It may have missed out the big hits, but Jerry Lee’s long-playing debut showed his extreme versatility, from rockers to ballads… and even a traditional gospel number. Jack Watkins listens back to a Sun classic…

Sam Phillips didn’t set much store by long-playing records. His policy at Sun was geared to producing singles, which were cheaper to make, and offered the prospect of quicker returns and a more regular cash flow for his tightly budgeted operation. And it’s fair to say that Jerry Lee Lewis, one of the most instinctive and uncalculating performing artists in popular music history, never gave the matter much thought either.

It’s no surprise, then, that Jerry Lee’s eponymously named debut album, released in 1958, has sometimes been disparaged as a slackly assembled hotchpotch. Criminally, in some eyes, it even omitted to include the Killer’s two monster hits of the previous year, Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On and Great Balls Of Fire, the singles which had marked his commercial breakthrough, and which revealed him as the most likely of the Sun rockers to fill the label’s charisma vacuum left by Elvis Presley’s departure for RCA.

But while the absence of these songs was definitely an own goal by Phillips, speaking volumes about his disregard for the LP market, the passage of time lends a more favourable perspective. Not only is Jerry Lee Lewis now highly collectible, but it also provides an early hint of the deep well of influences and material from which the Ferriday Fireball would draw upon, not only during his Sun years, but across his entire career.

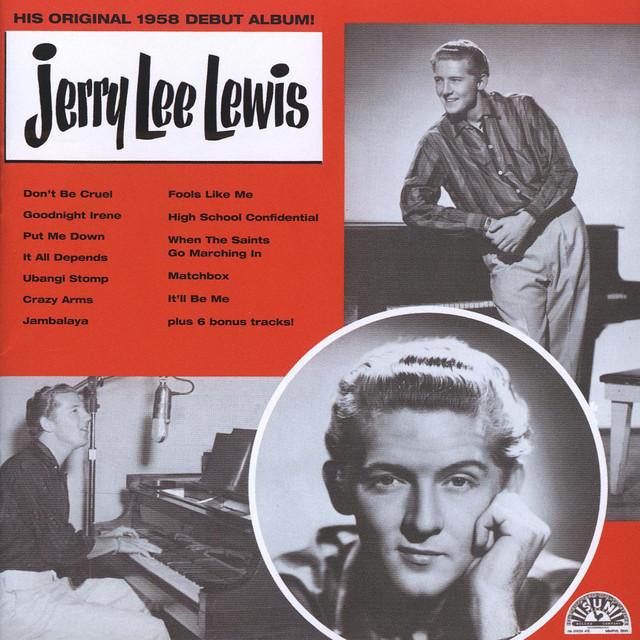

As well as that, the timing of its release now seems highly poignant. You could even imagine the Killer looking at his boyish face on the sleeve now and reflecting back on those times with a tinge of sadness, a sense of what might have been – because when it arrived in the record racks in the spring of 1958, he was riding the crest of the wave, his records charting in Europe, and just about to depart on his first international tour.

But, within a month, the British press would slay him for his marriage to his 13 year-old cousin Myra, and the tour would be aborted after just three shows. The negative headlines followed him all the way back across the Atlantic, and pretty soon his stateside career would be in bitter decline, too. Jerry Lee never faded into oblivion, but it would take years for him to repair his standing after such concerted character assassination, and he never truly recovered from the experience.

If there’s one major criticism that can be levelled at the album, the tracks for which were drawn from a series of Union Avenue studio sessions from late 1956 to the spring of 1958, it is that many of the offerings are of songs more readily associated with other artists. But in Jerry Lee’s case, this matters less than with most singers, since no performer was less interested in making stale, faithful remakes.

Throughout his career, he has shown a remarkable capacity to take old songs and make them utterly his own so that, even when the original is as essential as, say, Little Richard’s Good Golly Miss Molly, or Hank Williams’s Cold, Cold Heart, they are transformed into something bearing Jerry Lee’s unmistakable signature.

And while the disc wasn’t exactly wall-to-wall with barn burners, the track list did include one of his greatest rockers, High School Confidential, which also turned out to be his last major hit single. The number was written by Ron Hargrave, and was the title song from a movie starring the pneumatic blonde Mamie Van Doren, directed by mid-’50s pulp sci-fi maestro Jack Arnold (It Came From Outer Space, Creature From The Black Lagoon, The Incredible Shrinking Man).

The film would have been unmemorable were it not for the appearance of Jerry Lee, backed by the pair who formed his road band, his bass-playing uncle JW Brown and drummer Russ Smith, belting out the aforesaid song on the back of a flatbed truck.

With its ’50s teen references to high school hops and boppin’ shoes, on the face of it you might think this was one of Jerry Lee’s more dated rock’n’roll confections. Not a bit of it. His opening declamation: “Open up a-honey, it’s your lover boy me that’s knockin,” followed by three hammer blows at the piano – simultaneously echoed by Sun session man JM Van Eaton’s drums – is one of the great moments in the Ferriday Fireball’s recording career, and there are quite a few of those to choose from.

It’s quintessential Killer in his swaggering pomp, the boyfriend every parent dreaded rolling up to their front door to sweep away their daughter. What follows is delirious, barely controlled mayhem, with Roland Janes’ electric guitar ringing like a delinquent school bell and tussling for attention with Jerry Lee’s stabbing chords.

Janes and Van Eaton would accompany Jerry Lee on a large proportion of his Sun recordings, the chemistry between the trio seemingly being instantaneous, and they were present at his very first session on November 1956. This date yielded Crazy Arms; hearing just a few bars of this song had convinced Phillips to sign the confident young man from Louisiana who’d walked into the studio boasting that he could play his piano the way Chet Atkins played the guitar.

The track is on the album, and you can only marvel at the assured way he seized the honky tonk hit – already one of country music’s classic shuffles, as sung by the great stylist Ray Price – and made it his own, breaking up the lines, and stretching syllables for maximum soulful effect. It was also his first Sun single, credited to “Jerry Lee Lewis with his Pumping Piano”.

It would be a country song, Another Place, Another Time, recorded for Mercury in 1968, that would spark Jerry Lee’s late ’60s revival, but this wasn’t a piece of career opportunism shaped to exploit the growing popularity of the genre towards the end of that decade. Country ballads had been part of his repertoire before he even walked through the doors at Sun, and there’s no better example on Jerry Lee Lewis than Fools Like Me, executed with impeccable gravity, and so good it had been the flipside of the High School Confidential 45rpm. Roy Orbison was one of the backing vocalists.

It All Depends – fully entitled It All Depends (On Who Will Buy The Wine), but abbreviated on this LP’s sleeve and centre label – was another sombre ballad whose concerns were about as far removed from rock’n’roll’s teenage kicks as it was possible to get. Jerry Lee’s voice had not yet acquired a weathered air, yet he sang lines like “Not long ago you held our baby’s bottle/But the one you’re holding now’s a different kind” with the conviction of a veteran. Listen, too, to the way his left hand on the piano anchors the song in the manner of a bass player.

Given that he covered so much of the music of Hank Williams in his time at Sun, it’s no surprise that he kicks off side two of the album with one of his hero’s songs. But whereas Hank Williams sounded like he was in a pit of dejection, it was the trick of “rock’n’roll’s first wild man” to sound resilient, to discover chinks of hope in the lyrics of country music’s finest manic-depressive. So Jambalaya, which was always one of Williams’ more upbeat numbers anyway, was amped up and transformed into a good-natured semi-rocker.

Other high quality rockers on the album included lively takes on Otis Blackwell’s Don’t Be Cruel, the Warren Smith hit Ubangi Stomp, and Matchbox, whose origins lay in a composition by 1920s bluesman Blind Lemon Jefferson, but which had been reworked to devastating effect by Jerry Lee’s labelmate Carl Perkins. But if there’s one ‘undiscovered’ rocking classic on the album, it’s surely Put Me Down, a lean-hipped shaker which showcases Jerry Lee’s piano and the understated guitar of Roland Janes, who also wrote the song.

Proving that, even in his early twenties, Jerry Lee had an astonishing ability to absorb and then refashion songs from the past, the album also featured his take on Leadbelly’s folk number Goodnight Irene, and the aged gospel standard When The Saints Go Marching In. But it’s a measure of how what turned out to be music history was being made on the hop in the late ’50s in that Sam Phillips reckoned the track It’ll Be Me shaped up as the bigger potential hit when it was released on the opposite side of Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.

At the recording session Jack Clement had certainly been far more interested in getting Jerry Lee to record former song, which Clement had wrote himself while sitting on the toilet, contemplating reincarnation. “That’s a hit,” he announced to the rising star, once he’d got his precious song in the can. “Now what do you want to do for the flip?”

It’ll Be Me is certainly a good tune, with Jerry Lee’s piano rumbling away beneath an amusing lyric, but fortunately Phillips eventually recognised the alternate side for the monster it was, putting his full weight behind it, and getting Jerry Lee a slot on The Steve Allen Show.

By the time Jerry Lee Lewis came out, the artist was a headliner on the point of a massive fall. In time, he’d recover and issue many far more skilfully conceived albums. But his opener for Sun doesn’t just play like a great start to a long career. These days, it’s a reminder of the moment when he really did appear to have been blessed with the Midas touch.