard, but now they were taking a herky-jerky step backwards instead of looking for new material and potential hits.

Recorded in November and December 1964 with assistance from Little Richard’s friend and fellow rock’n’roll wildman Esquerita on piano, Little Richard’s hoarse vocals were plainly evident, a side effect from his constant touring during the latter portion of 1964. Despite that problem, some of the hastily recorded remakes popped with energy and verve, but re-visiting past glories instead of creating new ones was plainly the wrong course.

Between January and May 1965, Little Richard returned to studio several times, cutting new material for Vee-Jay and demonstrating a focused effort update his sound. Because of the chaos at Vee-Jay much of this material sat unreleased for months or even years.

One highlight appeared in October 1965. I Don’t Know What You’ve Got But It’s Got Me – Parts I & 2 was a brilliant slice of deep Southern soul stretching across two sides of a 45. Written by soul star Don Covay and featuring beautiful, bluesy guitar work from a young Jimi Hendrix (billing himself as “Maurice James”), the single hit No.12 on the soul chart and crossed over to No.92 on Billboard’s Hot 100.

While Little Richard had returned to the charts, a strong follow-up was in order. Instead, he soon lacked a contract courtesy of Vee-Jay’s ongoing financial problems and eventual bankruptcy. Signing with Modern Records

in December 1965, Little Richard was still burning bright on the concert trail and in the studio, but there was little hope of success at Modern.

Launched in Los Angeles in 1945, Modern Records was one of the major R&B labels of the 50s, scoring big hits by BB King, Etta James, the Flairs and others. By 1965 Modern’s days as a hit maker were in the rearview mirror. The majority of the label’s business was low-cost LPs for the bargain bin market. Even though Modern released three outstanding singles by Little Richard in 1966, their main goal was recording enough new material to release bargain-priced albums to be sold at discount stores, drugstores, and corner markets.

Little Richard’s first Modern album, The Incredible Little Richard Sings His Greatest Hits – Live! was released in 1966 and fit the bill perfectly. Drawn from several nights of live recordings at the Domino Club in Atlanta, Georgia, along with one studio track, it was recorded quickly and cheaply with overdubbed applause to pump up the energy. Despite the low-rent production, Little Richard delivered

a live set full of excitement.

The second Modern LP, The Wild And Frantic Little Richard, didn’t appear until December 1967, almost a year after Little Richard left Modern. While it’s a mixed bag, it’s another example of Little Richard’s talent and charisma triumphing over so-so material and lacklustre production. The album combined left over live material from the Domino Club recordings with several hot studio tracks cut at Sam Phillips Recording Studio in Memphis, like the Sam the Sham-style novelty tune Holy Mackerel and the self-aggrandising rocker, I’m Back.

Ultimately, Modern considered its association with Little Richard a success as various reissues of both albums populated bargain bins well into the 80s. When Modern’s contract ran out at the end of 1966, Little Richard received an offer from OKeh Records, thanks largely to the efforts of his old friend and Specialty labelmate, Larry Williams. Williams began his career in the late 50s as a Little Richard-style rocker with a string of hits on Specialty. However, a 1960 drug dealing conviction brought his career to a halt, but after serving three years in prison, he returned to music, teamed up with guitarist Johnny “Guitar” Watson and was enjoying a moderate comeback on OKeh Records.

Soul lotta love

Little Richard’s OKeh recordings proved to be an artistic game changer. OKeh was a subsidiary of Columbia Records, the largest record label in the US. With more money and promotional resources behind him, Little Richard had a new opportunity to adapt his music to the modern rock and soul sounds dominating the charts.

As producer, Williams put together a crack band, including Watson and two longtime members of Little Richard’s road band – Glen Willings on guitar and Eddie Fletcher on bass. On 5 February 1966, the assembled group cut Poor Dog (Who Can’t Wag His Own Tail). Written by Williams and Watson for Little Richard, the brassy, horn-driven soul stomper was a perfect fusion of mid-60s soul “SOCK!” and Little Richard’s rock-powered “POW!”

Released in June 1966, Poor Dog (Who Can’t Wag His Own Tail) was paired with Well All Right, a supercharged rewrite of Sam Cooke’s It’s All Right. Cash Box (magazine) picked the single as a “Best Bet” and described it as a, “thumping, soulfilled, shouting tune.” Quickly picking up airplay in several regional markets, it entered the R&B chart in late August, rising to No.41. In late August, Little Richard, Williams and the band returned to Columbia’s Studio “D” in Los Angeles to cut tracks for an album. Recorded in three sessions, 30 August, 2 September and 15 September 1966, The Explosive Little Richard hit the racks in January 1967.

Opening with a smokin’ cover of Bobby Marchan’s Get Down With It, the album winds through 10 more tracks, mixing blistering, Little Richard-fied covers of big rock and soul hits (Land Of A Thousand Dances, Money (That’s What I Want) and Function At The Junction) with new songs perfectly matched with Little Richard’s strengths as both a rocker (I Don’t Want To Discuss It and I Need Love) and as soul balladeer (The Commandments Of Love and Never Gonna Let You Go). The album was focused and unified, showcasing Little Richard’s talents, charisma and personality in a way never before captured on one long player.

Despite the artistic triumph of The Explosive Little Richard, the album’s sales fizzled, and OKeh considered returning to the tried and true method of re-recording hits. Fortunately, Larry Williams’ presence at the production board yielded a slightly different approach. Williams added organist Billy Preston to the studio band at Columbia’s Studio “D” as well as a small audience. On 25 January 1967, Little Richard tore through a blistering live set of several of his Specialty recordings and a few new songs. Imaginative liner notes from KGFJ-Los Angeles DJ Jim “Doctor Soul” Witter discussing the ambiance of the imaginary “Club OKeh,” were added to complete the illusion of a hot and frantic set delivered in a LA club, and the album was released as Little Richard’s Greatest Hits Recorded Live in July 1967.

Reviewing the album in Rolling Stone, Ken Harris called it “…one of the few really exciting live rock and roll recordings on the market today.” Fans responded, making it the first Little Richard album to chart since his 1957 debut LP – hitting No.28 in the UK.

Despite the moderate sale success, OKeh dropped Little Richard’s contract in late 1967.Years later, after an acrimonious falling out with Larry Williams, Little Richard had few kind words about his OKeh recordings.

In Charles White’s book, The Life And Times Of Little Richard: The Quasar Of Rock, Little Richard claimed that he “tore up” his OKeh contract and said: “Larry Williams was the worst producer in the world. He wanted

me to copy Motown and I was no Motown artist. They made me use their band, which was all trumpets. It got so I wanted to throw all the trumpets in the world in the river.”

Despite his disdain for the horn-powered soul sound of his OKeh recordings, Little Richard displayed no aversion to brass immediately after working with Larry Williams. In September 1967, the singer signed a one year contract with soul label Brunswick Records. The three singles he recorded over the next year doubled down on his commitment to the funk-soul sound with horn sections fully deployed on hot numbers like Try Some Of Mine, Soul Train and Can I Count On You.

None of Little Richard’s Brunswick singles cracked the charts, and he again found himself without a recording contract in late 1968. For the next 18 months he continued the gruelling tour schedule he had maintained since returning to rock’n’roll in 1964 – pushing the flamboyant and campy style of his live shows to new heights and sliding further in the decadent showbiz lifestyle he had repudiated in 1957. Despite the toll his new life was taking on his health and spiritual commitment, show biz flash provided the path out of his creative cul-de-sac.

On 22 September 1969, Little Richard appeared on the nationally syndicated Della Reese Show. With his outrageous, over-the-top performance style and flamboyant persona, Little Richard was a natural for television and audiences loved him. What had been scandalous to adults in Middle America in the 50s, captivated a new generation of grown-ups remembering Little Richard from their youth.

In February 1970, he appeared on The Dick Cavett Show on the ABC network and offers for more talk show bookings began to pour in. With newfound attention focused on Little Richard, he approached his friend Mo Ostin, head of Warner Brothers Records about a new recording deal. Ostin quickly signed him to Warner’s Reprise imprint. Little Richard was determined to take advantage of the new opportunity. Booking time at celebrated FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, Little Richard produced the sessions himself, mixing his band members with members of the renowned FAME Rhythm Section. The result was The Rill Thing, a Southern soul-funk-country-rock masterpiece.

King of rock’n’roll

Released in August 1970, the album garnered rave reviews and the debut single, Freedom Blues, co-written by Little Richard and Esquerita, hit No.28 R&B and No.47 pop, making it his highest charting single since 1958. With high hopes, Reprise released a second single, Greenwood, Mississippi and highly promoted the album, but neither the second single nor the album managed to dent the charts. Nevertheless, the album was one of Little Richard’s proudest achievements. Subsequent generations recognised its charm with the title track of the LP, the deep groove instrumental, The Rill Thing, becoming a favourite of hip-hop artists, sampling it on countless records.

Despite the disappointing album sales, Little Richard’s profile continued rising as he became a regular on TV talk shows, often appearing with the cream of Hollywood glitterati. His increasing popularity as a TV personality also boosted his reputation as a live performer, leading to bookings at larger and better paying venues.

In May 1971, he gave it another go, recording his next album in Hollywood with soul and pop producer HB Barnum at the board.

Released in October 1971, The King Of Rock And Roll put the funk and country elements on the back burner, and moved the campier elements of Little Richard’s rock’n’roll persona to the forefront. The result was a fun, yet definitely “fluffier” record than its predecessor. Many of Little Richard’s diehard fans loved the country soul grit groove of The Rill Thing and were disappointed.

Writing in Rolling Stone, Vince Aletti said: “Much of the album seems designed around the talk show personality rather than the singer, giving it the sticky veneer of a jive extravaganza.” In terms of sales, the campy Little Richard proved even less successful than the deep soul brother, as The King Of Rock And Roll barely dented the charts at No.193 and the sole single from the album, Green Power, missed the charts entirely.

For his third Reprise album, The Second Coming, Little Richard turned to his old producer “Bumps” Blackwell. Looking for a sweet spot between retro and modern, Blackwell recruited several young rock musicians and took a more back-to-basics approach in terms of material. Released in September 1972, the album failed to please almost everyone and didn’t dent the charts. With time, the album’s critical reputation has improved but is hampered

by overproduction with Little Richard’s powerhouse performances often buried in the mix.

In May 1972, four months before the release of The Second Coming, Little Richard and Bumps Blackwell returned to the studio to cut material for a fourth Reprise album. The next album, Southern Child, was completed and ready for release when Reprise cut their losses and shelved it. The “lost” record was eventually released in 2005 as part

of the Rhino Handmade boxset, King Of Rock And Roll: The Complete Reprise Recordings.

After leaving Reprise in late 1972, Little Richard appeared in the documentary/concert film Let The Good Times Roll, delivering a scorching live set, filling one side of the film’s 2LP soundtrack album released by Bell Records. As demand for live appearances increased, he abandoned recording with one notable exception. As he explained to Charles White: “We were about to start a tour and we needed some money. So Robert “Bumps” Blackwell and me got a deal for one album with an advance of $10,000 from (Modern Records). We went into the studio and did it in one night.”

Recorded in January 1973 at FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Right Now! proved to be the purest expression

of Little Richard’s talents since The Rill Thing. Simply recorded with no commercial aspirations, Little Richard’s raw talent was on display as he runs through eight perfect examples of gritty Southern soul.

Released in early 1974 on Modern’s “United” imprint, the album went straight to the bargain bins, supplying many Little Richard fans a treasury of great music for only $2.98.

For the next three years, Little Richard continued touring while his lifestyle swirled out of control. In 1976 he recorded yet another set of “Greatest Hits” remakes for the TV marketed-record label K-Tel and left rock’n’roll for the second time. As he recalled in a 1985 interview for the British television network Channel 4 programme The Tube: “I gave up rock and roll in 1976. I had a lot of death in my family, my brother fell dead, he had a heart attack, he was 32 years old. I had another friend who got shot in the head, another friend of mine got cut up with a butcher knife, another friend of mine had a heart attack, then my mother died. Then my nephew shot himself in the head,

and so I decided I would just give my life to being an evangelist.”

Little Richard eventually returned to rock’n’roll in the mid-80s, at last finding a balance between serving the Lord and the temptations of rock’n’roll. Although they are often overlooked and unjustly disparaged, Little Richard’s 1964 to 1976 recordings are a fascinating treasure trove for fans of rock’n’roll at its finest.