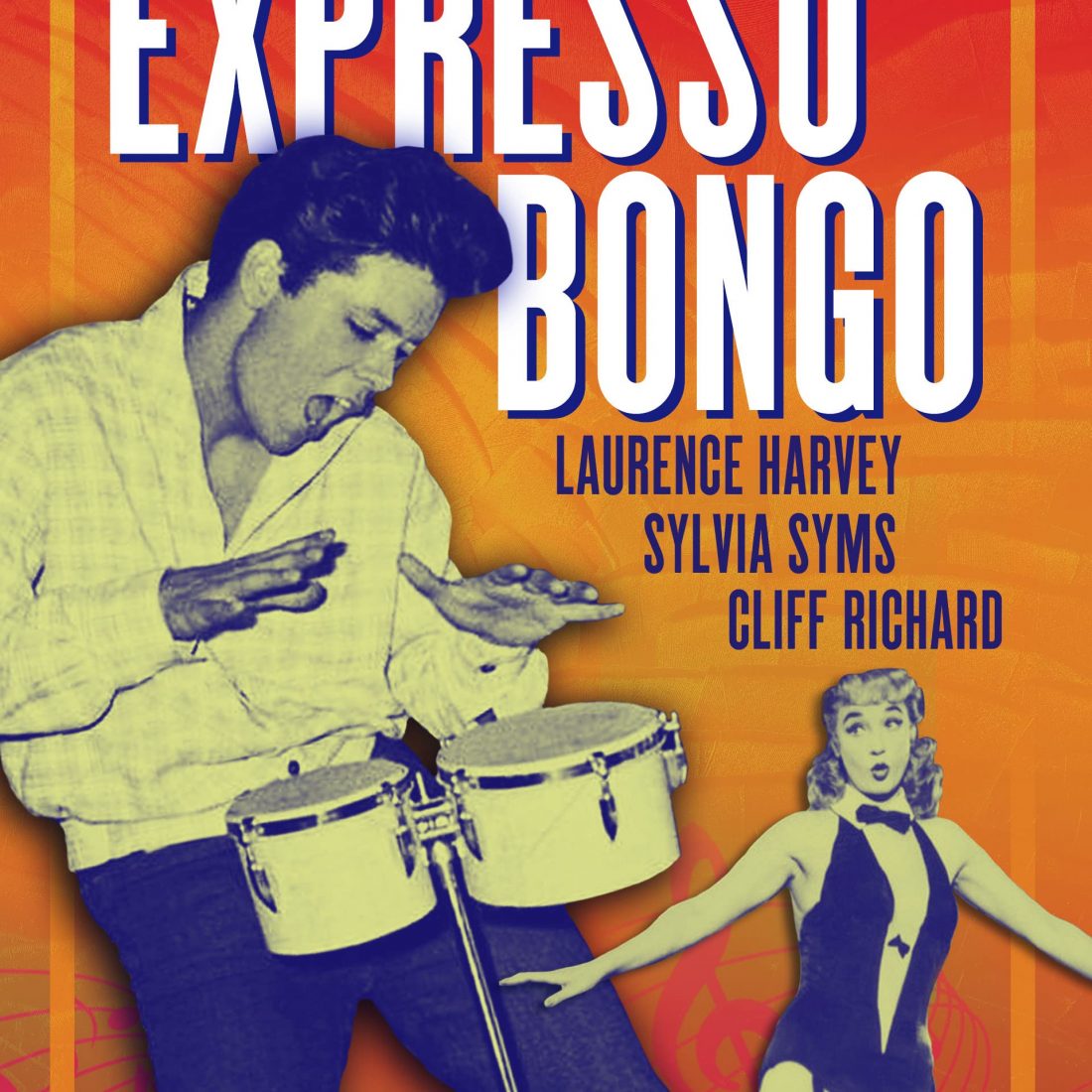

In 1959, Cliff Richard starred in a movie that would soon be considered a British classic, a gritty and cynical satire of the pop music business titled Expresso Bongo…

The tropes of the 50s British teen movie are so embedded in popular culture that when Harry Enfield sent them up in his 1989 comedy Norbert Smith: A Life, they felt instantly familiar. Of course it was always easy to mock these knocked-off exploitation flicks, with their patently over-age teenage leads and clunky kidspeak (“What ya talkin’ about, Daddy-o?”). But Expresso Bongo remains a cut above.

Admittedly, there’s little original about its story – a struggling music agent discovers a young, good looking singer and vows to make him a star – but Val Guest’s film not only fizzes with period flavour but boasts arguably Cliff Richard’s finest big-screen performance, as the bequiffed bongo player Bert Rudge (later remonikered Bongo Herbert).

That Expresso Bongo was based on a successful play, by the writer Wolf Mankowitz, automatically elevated it above more throwaway rock’n’roll fare. Mankowitz had a knack for penning whip-smart dialogue and his play was widely seen as a piercing satire of the showbusiness scene, not something that coldly exploited it. It had premiered at London’s Saville Theatre on 23 April 1958 and headlined a young Paul Scofield as showbiz agent Johnny Jackson, winning, despite its relatively short West End run, rapturous reviews, with Variety voting it Best British Musical of ’58.

Such was the fuss over Expresso Bongo that, in 1959, British Lion bid for the rights to turn it into a movie, inking Val Guest, who’d helped shepherd Quatermass to the big screen, as director. As well as being a reliable hand behind the camera, Guest was also a skilled writer, having penned many of Will Hay’s most popular comedies, and, working alongside Mankowitz, was instrumental in giving Expresso Bongo a full-blooded cinematic makeover.

Guest had considered keeping Schofield for the movie, but eventually opted for the 31-year-old Laurence Harvey. 1959 would prove to be a breakout year for the Lithuanian-born, South Africa-raised actor, who bagged another critically acclaimed role, that of ambitious young accountant Joe Lampton, in kitchen sink masterpiece Room At The Top.

Harvey would prove adroit casting as the maverick Jackson. The actor would often talk of being considered a ‘cocky intruder’ by the British theatrical establishment. Though he’d lost his South African accent during his years at RADA, he was forever reminded that he was an immigrant, and it’s that sense of not quite belonging that he brings to the part. The character of Johnny Jackson had been modelled – clearly, for anyone in the know – on pop svengali Larry Parnes, even down to the gaudy pseudonym Jackson bestows upon his teenage protege.

However, the broad Jewish accent that Harvey adopts in the film was based more on its co-writer Wolf Mankowitz than the similarly Jewish Parnes. Guest had arranged a series of lunches between Harvey and Mankowitz, so the actor could study the writer’s voice.

“I think I have it,” Harvey told Guest after the second meet-up, instructing the director to warn him if his accent wandered during the shoot. One day it did, and Harvey was forced to phone Mankowitz, just to get himself back on track. After a few minutes, he hung up and told Guest, “Okay, better roll before I forget it!”

“I don’t think [Wolf] ever realised,” reflected Val Guest in his 2001 autobiography So You Want To Be In Pictures, “that when Laurence Harvey won critical kudos for his performance as Johnny Jackson, he won them partly for sounding like Wolf Mankowitz.”

One significant difference between the stage version of Expresso Bongo and the film was that, in the play, Bongo Herbert is depicted as having few singing skills (Mankowitz was intent on painting the showbiz game as being deplorably superficial, valuing cheekbones over talent).

For the movie, Guest wanted someone plausible and authentic as the teenager who’s plucked from coffee-shop obscurity to become a rock’n’roll pin-up. He considered using one of the names from Parnes’ own stable, including Tommy Steele (“he didn’t have the vulnerability”) and Marty Wilde (“too tall to command the necessary sympathy”).

Then a call came from the 2i’s coffee bar. Guest was told about a singer who might just be the perfect fit for Bert. The director journeyed down to 59 Old Compton Street and watched a teenager named Cliff Richard and his backing band The Drifters mesmerise the espresso-supping throng. Guest offered Cliff the part on the spot, and arranged for him to sign the £2,000 contract. With the singer still underage, he brought his mum to the signing.

“Can my mates be in it too?” the bold 17-year-old asked the director, and with that The Drifters, or The Shadows as they would soon be re-monickered, took their big -screen bow.

It wasn’t Cliff’s first acting part (he’d made a small appearance in a film earlier in 1959 titled Serious Charge), but Expresso Bongo – in which he was fourth billed – would be the role that announced him to the world.

However impressive Cliff is in the part, it’s Harvey that dominates the film. Though Expresso Bongo is about the emerging counter culture and the rock’n’roll explosion, it’s very much seen and judged through the eyes of the grown-ups. Despite that, it offers an authentic glimpse into how youth culture was represented at the time.

In one scene, the real-life figure of Gilbert Harding, presenting on TV, screens a clip of Bert playing, before cutting to a line-up of crusty middle-aged establishment figures who attempt to explain this new-fangled pop phenomenon.

“Now, doctor, would you say that this is a healthy sign of high spirits?” Harding asks Patrick Cargill’s besuited psychiatrist.

“It’s not as simple as that,” the doctor replies. “Adolescence in our time demands outlets for their frustrations. The drums Bongo beats may stand for someone he doesn’t like. Or they may be a simple means of evacuating tension.”

The film then cuts to a bemused looking Bongo sitting at home watching the debate. “What’s all that about?!” he exclaims.

Yet for all the sidelining of the movie’s striplings, its venom is targeted at the middle-aged exploiters of the new sound. The record producer Gus Mayer openly admits he loathes the music he makes, while even Cliff’s character appears to be contaminated by the cynicism of his elders: “It’s a bastard world and I’m a fully paid-up member.” Bongo, who starts off as likeable and relatable, becomes increasingly sneery, and by its end is so contemptuous of his fans he refers to them as “grimy yobs”.

In fact, the most sympathetic characters in the movie are both female: firstly Jackson’s stripper girlfriend, Maisie (played by Sylvia Syms) and Yolande Donlan as Dixie Collins, a middle-aged American singer struggling with irrelevance.

Expresso Bongo premiered on 20 November 1959 to generally positive reviews. Three years later, with Cliff Richard now a major star, it was re-released in a brutally cut-down version, one which, by excising many of Harvey and Syms’ musical numbers, refocused it as a Cliff flick, along the lines of The Young Ones. If you want to compare and contrast the two versions, the BFI have helpfully included both on their most recent Blu-ray release.

Looking at Expresso Bongo now, 62 years on, it’s a cherishable time capsule, offering up an intoxicating brew of espresso bars, amusement arcades and sleazy strip joints. Take special notice, when you slip in that disc, of the innovative opening sequence, where Guest’s camera prowls the streets of Soho at night, its title cards springing up on pinball machines, in jukeboxes and, for the ‘Written by Wolf Mankowitz’ credit, the man himself wearing a sandwich board.

It’s a movie that feels thrillingly seedy, at a time when many British movies were almost comically wholesome. To have one of its primary characters be a stripper, and to showcase so many striptease routines (though there’s no actual nudity in the film, there’s plenty of exposed flesh) made Expresso Bongo something of a cause célèbre at the time.

What’s especially fascinating about Expresso Bongo is that it captures London at the cusp of a new decade, and reminds us just how rapidly the entertainment industry pounced on the emerging rock’n’roll sound. And while similarly plotted American movies, such as A Star Is Born, were set among the glitz and glamour of New York’s Broadway, Expresso Bongo takes place in the squalid underbelly of late-50s London.

Guest had a talent for giving his movies an unvarnished verisimilitude (just see his bleak sci-fi drama The Day The Earth Caught Fire, made just two years later, or his double bill of Quatermass horrors) and Expresso Bongo throbs with a sense of documentary-like realism, not just of the London of the time, but for how youth culture is represented.

When the movie visits the Tom Tom Club (an obvious avatar for the 2i’s coffee bar), it’s populated by a motley collection of rock’n’rollers, beatniks and hepcats. It never feels as if this movie was written and directed by two men in their thirties and forties (Val Guest was 48 at the time).

While its songs may not be up to much, watch it for Cliff, watch it for Laurence Harvey’s playful turn as Johnny Jackson and watch it for its never-bettered snapshot of nocturnal London’s neon-drenched streets. In the 1950s, America had Rock Around The Clock and Blackboard Jungle. In 1959, we had Expresso Bongo.