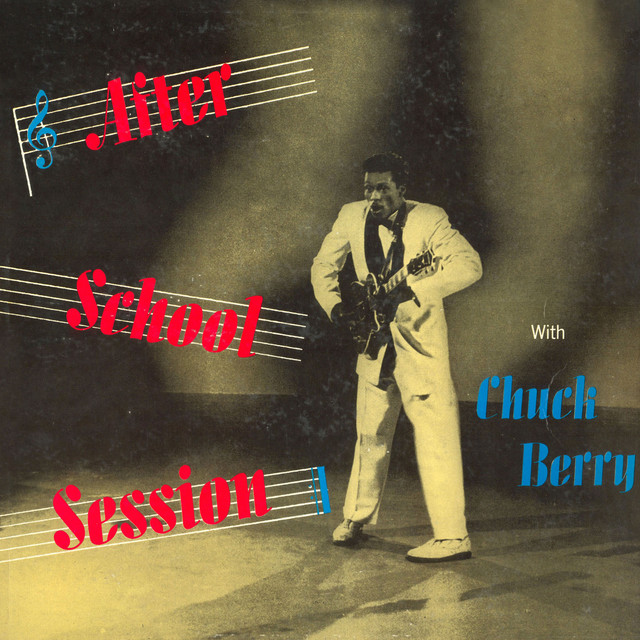

“The songs are all original compositions written by Chuck, for Chuck, and as only Chuck can perform them,” read the sleevenotes. Jack Watkins analyses one of the great albums of the late-50s, After School Session…

In the summer of 1955, Chess, a label specialising in selling R&B and blues to black record-buyers, released a new single by a still-unknown Chuck Berry. Maybellene had been recorded at the Chicago company’s South Side studios a couple of months earlier, but boss Leonard Chess had left it in the can, afraid its release might spoil sales of two other Chess singles which were doing well on the R&B charts – Bo Diddley’s I’m A Man and Muddy Waters’ Mannish Boy.

When they did get round to putting out the disc, after the urgings of New York DJ Alan Freed, it proved an instant smash, with its sales surpassing anything the label had previously achieved. Maybellene not only made No.1 on the R&B chart, it spent 16 weeks on the pop chart, peaking at No.5, giving the label its breakout from the black-only sales market into that of the more lucrative white teens.

Over the following months Chess would release a steady stream of Berry singles, including Thirty Days, Roll Over Beethoven and School Day (Ring! Ring! Goes The Bell). However, they didn’t exactly rush to cash in on the album market. Berry’s first effort After School Session did not come out until May 1957, the sleevenotes hailing him as “Rock-a-Billy Troubadour”.

The Poet Laureate Of Rock’n’Roll

In reality, in the days when the money was in singles not long players, Berry hadn’t gone into the studios to ‘cut an album’ in the modern sense. The 12 tracks were lifted from the tapes of six sessions spread out between May 1955 and January 1957 – and some buyers at the time may have been disappointed at the omission of Maybellene and Roll Over Beethoven, and the fact that it included only three real rockers, School Day, Too Much Monkey Business and Brown Eyed Handsome Man.

Yet Berry was never, in his own mind at least, just the swaggering, duck-walking, guitar-toting pioneer of straight-down-the-middle rock’n’roll that some painted him as being. John Lennon once said that if you’d tried to give rock’n’roll a name, you might have called it Chuck Berry, and that, musically speaking “before Elvis, there was nothing”, but Chuck knew better. When he walked into the studios and hitched the strap of his Gibson ES-350T over his shoulder to record School Day in 1957, he was already 30 and effectively from a different generation to the likes of Presley, Gene Vincent, Jerry Lee Lewis and Eddie Cochran, all at least nine years younger. He knew that raucous, uptempo music didn’t just begin when Elvis, Scotty Moore and Bill Black walked into the Sun Studios in 1954.

Born in 1926, Berry had grown up in a respectable neighbourhood of St Louis, Missouri, listening to swing-era giants like Lionel Hampton and Tommy Dorsey. His guitar heroes were sophisticated jazz operators like Charlie Christian, who played in both Benny Goodman’s big band and his bop-pioneering sextet, and Carl Hogan, a member of Louis Jordan’s Tympany Five. As far as Berry was concerned, as he told Goldmine in 1983, Jordan “was playin’ it [rock] long before me, Fats, any of us.”

Signature Sound

He also loved the songs of hillbilly performers like Kitty Wells, and Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, and admired the pioneer of electric blues, T-Bone Walker. When he made his first professional performance as a member of boogie pianist Johnnie Johnson’s Sir John’s Combo at the Cosmopolitan Club in East St Louis in 1952, he recalled he was playing more “blues than rock”. He even hankered to be a crooner in the style of Nat King Cole. What Berry, unlike his more stilted heroes, appreciated was the visual side of music, and that youngsters wanted “some gettin’ down, and some wigglin,” as he put it – but After School Session with its stylistic diversity might well be the album he’d personally chosen as reflecting his rich musical heritage.

Even so, the LP had plenty of examples of what are now regarded as his signature riffs. The biggest track, chart-wise, was School Day (Ring! Ring! Goes The Bell), which had already been released as a single, reaching No.3 in the pop chart in April 1957, Berry’s highest placing up to that point. It hasn’t impressed all his biographers and critics over the years. Fred Rothwell, author of the authoritative Long Distance Information: Chuck Berry’s Recorded Legacy, felt that, “deliberately tailored for the white teenage market, it doesn’t quite ring true”. Even so, it had an irresistible shuffle beat and featured Berry’s anthemic line: “Hail! Hail! Rock’n’roll,” which would be the title of a documentary on his career in 1987.

The classic bell-like guitar intro to School Day may sound like pure Chuck, but it’s also an example of how much he owed to his collaborator and original mentor Johnnie Johnson, whose boogie woogie piano was an integral, though often overshadowed, part of his sound. Johnson later recalled how, when they came to record the track, they struggled to find a suitable intro. In a moment of inspiration, Johnson suggested lifting the short intro of an old song by 1920s boogie man Meade Lux Lewis called Honky Tonk Train Blues: “That was supposed to sound like a train whistle,” he remembered. “Well, when Chuck played it on guitar, we thought it sounded like a school bell ringin’.”

Guitar Hero

If Berry’s jangly guitar interjections on School Day, achieving a call-and-answer effect with his vocal, are memorable enough, Brown-Eyed Handsome Man is an undoubted masterpiece, with semi-autobiographical overtones. For ‘brown- eyed man’, read ‘black man’, as near as you could get in the still colour conscious US of the 50s to an “I’m black and I’m proud” statement – though that didn’t stop Buddy Holly cutting a more than respectable demo in Clovis, New Mexico in 1956, which, with overdubbing by the Fireballs, became a much bigger hit, in the UK at least, in 1963.

If some of Berry’s mould- shaping rock riffs were actually ‘borrowed’ from the likes of Carl Hogan – though delivered with the visceral attack that makes the Berry Chess recordings sound so elemental – his lyrical awareness and wit was surely sharpened by listening to Louis Jordan. The jump blues maestro brilliantly utilised jive talk on such songs as Beware! and Open The Door, Richard, inventing words such as “obnoxicated”, just as Berry would give us “motorvatin’” in Maybellene. And No Money Down was Berry’s take on the street-savvy young black dude, turning the tables on a would-be-slick car salesman to “head on down the road” in his power-steering convertible De Ville.

Although Berry wasn’t alone in waxing lyrical about cars – the subject had become a theme in rock’n’roll almost instantly with Jackie Brenston/Ike Turner’s Rocket “88” in 1951 – automobiles would form a strong part of Berry’s songs, from Maybellene to his 1964 hit No Particular Place To Go.

Still Stands Up

For all the glory of his guitar – which had a thicker, rougher sound than many great players of the time, like the stinging Telecaster of James Burton or the nimbler, jazz-toned playing of Cliff Gallup – it was Berry’s lyrical skills that really made him different. Chuck certainly never wrote anything better than three of the songs on After School Session, namely Brown Eyed Handsome Man, No Money Down and Too Much Monkey Business (the latter also includes one of his greatest guitar breaks – listen to the thrilling way his solo suddenly seems to catch fire after the fourth verse). But Johnnie Johnson, present on most of his recording sessions, would later file a lawsuit claiming co-authorship of 57 Berry songs.

The case was thrown out, but one track on After School Session clearly bears Johnson’s imprint – Wee Wee Hours, an atmospheric blues-at-midnight type piece, knocked out by Berry and Johnson in 15 minutes at the same session as Maybellene. Johnson had actually expected “a serious blues label like Chess” would go for it as the A-side. Johnson would also contribute a lovely Chinatown flavour to the rhumba-rhythmed album closer Drifting Heart.

In fact, After School Session was a multi-flavoured Berry album, from the Caribbean patois of Havana Moon to the narrative drama of the uptempo country ballad Downbound Train, while retaining plenty of classic rockin’ touches. And over 60 years later it still stands up.

For more on Chuck click here

Read More: Classic Album – Chuck Berry Is On Top