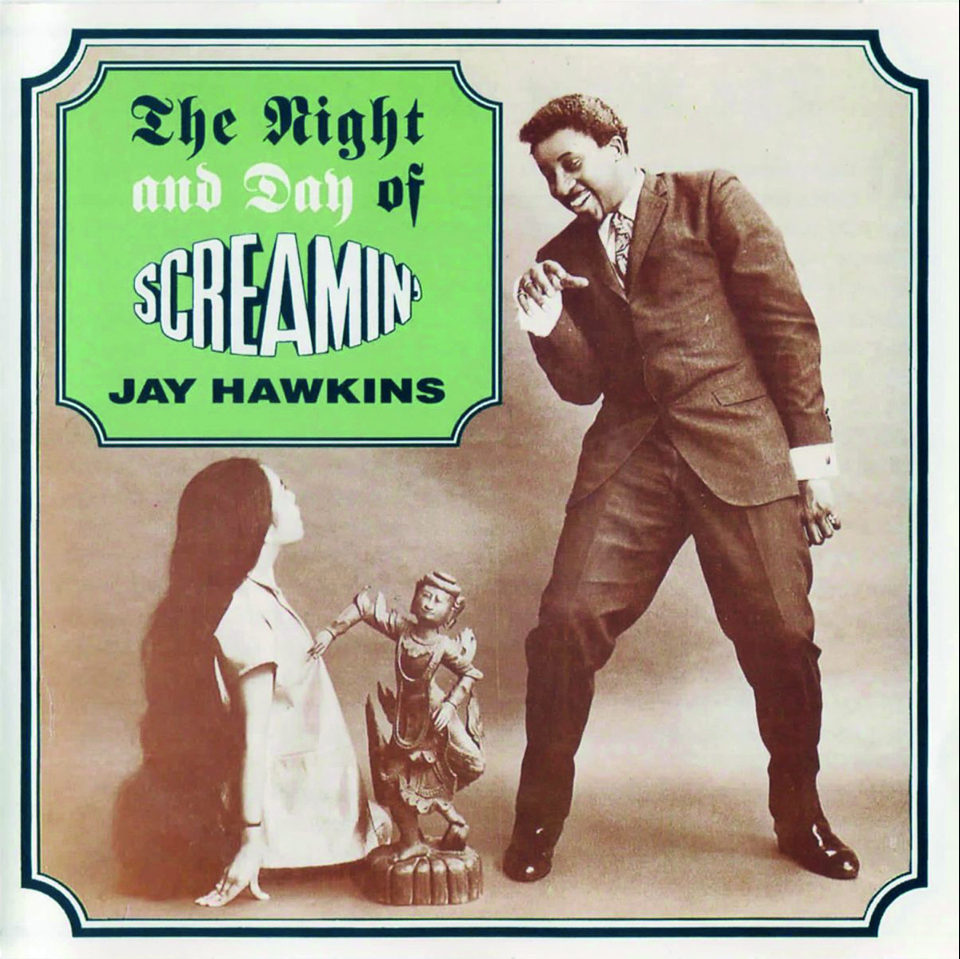

For years after its release in 1966, The Night And Day Of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, recorded in Britain, was an undervalued and almost forgotten album until its CD reappearance in 2017. In fact, it showcases an artist who was far more versatile than his familiar image suggests… By Jack Watkins

It’s fair to say that during his lifetime, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’ reputation as a recording artist was outshone by his standing as a charismatic live performer. His biggest song, the controversial, censored I Put A Spell On You, sold well enough but mysteriously never figured on any charts after its release in 1956. Only his monotonous recital of Tom Waits’ long-winded Heart Attack And Vine gave Hawkins a minor late-career near hit, when it crawled to No.42 on the UK chart in 1993. Across the years he committed many extraordinary performances to wax, but there was a frustrating lack of consistency.

LPs appeared sporadically and varied in quality. There’s a case for arguing that the American’s debut album At Home With Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, released on Okeh/Epic in 1958, is an underrated gem (see boxout). But although he sang on some of the tracks on the poorly recorded A Nite At Forbidden City album, made at a downtown Honolulu club of that name around 1963, his second solo LP didn’t emerge until 1966.

The Night And Day Of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins was recorded at London’s EMI Studios in St John’s Wood, soon to be known the world over as Abbey Road. Prestigious as it might have seemed for Hawkins to be working in the space utilised by The Beatles and other top EMI stars like Cliff Richard And The Shadows, Gerry And The Pacemakers and The Hollies, it came during a serious career lull when he was struggling to get back on track.

Although I Put A Spell On You, paired with Little Demon as a Fontana label 78 in the UK in 1958, and an eponymously titled 10″ album released in France the same year, had been the only officially available material on this side of the Atlantic into the early 60s, these records and clips of him performing the song on television had been enough to intrigue a generation of young British fans.

Photographer Brian Smith was a habitué of the Twisted Wheel Club in Manchester, where the influential DJ Roger Eagle had been running a “Where’s Screamin’ Jay?” campaign in his R&B Scene magazine, since so little had been heard about him. “We were going round asking everyone we knew, ‘Where’s Jay?’” recalls Brian. “So when Little Richard toured Britain in 1964, I asked Don ‘Sugar Cane’ Harris, of Don & Dewey, who backed him on some of the shows. He said he was a great friend of Jay’s and that he’d just seen him at the Forbidden City in Honolulu, where he was playing piano and acting as MC.”

A delighted Smith wrote an admiring letter to Hawkins, followed by missives from other Twisted Wheel Club devotees. Hawkins, as charming as he was eccentric, quickly replied with friendly and detailed letters, clearly “knocked out”, in Brian’s words, that people in England knew his work. Around the same time, two jazz buffs from New York, John and Gloria Cann, had caught Hawkins’ act.

Moved by the spectacle of this immense talent reduced to performing in a Hawaiian tourist joint, they wrangled him a modest deal with Roulette Records in New York, for whom he cut an unissued version of Buddy Knox’s Party Doll, together with a searing new recording of The Whammy, which he’d first tackled in 1955, and which was coupled with Strange on a single.

The Whammy, along with I Hear Voices, recorded a couple of years earlier and reissued around the same time, were hugely eccentric tracks and proof that Hawkins still had it. Although the single died in the States, the intact Hawkins roar and the enthusiasm of young British fans was enough to persuade UK promoter Don Arden to organise a first British tour in early 1965, at the end of which The Night And Day… was recorded.

It was probably Arden’s standing as a leading UK promoter that secured Hawkins his EMI studio session slot. Most of the album was recorded in a single day, the singer having rehearsed the majority of the numbers at the Twisted Wheel with the Blues Set, a British ensemble who had provided reliable backing across the tour. According to Brian Smith, the band, of which Clive Powell was once a member in his pre-Georgie Fame days, were all set to play on the album until Arden “blew them out at the last minute” and told them he’d decided to use session players instead.

The identities of these sessions players remains a mystery, though it’s been speculated that they included Soho jazz

club luminary Ronnie Scott on sax and electric guitarist Joe Moretti, remembered for his blazing studio work with Nero And The Gladiators (In The Hall Of The Mountain King), Vince Taylor And The Playboys (Brand New Cadillac) and Johnny Kidd And The Pirates (Shakin’ All Over).

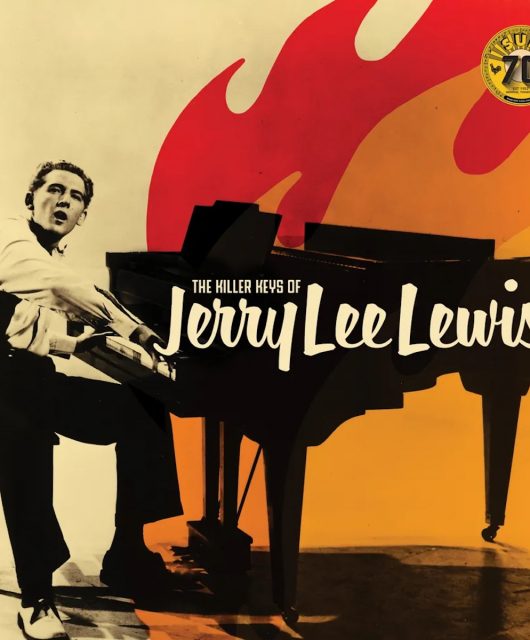

Helming the production was the great Norman Smith, sound engineer for numerous Beatles recordings and soon to work with Pink Floyd and The Pretty Things. Smith would later achieve pop success in his own right in the early 70s with uniquely styled recordings under the moniker Hurricane Smith, notably Don’t Let It Die and Oh, Babe, What Would You Say? However, while Norman was an experimental studio sound maestro, on the Hawkins LP he kept it simple.

The album begins with the Cole Porter standard Night And Day, set to a relatively restrained bossa nova groove, before kicking into a more swinging beat. Hawkins delivers a typically tonsil-stretching climax, exaggeratedly holding onto his final note, while the organ plays through the fade out. The ballad In My Dream has some twiddly blues guitar soloing, but is given a straight vocal rendition by Hawkins, demonstrating a baritone with a range so much wider than almost any of his rockin’ contemporaries.

I Wanna Know and Your Kind Of Love are routine R&B swingers, typical of the mid-60s R&B boom as, of course, is the Hammond organ. Change Your Ways has a smokier, more laid-back blues feel, though Hawkins stills does some hollering. Side One closes with a foray into traditional Hawkins territory with the lively Serving Time, which borrows the riff from Clyde McPhatter And The Drifters’ 1953 single Money Honey. It’s one of the first side’s most effective numbers, and the album’s briefest.

On the flipside, Alright, O.K. You Win has a ska rhythm known at the time as bluebeat, where Hawkins builds the tension nicely before letting loose with some vintage screeching and shouting. Next came a classic. Across his career, Hawkins would sometimes alight on a song that really moved him and sing it with a passion few artists could match. Please Forgive Me is one such example. He’d recorded it in his Okeh days, but for this new version he ditches the spoken-word approach and sings it with a feeling that touches on greatness.

The plaintive trumpet above the triplet rhythm is perfection. Move Me has a keyboard groove reminiscent of Booker T & The MGs’ Green Onions, while I’m So Glad rides on the type of breezy sax and trumpet riff that Hawkins loved so much. My Marion is another of the LP’s standouts, a triplet-driven ballad, with a superb vocal and a doo-wop feel. The choppy notes on the organ are highly effective and there’s a depth to the overall sound. All Night, however, is a routine closer which Hawkins would return to, this time with a girly chorus, for a later recording session when back in the US.

In the event, after a bust-up with Don Arden caused a hasty curtailment of the 1965 tour, the album did not appear until the following year, released on Shel Talmy’s fledgeling, short-lived Planet label. With little promotion, sales were poor.

However, a long-lasting link with Britain had been forged. Along with Brian Smith, whose carefully framed photos have featured in nearly every Hawkins retrospective ever since, a young Bill Millar was among the bevy of rock and R&B enthusiasts who were there to greet and befriend Hawkins when he first flew into London Airport in 1965. Millar, a formidable and eloquent writer, would become one of his great champions, ensuring that his legacy was remembered.

Hawkins was an intelligent and funny – if highly unreliable – man. He fascinated his British friends not just by his stage persona, but by his personality and utterances off it. He was a rock’n’roll pioneer, but his voice was capable of more, and he knew it. When The Rolling Stones asked him to open their New York show in 1981, they stipulated that he perform with his famous coffin and ragbag of ghoulish props. To his annoyance, there was no escaping the melodramatics of I Put A Spell On You.

“If it were up to me I wouldn’t be Screamin’ Jay Hawkins,” he’d told Nick Tosches in a 1973 interview. “I mean, I’ve got a voice. Why can’t people just take me as a regular singer without makin’ a bogeyman out of me… I come along and get a little weird, and all of a sudden I’m a monster or something. People won’t listen to me as a singer.”

In reality, the obsession with the manic side of Hawkins was entirely of his own making, not a media-foisted image. And it was nothing to be ashamed of, even if the antics sometimes wore thin.

But if he’s looking down from the heavens today, Hawkins is probably still mighty proud of the Planet album. While

it’s not flat-out ‘Crazy Jay’, it’s a decent halfway house, a night and day picture of a man who was both an exceedingly fine singer and a flamboyant extrovert who loved playing to the crowd.