Of all the “woulda, coulda, shoulda” rock’n’roll stories, none would have, could have, and should have hit the big time more than Billy Lee Riley… By Rocko Jerome

Sam Phillips: “Ever since the day I set foot in Memphis, which was in 1939, I’ve always been a person of philosophy. Some of it’s pretty corny, some of it’s not all that good, and I don’t know that you’d want to stake your life on some of my philosophy, but I mean I have lived by philosophy. And I sure do like for people to correct me.”

Billy Lee Riley: “And I know that for sure, because you philosophised to me a lot of times.”

Sam: “Billy had a bad case… or a good case… of feeling like he was overlooked.”

Billy: “And I was.”

(From the documentary Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy Of Sun Records.)

Where Elvis was destined for the matinée, Carl Perkins embodied the very essence of rockabilly, and Jerry Lee Lewis was a volatile mix of unfathomable talent and caustic self-destruction, Billy Lee Riley mastered the dark menace of the blues, with his raspy rhythm and blues vibe and a delivery that left little doubt that he was a man not to be messed with. None felt more adult and competent.

He was born in Pocahontas, Arkansas, in 1933 and, like many people from that region, a bit of Native American blood coursed through his veins. He grew up hard through the Great Depression, his father taking jobs wherever he could, including time as a painter and sharecropper. Billy Lee heard country on the radio and blues in the fields. It penetrated his mind, and he grew up with dreams of making money by making music.

He would win a talent show at age 14, but soon after standing behind a mic for the first time, he would learn to shoot a firearm as a 15-year-old soldier. His sister would cheat and bear witness on the age of consent forms, declaring Private Riley a fair and square 18-year-old. The army was a way out of crippling poverty and he was thrilled at the general issue three square meals and a cot. He would spend the next few years meeting other enlisted musicians and playing in bands, learning the harmonica and how to work a crowd for all they were worth.

Once discharged, he got a gig truck driving in 1955. It was clear he was destined for just about anything else after he wrecked twice. Music seemed to be an obvious choice. He set about writing tunes and looking for a way in. Right from the start of his career he was a force to be reckoned with. Trouble Bound was the tune that brought him to the proverbial party, the mid-tempo ballad of a man about to do something terrible when he comes upon his woman and another man drinking and living it up at a crowded bar. It thuds along like a thunder rumble in the distance, the calm before the storm that could prove deadly. This was no Peggy Sue saccharine puppy love:

Well, the barroom, it was crowded,

Everybody there was high,

That’s when I seen my baby,

While I was passing by,

And I couldn’t understand it,

Didn’t think she’d let me down,

She was with another,

And I was Trouble Bound.

Billy Lee sang the words he wrote like he was relating them to his arresting officer just hours after turning the head of the man who cuckolded him into a canoe. The tune was cut as the first outing for producer Jack Clement’s Fernwood Records. When it attracted Sam Phillips’ attention, the man behind Sun Records bought the rights to

the song, the label, and hired both of the men outright.

It was 1956. The future looked bright for Billy Lee Riley. For a handsome man with chiselled features possessed of a captivating voice and natural charisma, getting signed to the label that had introduced the world to Elvis Presley felt like a major coup. Stardom had to be a mere heartbeat away. In early ’57, Phillips would set his new find before the cream of the crop of his session men. Along with Roland James, the guitarist whom Billy Lee brought along, the band would be rounded out with Marvin Pepper on bass, Jimmy Van Eaton on drums, and one Jerry Lee Lewis on piano.

They would function as the well-oiled rifle, firing frontman Billy Lee Riley like a blazing hot bullet. A cash-in on a current sci-fi fad, Flyin’ Saucers Rock’n’Roll would be a mere cornball novelty in lesser hands, but it was played and sung with such raw power that it never fails to raise goosebumps, even (or maybe even especially) when the record is spun today. The song gave the band their name: Billy Lee Riley And The Little Green Men.

Crowds went wild and literally ripped the green felt suits off the band and their leader, but the single sold poorly. Still, all involved (short of Jerry Lee Lewis, whose plate was quickly becoming full) were intent on trying again.

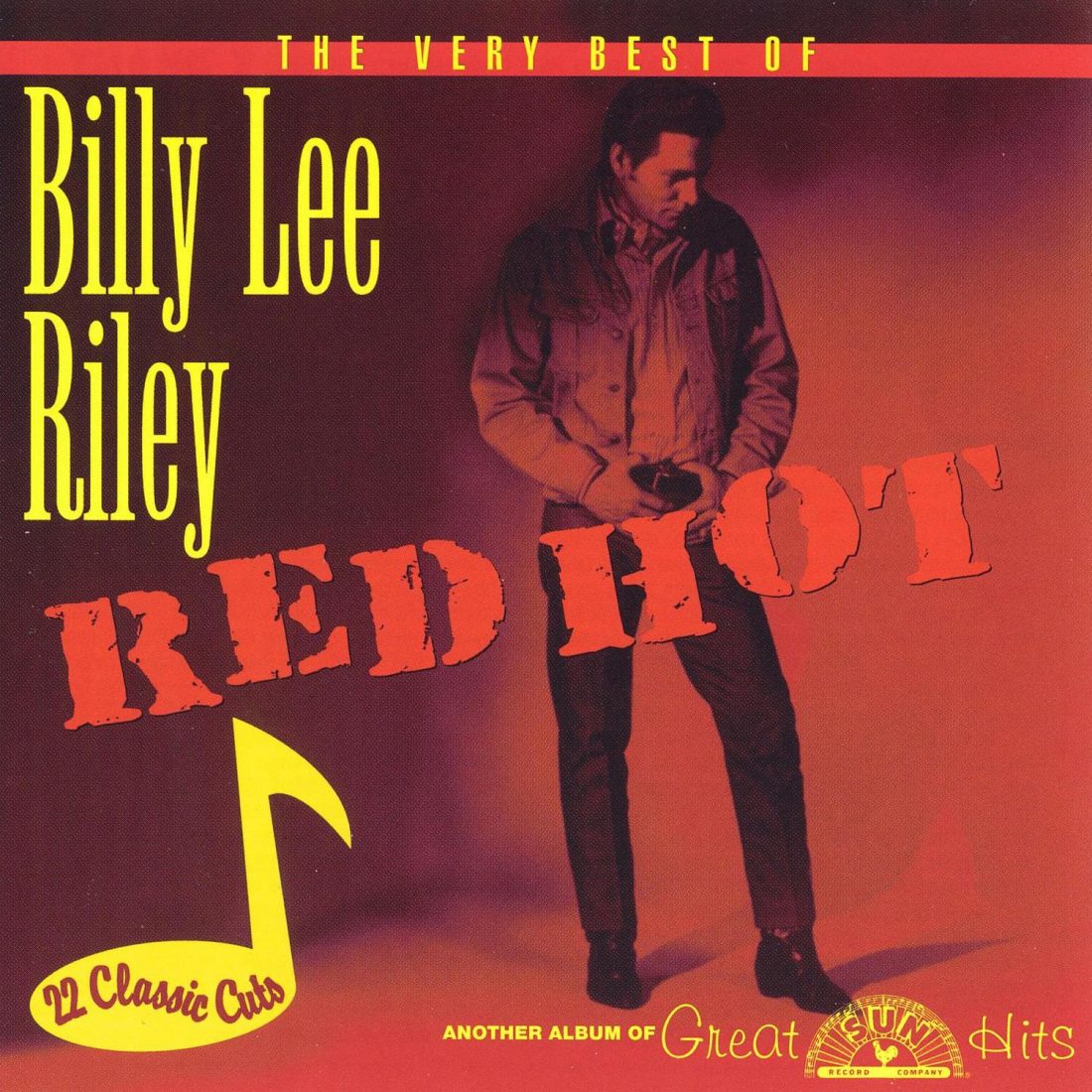

Next time around, they crafted a masterpiece that would stand the test of time, and become an anthem for rockers in decades to come: a take on Billy “The Kid” Emerson’s Red Hot. A raucous number with a singalong chorus that was at least as good as any other number the likes of Alan Freed would be blasting, Red Hot had success written all over it…

But the record stalled when the promotional juice wasn’t behind it.

Phillips, for his part, felt that putting all his label’s support behind Jerry Lee Lewis was nothing less than doing God’s work. “You can save souls!” he had pleaded with the piano-slamming dynamo during a drunken recording session. “How can the Devil save souls?” Lewis shot back. That defiance would only make the Louisiana wildman grow fonder in the heart and ambitions of Phillips. Undeterred, the Sun promotion machine would shine on Jerry Lee Lewis almost exclusively in 1957.

Billy Lee wondered why his career went nowhere, until one day he ear-hustled Phillips on the phone in his office. The Sun King was cancelling DJ orders for Red Hot from states away, and telling them to pick up spins on Jerry Lee Lewis instead. That sales-driving airplay around the country was critical. If kids didn’t hear the record, they weren’t too likely to buy the record, and in the 50s rock’n’roll age, competition was steep.

Billy Lee had a regional hit thanks to local airplay, but as noted by Memphis musician and producer Jim Dickinson in Robert Gordon’s It Came From Memphis: “It was years before I figured out that this stuff I heard on Dewey Phillips’ show wasn’t popular music. I certainly didn’t realise that he was playing things that nobody else played. Like Red Hot by Billy Lee Riley, I didn’t realise that wasn’t a hit until I moved to Texas for college.”

Then Riley saw red. He had been delivering the goods and waiting patiently while, all along, the man he trusted was slitting his throat. His anger swerved into violence as he got lit and began destroying the studio until Mr. Phillips stepped in. The two men would talk till dawn.

No one knows for sure what was said between the two of them that night, but one thing is clear: the legendarily silver

tongue of Sam Phillips would work its magic on Billy Lee Riley. He would remain a Sun Records artist for at least one more go. Billy Lee’s Wouldn’t You Know was released the same time as Jerry Lee’s Breathless. Once again, the fair-haired boy had the favour.

Billy Lee went to Nashville and the Brunswick label and cut a single that went nowhere; he was courted by Steve Sholes and Dick Clark, but didn’t bother to show up to the sessions. He even started his own label, Rita, which also failed to bring him his own hits, although he produced Mountain Of Love for Harold Dorman, a minor hit in 1959. Perhaps wary of northern major label A&R men, perhaps out of a sense of loyalty, the Red Hot Rocker would return to Sun like a moth to flame.

The years rolled by and, after its brief reign, rockabilly was no longer the thing in the public eye. Billy Lee would cut soulful shakedowns like San Francisco Lady and Workin’ On The River that were as good as anything, but no one seemed to notice. If Billy Lee ever believed that the world he lived in was a meritocracy, he sure didn’t by the mid-60s.

Somewhere along the way, Billy Lee Riley seemed to start making music for himself more than for any shot at fame. Tallahassee, a tune sung from the point of view of a father struggling to save the life of his sick son by moving the family to a warm climate only to have him die there and the family bankrupted, didn’t exactly have “hit” written on it. The same was true of Potter’s Field, a song about the kind of graveyard where no one goes to mourn. The words – “He once had a mother who loved him and sang him a lullaby” and “No one knows another man’s woes or the depths

of his despair” – gave some indication of the state of mind Billy Lee had with him at that time.

A very mature Billy Lee recorded a new tune called Kay for the newly dubbed Sun International label in 1969,

a slow burn song sung from the point of view of a man whose woman has hit the big time as a singing star and left him holding the bag, working as a cab driver just to get by. In a Creedence Clearwater Revival groove, Kay was called “The best record Riley ever recorded” by Sam Phillips. It truly is a fantastic piece of work, and the fact that it’s even more obscure than anything else he released tells the story of the mishandled career of this artist.

Years turned to decades. As rockabilly was revived as a pop culture cult and the ascendency of the internet transpired to create a network for kindred soul fans to communicate, festivals sprang up around the planet. Those who had drunk from the cup of fame, like Jerry Lee Lewis, often considered themselves too big to appear on a bill with the likes of latter-day rockabilly acts like High Noon or Big Sandy And The Fly-Rite Boys, and would have likely phoned a performance in if they did.

On the other hand, after having worked in construction and other odd jobs to keep the lights on, Billy Lee was up for anything. He answered the call, and when he walked out in front of a crowd, any crowd at all, he could always be depended on to deliver the goods. When that man performed, he always gave it his all, intent on making that audience wonder as much as he had why Billy Lee Riley had not been a household name from 1957 to the present.

The subject would often turn, both in on-stage banter and off-stage conversation, to the role the flakiness of Sam Phillips had played in Billy Lee’s life. He would joke about it, but it was clear that the bitterness was there inside him and burned hot. He would usually perform songs like Shake, Rattle And Roll and other hits made famous by others from the 50s.

When devoted fans asked him to consider playing some more of his own tunes, he would say, “I appreciate it, but nobody but you wants to hear that!”

Finally the day came when the available, surviving Sun luminaries and their erstwhile leader were brought together for a 2001 documentary, Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy Of Sun Records. Live on tape, Billy Lee finally got to give his old adversary a piece of his mind. Perhaps surprising even himself, in one breath he told him “you screwed me” and “…but I don’t hate you.”

Phillips took the medicine well and rolled with the punch. For his part, years previously he had said, “Riley was just a damn good rocker, but man, he was so weird in many ways. He interested the hell out of me, but he was not the easiest person to deal with. When he took a drink he’d become almost a different person. He just never achieved his potential in my studio. I’m sorry I didn’t do more with him. I was disappointed we never broke him into the big time.”

Billy Lee made a point to alert his fans and friends to watch the programme as it aired on public television. He was noticeably different after that. In his last handful of years, he seemed content with the legacy he had built among the faithful rock’n’roll enthusiasts around the world. Always happy to sign an autograph, shake a hand, tell a story, and most especially, climb on a stage and tear a house down.

Billy Lee Riley died on 2 August 2009. Sam Phillips preceded him in death on 30 July 2003. Billy Lee mourned the loss as that of a friend.

Fortunately, his later years on this earth were marked by a peace of mind that he had perhaps been searching for throughout his life.