His underground classic Rockin’ Bones was released in 1959, but Ronnie Dawson had to wait until the 1980s to gain true acclaim. Vintage Rock profiles the late, great Blond Bomber… and speaks to those who knew him best… By Julie Burns

Ronnie Dawson was a rare rocking talent who seemed to operate in reverse: the man known as the Blond Bomber actually got better as he got older.

He achieved regional success in his native Texas back in the 1950s, but it was between 1988 and his premature passing in 2003, that the singer enjoyed heroic cult status across Europe’s revivalist circuit. While many of his peers’ careers had packed up early, Ronnie burned more brightly second time round.

“Ronnie’s UK fans were very important to him,” his wife, Chris, tells Vintage Rock today. “He received more recognition from those fans than he ever received here in the US. Actually, all over Europe he was more appreciated than at home. I am so grateful for that, as was he.”

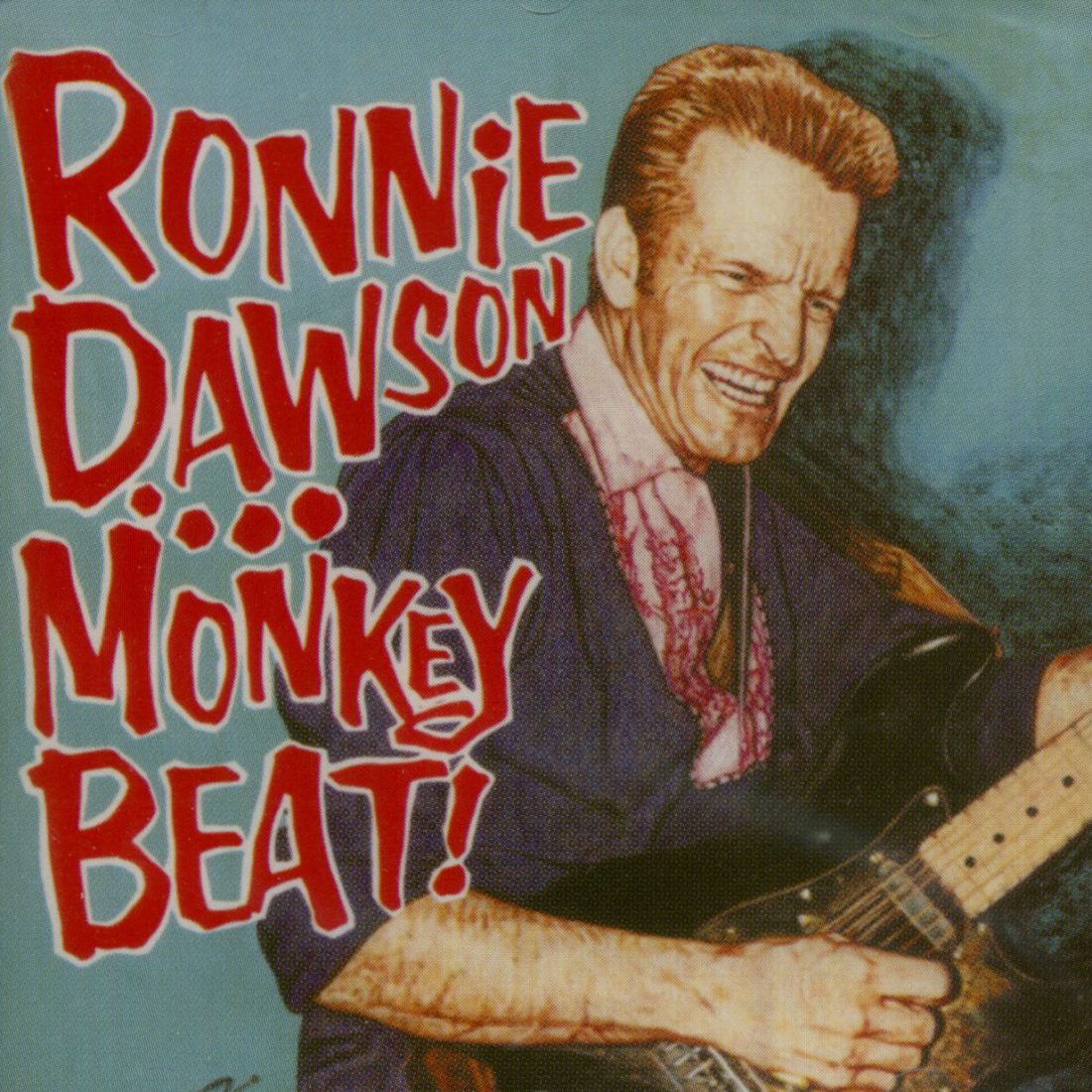

With a handful of hot albums including Monkey Beat (1994), Just Rockin’ And Rollin’ (’96), and Live At The Continental Club (’98), Ronnie returned with a bang. From London to the Netherlands, cuts such as Still-A-Lot-Of-Rhythm, Rockinitis and the wildly urgent Up Jumped The Devil became UK clubs’ bopping anthems in those later years.

Visit any European real roots r’n’r club today, and it remains the case. Dawson’s raw, rhythmic and kinetic tracks sounded like a more subversive version of the 50s, and packs a mean contemporary punch.

It must have seemed surreal to receive the adulation that he deserved so late in his career. Yet according to collaborator guitarist Tjarko Jeen, “Ronnie didn’t consider his albums a comeback as such – he just saw them as a continuation of what he considered to be unfinished business.”

That unfinished business began when, out of the blue in 1986, No-Hits Records founder Barney Koumis knocked on Dawson’s door at his apartment in Dallas, Texas. Koumis was already a major DJ on London’s rockin’ scene, and essentially brought Dawson back from the wilderness in 1990 by releasing the Rockin’ Bones compilation album.

Co-producing a clutch of subsequent new recordings with Ronnie, Koumis was integral in helping him pick the right material and musicians (such as The Polecats’ Boz Boorer) and getting him exposure that spanned John Peel recording sessions at the BBC in 1993, performing on the Conan O’Brien primetime American chatshow, playing at Carnegie Hall; and later Yep Roc recordings that featured in the movies Primary Colors and Simpatico.

On his Rockin’ Bones CD liner notes, Dawson confessed to having been “a wallflower” in his pre-musical youth, but by the 80s and 90s, he transformed onstage into wildfire personified. Importantly, he was still evolving and generating fresh material.

Uniquely relevant to the rockabilly revival, Dawson delivered real rockabilly with a distinctly modern twist of hard blues, country and garage rock. His vocal was unique in markedly improving with age, lending a gruff, rugged swagger to that startling, scorching sound.

Fans still wax lyrical online, describing his music as “just the way this stuff should be – rough, edgy, and sounds like it was recorded in someone’s bathroom.” Elsewhere they say it was “like being hit by a truck, in a good way”, or the definitive “If this doesn’t move you, you’re dead.”

Flashback to the 1950s, and Dawson had nearly made it big back then, having first formed a band in ’56, and appearing on the popular Big D Jamboree talent show in his local Dallas, Texas.

As he explained to the Phoenix New Times in 1995, “If you won the contest 10 times, you were invited to be a regular on the programme, and they would offer you a recording contract… I won 10 times, and in three months I was looking at a record with my name on it.” In terms of screaming girls, he held his own against other upcoming Big D acts of before, including one Elvis Presley.

Billed as Ronnie Dee & The D-Men, Dawson signed to the R&B-oriented Back Beat label and delivered Action Packed b/w I Make The Love in 1958. Despite a lengthy promotion – even a place on an Alan Freed package tour – the single only gained scattergun airplay, as did 1959 release, Rockin’ Bones, this time credited to Ronnie Dawson ‘The Blond Bomber’. But despite only ripples back then, both tracks are today regarded as highly influential.

After a spell playing sock-hops with Western swing group the Light Crust Doughboys, Ronnie shared the same manager as Gene Vincent and toured nationally with him. By 1960, he witnessed Vincent’s American career nosedive as rock’n’roll turned into teen-tuned pop. With his boyish voice and cute platinum blond crew cut, 21-year-old Ronnie was primed for teen-idol stardom.

Signing with Dick Clark’s Swan label, he cut two pure poppers: Summer’s Comin’ and Hazel, showcasing both on Clark’s famous American Bandstand TV show. But just as his career was about to be pushed, the Payola scandal hit, and Clark had to get rid of his non-Bandstand interests. Ronnie later reflected this did him a favour, in taking his music in his own direction.

Recording under various guises as Johnny And The Jills, Snake Monroe, and Commonwealth Jones for Columbia and Do-Boy, he also played drums on sessions including Bill Channel’s Hey Baby, and Paul & Paula’s Hey Paula. Mid-60s, he joined Dallas based folk/blues band The Levee Singers, who were successful enough to guest across network TV. By the early 70s, Ronnie established a Buffalo Springfield-style country-rock band Steel Rail, which he juggled with a more lucrative line in food and drink jingles.

Come 1977, and the death of Elvis triggered a renaissance of interest in rockabilly’s originators. Thanks to psychobilly group The Cramps’ 1981 recording of Ronnie’s Rockin’ Bones, interest grew in Dawson’s back catalogue. Riding a wave of reissued recordings, he embarked on his first ever tour of England in 1986. Reflecting on the sensational reaction, he said, “All these people started embracing me. It was heaven. I didn’t want to go home.”

Mid-90s, exciting new material for Koumis’ No-Hits label (leased to Crystal Clear in the US) followed. Ronnie mentored promising new acts, notably his own support crews – The Tin Stars and High Noon – plus Boz Boorer and The Frantic Flattops. In 1999, came More Bad Habits (Yep Roc), his final album. Keen to keep pleasing his fans, the inveterate trouper continued to work. He toured as and when, despite the onslaught of cancer, and in 2003, at the age of 64, went out just as he’d come back: like a light, in true rebel rocker spirit