Shakin’ Stevens took rockabilly-lite to the top of the pop charts in the early 80s, but his first album with The Sunsets is one of the most explosive UK rock’n’roll albums ever. Jack Watkins revisits a lost and rare classic with the help of those who were there…

Shakin’ Stevens’ 80s hit-making juggernaut left no space for reflection on the earliest part of his career when he was cutting earthier, rootsier rock’n’roll. It meant the memory of his work with The Sunsets and their almost heroic part in keeping the British rock’n’roll flame alive fell off the radar.

Yet, given a fairer wind, their debut album A Legend could have sparked a full-scale rock’n’roll revival several years ahead of the event. When the album came out in 1970, some might have tagged it a retro blast from the past. But as far as these tough rockers from South Wales were concerned, “proper” rock’n’roll had never died. To them, this was no nostalgia trip, which is probably why the album holds up well today.

Many current artists tackling classic rock’n’roll are too reverential, the strain to reproduce the correct sound leading to a tepid pastiche. The Sunsets were authentic enough, though they often used an electric bass, but the key to A Legend is the way they just attacked the music, confident in their familiarity with songs which had been part of their live sets for years.

The other thing about A Legend is that, though The Sunsets were Shaky’s band, they’re not like faded wallpaper in the background. When Shaky went solo, the spotlight was always on him: at this earlier stage, the older guys playing behind him were just as crucial to the sound, none more so than drummer and occasional vocalist Rockin’ Louie. In fact, for all the later comparisons with Elvis, Shaky’s first idol was Louie himself who, from the early 60s, had been frontman of The Backbeats, a rock’n’roll outfit from Penarth with a big following in the Cardiff area.

Rockin’ Louie and his band, along with manager Paul “Legs” Barrett, were first generation rockers, genuine lifestylers of the scene since the first time US rock’n’roll broke on British shores, whereas Michael Barratt, to give Shaky his real name, gained access to the music via his elder siblings’ record collection. While his contemporaries were switching on to the mid-60s beat music, he was hooked by 50s rock. According to Legs (no relation of Michael) he was “a young kid in awe of Rockin’ Louie and The Backbeats,” a local boy who often got up to sing with them, and they even dubbed him Rockin’ Louie II. But not for long…

A Legend In The Making

As the 60s rolled on, even The Backbeats couldn’t get enough gigs playing rock’n’roll and folded. Yet Michael Barratt persisted, forming a series of bands and a stage style promising enough to bring him to the attention of Legs, by now running a Penarth record shop. Paul “Legs” Barrett became his manager while gradually bringing in ex-Backbeats personnel like Rockin’ Louie, on drums, and Carl Petersen on lead guitar.

By the time of A Legend, Steve Percy had come in on bass, and Paul Dolan played tenor sax. Londoner Trevor Hawkins was on piano. The inspired name Shakin’ Stevens And The Sunsets? It was picked up from an eccentric roadsweeper working the streets near Shaky’s home, holding his broom like a guitar while proclaiming that his rock’n’roll band was called Shakin’ Stevens And The Sunsets.

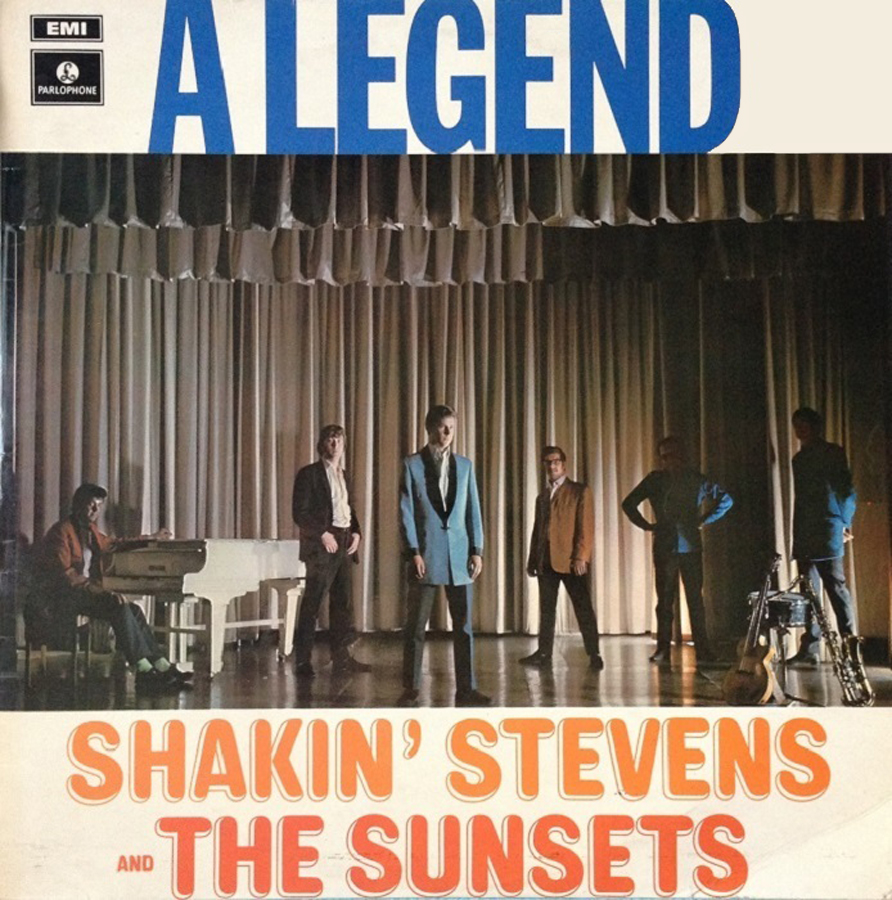

The band’s profile quickly grew. Supporting The Rolling Stones, at the Saville Theatre in London in 1969, there were gasps when the curtains went up to reveal, as one hack put it: “a rock group looking as if they had stepped straight out of the local Palais circa 1958.”

In drapes and crepes, they were curiosities. Radio 1 DJ John Peel came to a show and offered them a deal on his own Dandelion label. But although they cut an album worth of demos for Peel, they suspected his enthusiasm for roots rock was skin deep. “We didn’t like the idea of being a novelty thing,” recalls Rockin’ Louie. “It made us look quaint, which was not how we saw ourselves.”

In the event, they were rescued by the arrival of Dave Edmunds. Another product of Cardiff, Edmunds invited them to record an album at his Rockfield studio in South Wales. A true disciple of early rock, even if his own excursions into it were highly individualistic, he had known The Backbeats. He was a better fit for The Sunsets than Peel, and the added inducement of going with him was that he could get them signed to the prestigious EMI label, Parlophone.

According to Rockin’ Louie the songs they’d put down for Peel formed the basis of the A Legend album, though Edmunds initially seemed to believe he was going to be recording Rockin’ Louie and The Backbeats. “Dave Edmunds didn’t really want Shaky then, he wanted Louie,” remembers Legs.

“I said: ‘No, Louie’s my pal, but it’s Shaky’s band’. So he had to take him as part of the package deal… and Shaky was crying about it in the studio.” In the event, Louie would sing three songs, and duet with Shaky on another, the album benefiting greatly in terms of texture and variety, galling as that may have been for the young Shaky.

The album starts fast and stays that way almost all the way through. It’s a textbook of how to play classic rock’n’roll, the songs being short with no filler, and no overplaying by self- indulgent instrumentalists. Some of the tracks chosen have subsequently become 50s-era crown jewels. But, in 1970, these songs were just fading from view. As Rockin’ Louie says: “We thought we were keeping them alive, really.”

So the band just plunged in, laying down compelling new versions, floating on a tidal wave of energy, enthusiasm and love.

The LP kicked off with Cast Iron Arm which Roy Orbison And The Teen Kings guitarist Peanuts Wilson had recorded in 1957. The Sunsets kept close to the original, but the production effect was muffled, sax, guitars and drums merging to form a captivatingly rhythmic wall of sound. A similarly fuzzy effect was achieved on Jack Scott’s classic Leroy. Scott and his backing vocal group The Chantones were in a league of their own, but Shaky And The Sunsets just motored through to make their own stonewall classic rendition, Edmunds unstinting in his use of echo.

On Flying Saucers, once again they were up against it. There may never have been a more thrilling intro to a 50s rocker than the siren-like guitar of Roland Janes and crashing symbol of JM Van Eaton which announces Billy Riley’s Sun original. The Welsh boys didn’t let that bother them and just picked up from where they’d left off with Leroy, like a band building up audience frenzy at a gig.

Please Mr Mayor, an old Roy Clark song, had a cascading, rumba-style rhythm which suited The Sunsets well. Carl Petersen stuck pretty well note for note to Clark’s stinging guitar solo, but Paul Dolan’s sax set an infectious rhythmic counter pulse. If Shaky sometimes sounded a bit underpowered on these tracks, sharing alternate verses with Rockin’ Louie on Lights Out induced him to step up a gear.

This track also had Trevor Hawkins tearing into a barrelhouse piano solo. I’ll Try, a Conway Twitty ballad, finally gave everyone a moment to catch their breath. The vocal was a foretaste of the future Shaky, the pop idol of millions of schoolgirl posters, with that memorable voice, supple and frail at the same time.

Rockin’ Louie took over singing duties on Smiley Lewis’ Down Yonder We Go Balling, showcasing his love for New Orleans rock’n’roll stylings. Louie’s warm tones, more laid back than Shaky’s, were perfect for the material, and this is one of the standout tracks on the album, the sound of sheer happiness. Hawkins was again memorable on piano, delightfully teaming with Dolan’s sax, for a loose, off the cuff feel. Dave Edmunds strummed the banjo in homage to Smiley Lewis.

Then Hawkins who, with his long sideburns, bootlace ties and drapes, looked every inch the teddy boy, closed off the first side with his own composition, the pounding piano boogie Hawkins Mood, summoning the ghosts of keyboard maestros of old. It brought to an end what may have been just about the most thrilling top side of a rock’n’roll album ever cut in Britain.

Down On The Farm kicked off the second side, keeping up the standard, once again Rockin’ Louie on vocals for this Big Al Downing song. Legs had picked on the number after the legendary Ted, “Breathless” Dan Coffey, following one of his famous forays to the US in search of collectibles, had played him the demo Downing had done for Sam Phillips.

The Sunsets’ recording is notable for the snare drum sound, achieved by Edmunds placing a microphone under the snare instead of, or in addition to, the one normally placed above the drum set. With a gated reverb, it created a rattling percussive effect that would be a signature sound of The Stray Cats and The Polecats albums Edmunds produced 10 years later. Additionally, the track pioneered the powerful string bass sound heard on those albums. Legs reveals Edmunds achieved it on this track by playing the bass with a drumstick.

Not all of Side 2 of A Legend matched the wall-to-wall brilliance of the first side, but versions of two train songs rendered immortal by Johnny Burnette And The Rock ’n Roll Trio succeeded by turning them into churning, boogified monsters, Shaky singing authoritatively without trying to replicate Johnny Burnette’s maniacal screeches.

Lonesome Train pushed Hawkins piano to the front, but the real killer was The Train Kept A Rollin’. How could anything compare to Johnny Burnette And The Rock ’n Roll Trio’s version? Yet Shaky and The Sunsets somehow laid down a shimmering, hoppin’ and a boppin’ rock’n’roll wall of sound that stood proudly on its own terms.

Rockin Louie was on vocals for I Hear You Knocking, another song by his beloved Smiley Lewis. The good time feel was signed off by closing with a couple of Chuck Berry songs, Thirty Days, and a shortened School Days, for a whooping end-of-term-party effect.

The Sunsets Fade

Unfortunately, neither the album, nor a single, Spirit Of Woodstock, along with I Believe What You Say, one of the album’s weaker tracks, sold well. Both Edmunds and the band had wanted Down On The Farm on the top side. And with Edmunds falling out with EMI after he released his own version of I Hear You Knocking on a different label after they’d rejected it, the band were caught in the fallout and got dropped.

The band cut more quality material in the seven following years until Shaky’s abrupt departure in 1977 – they even did a fine version of Jungle Rock before Hank Mizell’s original was re-released with massive success in 1976 – but they never scored a hit. A rancourous court case over unpaid royalties after the re-release of A Legend on the back of Shaky’s success, pitted Stevens and Edmunds against The Sunsets in the 90s. It’s one of the saddest things to relate that the rift has never been healed.

So Shakin’ Stevens And The Sunsets were an unlucky band, but often a great one, admired by many beyond the rock’n’roll confraternity, including Sex Pistol Johnny Rotten and Dr Feelgood’s Wilko Johnson. The seemingly presumptuous title of A Legend was actually taken from a favourite 50s sci-fi book belonging to Legs, I Am Legend by Richard Matheson, the idea being to tribute rock’s legendary pioneers.

But there is something legendary itself about the exploits of this band, from a time when most musos thought the sort of music they played was beneath their consideration. There’s a timelessness about The Sunsets’ sound that has outlasted that of many trendier, more long-winded bands of the same period. They deserve a much bigger place in any history of British rock’n’roll than they have so far been accredited.