Rock’n’Roll Rehab – Liquorice John Death: Ain’t Nothin’ To Get Excited About

By Steve Harnell | December 20, 2022

Performing under a unique yet poignant pseudonym, Procol Harum kick out the jams with an under-the-radar gem of 50s rock’n’roll…

What’s the first thing that springs to mind when you think of Procol Harum? For most, it’s Matthew Fisher’s iconic Hammond organ introduction that ushers in arguably the most beloved psychedelic song of all time, A Whiter Shade Of Pale – they were the band that skipped the light fandango and turned cartwheels across the floor with their debut single in 1967.

Procol connoisseurs may even point to their multi-part epic In Held ’Twas In I, the band’s classic album A Salty Dog, or even the vaulting ambition of their 1972 live LP that saw them hook up to fine effect with the Edmonton Symphony Orchestra. Their talent for 50s rock’n’roll then may have escaped your attention.

Like many of the patchouli-scented bands of their era, Procol Harum did not arrive as fully-formed prog-psych conquistadors – they had a back story beneath the surface, forming from the ashes of Southend-on-Sea R&B group The Paramounts.

Dispirited by an inability to follow up their Top 40 hit cover of Leiber and Stoller’s Poison Ivy, Paramounts frontman Gary Brooker considered retiring to focus on penning material for other artists. Yet when his friend Guy Stevens – later to produce Mott The Hoople and The Clash – introduced Brooker to lyricist Keith Reid, the pair formed a songwriting team.

With no initial takers for their work, Brooker devised Procol Harum to perform the duo’s material. The rest was history – and in the case of A Whiter Shade Of Pale, a track that’s gone on to become the most played song of all time on UK radio.

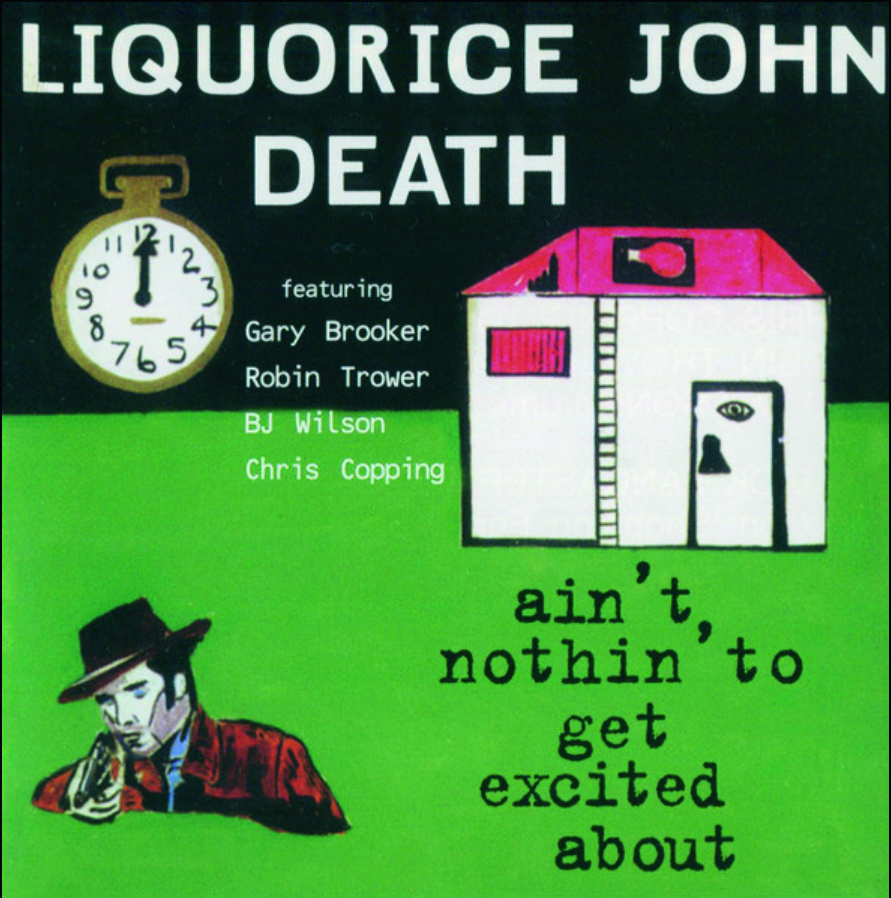

Yet Procol Harum’s roots as an R&B band would have a direct influence on one of the most intriguing and overlooked entries in their back catalogue: the rock’n’roll covers album Ain’t Nothin’ To Get Excited About. Never intended for formal release and recorded under the pseudonym of Liquorice John Death, the resultant LP disappeared into the ether and took 27 years before finally resurfacing

The album’s genesis came from rather perfunctory circumstances. In 1970, while preparing to record their fourth studio LP, Home, producer Chris Thomas suggested that the band should warm up with some old chestnuts while Abbey Road engineers set up their equipment.

At this point, Procol Harum’s line-up had essentially coalesced to the same as former incarnation The Paramounts, so a dip into that band’s road-hardened setlist of 50s rock’n’roll seemed the perfect choice.

In the liner notes to Ain’t Nothin’ To Get Excited About ’s eventual release in 1997, Thomas explains that the impromptu warm-up was a neat way to introduce some momentum to the session: “When you’re about to cut a new track and you just need to get on with it, you don’t really want the producer to ask the drummer to hit the snare drum for the next 15 minutes in order to analyse or correct what needs to be done.”

The ad hoc rock’n’roll set-up was such a resounding success that Procol reconvened at Abbey Road a few months later to recapture the spirit of those improvised performances, rattling through an astonishing 45 songs in one 12-hour session from 7pm to 7am.

Although many of the selections remained incomplete, Thomas had enough finished for a 13-track album. Brooker’s vocals were put through a PA in the studio with Blodwyn Pigs’s sax player Jack Lancaster supplementing the original Procol quartet.

Procol’s unusual pseudonym, Liquorice John Death, was suggested by their friend, session singer Dave Mundy, who was also responsible for the album’s hand-drawn cover. Mundy committed suicide in 1970 and left possessions to Procol’s guitarist Robin Trower, which included prospective artwork for the Liquorice John Death LP.

In 1995, Brooker explained to Record Collector: “[Dave] jumped off a 50-storey building at some point. Out of respect for him, we used [Liquorice John Death] for the session, and also wrote a song called For Liquorice John on our Grand Hotel album in 1973.”

Chris Thomas adds in the LP liner notes: “Sometime later during the construction of Air Studios in Oxford Circus they were giving the Neve desk in No.1 a trial before the studio area was completed. I took the [Liquorice John Death] tapes in and mixed about a dozen of my favourites and made a seven-and-a-half inch copy for myself.”

In the mid-70s, Thomas lent his copy of the tapes to Capitol Radio’s Roger Scott for broadcast purposes. And that was the last time anyone heard the fruits of those 1970 sessions until Brooker found his own copy in the late 90s and realised he’d stumbled across something rather special.

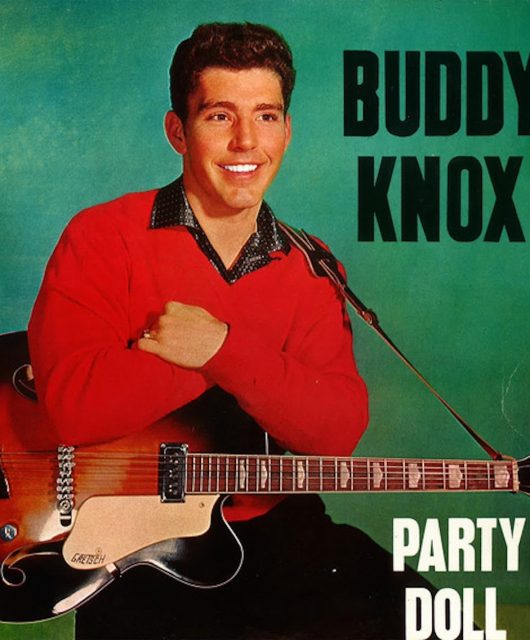

He must have been delighted at his own performance once he listened back to the tapes. Brooker is on rollicking form on opener High School Confidential, both vocally and pounding the 88s, with Robin Trower also throwing in some burning solos. While not renowned as a heavy-hitting rock band, there’s a real thump to Procol Harum’s take on Kansas City and Brooker rips up his vocal cords on a raucous Lucille.

The frontman’s affection for Little Richard similarly shines through on The Girl Can’t Help It and Keep A Knockin’. Meanwhile, there’s a brooding menace to a fearsome reinterpretation of Brand New Cadillac and old rockabilly standard Matchbox is given added heft.

With the preponderance of high-octane piano tunes here, Brooker was surely leading the charge – his version of Fats Domino’s I’m Ready in particular swings like a beast. There’s an authenticity to the rockin’ covers as well as a lightness of touch to the retread of The Coasters novelty R&B hit, Shopping For Clothes.

Procol Harum may have been slipping into another costume for Ain’t Nothin’ To Get Excited About but it proved to be a perfect fit. Time to retrieve it from the wardrobe and get it out of mothballs…