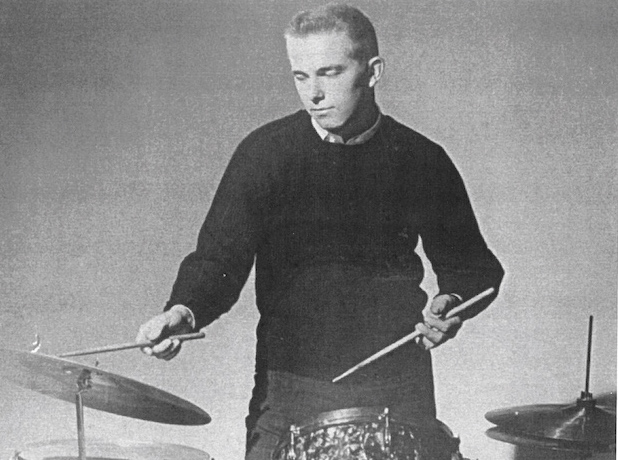

Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, Charlie Rich, Johnny Cash and Billy Lee Riley all began their careers at Sun Records – and one man kept rhythm for all of them. In 2019, we met rockabilly’s greatest drummer, JM “Jimmy” Van Eaton. By Douglas McPherson

People don’t always realise that Great Balls Of Fire is a duet. The rock’n’roll classic features no lead guitar or bass. The only musicians on the disc are Jerry Lee Lewis on vocals and piano, and Jimmy Van Eaton on drums.

“I’m not sure how that happened,” Van Eaton admits, more than 60 years after laying down the track. “We actually cut the song with the full band for the movie Jamboree, but with a lot of that stuff you didn‘t know which take they were gonna release. They would sit down later and listen to ’em and pick different cuts.”

There’s no doubt, however, that the Killer’s pumping piano and Van Eaton’s drums are the perfect match.

“I always said it was meant to be,” Van Eaton says. “My drumming and his piano playing – his left hand – just fit like hand in glove. We kinda knew where we were going with it. I knew when to stop and when not to stop. It worked out pretty good.”

JM ‘Jimmy’ Van Eaton was born and raised in Memphis and began his musical career in junior high school.

“You had to take either a vocal or instrumental class for at least a year,” he recalls. “I got in the junior high school band and played trumpet for a year. That didn’t work out so well, so in the eighth grade they switched me over to drums and I just fell in love with them.”

By the ninth grade, Van Eaton and some school friends had formed a Dixieland band called The Jivin’ Five.

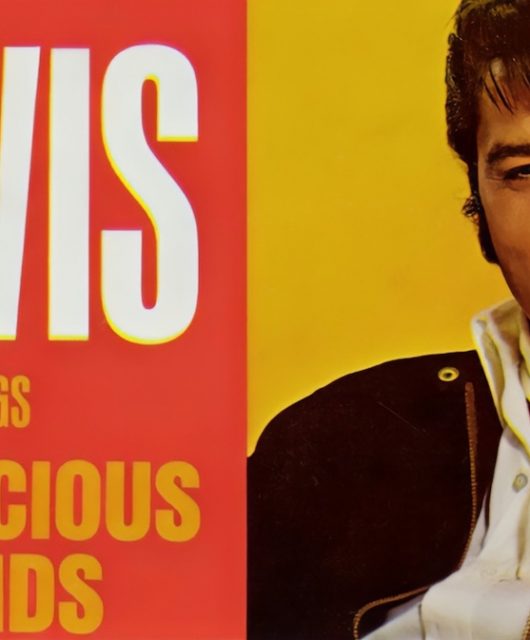

“This was before Elvis. We were listening to big bands like Tommy Dorsey and his Orchestra. Then Elvis came along and I wanted to be a rock’n’roll drummer, so I kinda forgot about Dixieland and started concentrating on rock’n’roll.”

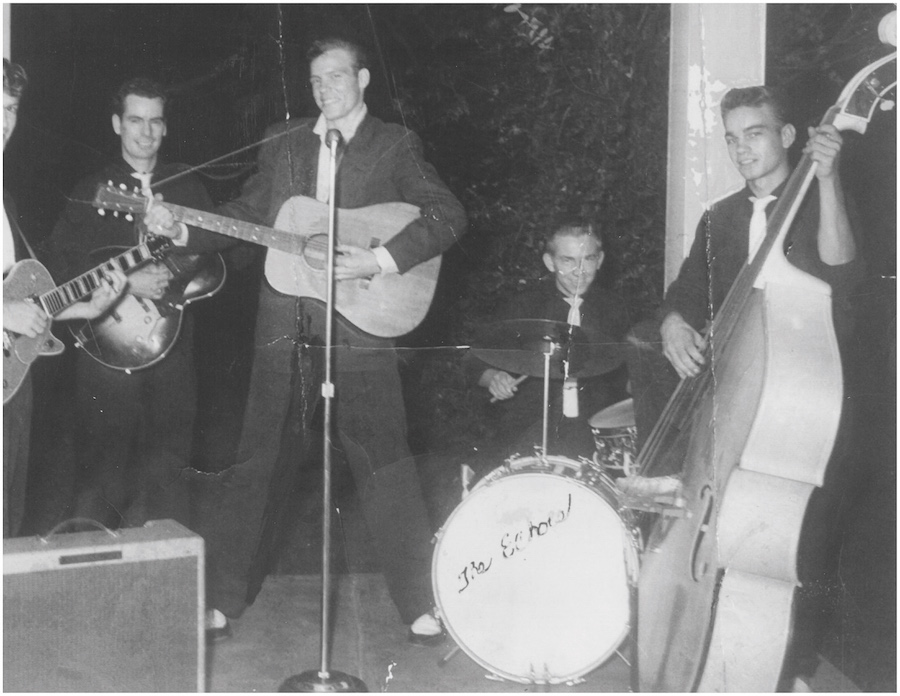

His next band, while he was still in high school, was The Echoes. It was “an Elvis type of band” and he decided to follow in Presley’s footsteps with a trip to the Memphis Recording Service at the Sun studio on Union Avenue.

“I wanted to hear what we sounded like and you could go in, like Elvis did, and cut an acetate dub,” Van Eaton explains. “I think they charged me $15 to cut two sides.”

The engineer was Jack Clement who had recently produced Trouble Bound by Sun’s latest signing, Billy Lee Riley.

“After the session, Jack asked me what my plans were,” Van Eaton continues. “I said I didn’t have any and he said Billy Lee Riley needs a drummer, would I be interested? So Jack and Billy and a guitarist called Roland Janes came out to hear me play at a little club with The Echoes. They hired me and the bass player, Marvin Pepper, to go and work for Riley.”

Van Eaton’s kit at that point, and throughout his time at Sun, was a set of black pearl Gretsch drums that he

bought new.

“I didn’t come from a wealthy family,” he says, “but I had a job when I was going through high school and saved up about $500 or $600 over a three-year period. I wanted to buy a used car, because when you’re a senior in high school and you’re still walking around… if you had a car, you really had something. Then I saw this set of drums and instead of buying a car, I spent that $500 or $600 on the drums.”

It proved a wise investment. “They were shiny and looked good,” he remembers. “I used to laugh and say

I probably got more gigs because of my good-looking drum set than my playing. Then, shortly after that, the drums bought me a brand new car!”

As well as playing live with Riley, Van Eaton began practising and recording with him at Sun where he was soon established as the house drummer alongside guitarist Roland Janes, whose stinging licks were as much a part of the Sun sound as the studio’s trademark slap-back echo.

“I had a music scholarship to go to the University Of Memphis, but I started recording when I was still in high school, so I didn’t see the point in going to college to learn how to do what I was already doing,” Van Eaton chuckles.

The first released song that he played on was Jerry Lee Lewis’ debut Crazy Arms. Recalling his first meeting with the fledgling fireball from Ferriday, Louisiana, Jimmy lets out a chuckle. “Oh man, I didn’t know what to think about Jerry Lee. He didn’t look like any rock’n’roller we’d ever seen. Elvis, Billy Riley and Warren Smith all looked like we thought rock’n’rollers were supposed to look like, but Jerry Lee came in with a whole different deal. He had a goatee. My first impression was I didn’t know what to think about him.

“I didn’t think he was going to be worth our effort, but I have to say he’s probably the most talented guy I ever played with. Once I saw what a great singer and fabulous piano player he was I looked forward to anything we were gonna do with him, because I knew it was going to be fun and different.”

As to Lewis’ larger-than-life personality…

“He was always cocky,” Van Eaton states. “He always thought he was the best and he would try to prove it to you. That’s why, when those box sets eventually came out, there were so many outtakes. He thought he could out-sing Elvis, so we did Don’t Be Cruel and Jailhouse Rock and all those songs just because he wanted to show me he could do them as well as Elvis.

“Jerry could do just about any kind of music he wanted to do,” the drummer continues. “He could take songs that had already been recorded and make them sound like fresh new records. Crazy Arms, his very first record, was a cover of a Ray Price record, but when Jerry did it, it didn’t even sound like the same song.”

Crazy Arms was only a local hit and Lewis for a while joined Van Eaton as part of the Sun house band. On records like Hayden Thompson’s Love My Baby and Billy Lee Riley’s Flying Saucer Rock’n’Roll, you can hear the way that Jerry’s pumping piano and Jimmy’s drumming mesh together to become the perfect rhythm machine.

Lewis’ rise to the big time came when he recorded Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On in 1957. Van Eaton was right beside him on the drums and recalls how the multi-million seller came about.

“We’d played a club about a week before. It was a four-hour club gig from 9pm to 1am. This was when Jerry was just getting started and I didn’t know if we even knew enough songs to play for four hours. So he started playing Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On, which he said he’d been playing in a club down in Louisiana. I’d never heard it before, so we started playing it, just by ear. The dance floor started filling up and then a bit later they’d come up and say, ‘Play that Shakin’ song again.’ We probably played it three or four times that night and every time we played it, the floor would fill up with people.

“So we knew they loved the song, but we didn’t think about recording it until we were working on what turned out to be the B-side, It’ll Be Me, which Jack Clement had written. We worked on It’ll Be Me for about three hours and we were getting stale, so Jack said, ‘Let’s stop and try something else.’ Somebody said, ‘Let’s put down that song that everybody liked the other night.’ So we played Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On in one take. That’s the record they released, and the rest is history.”

Another legend Van Eaton played with was the Man In Black, Johnny Cash.

“Cash was a kind of bigger-than-life guy – he was a tall guy,” Van Eaton remembers. “But he was a nice guy. He was always nice to me.

“Johnny didn’t use drums until Jack Clement started recording him. Jack wrote I Don’t Like It But I Guess Things Happen That Way and Come In Stranger and that was the first time Cash had recorded with drums, piano and backing singers, as opposed to just the Tennessee Two. I don’t know if Cash liked it or not. I don’t think he wanted a drummer. But once he got accustomed to using drums he wanted a drummer in his band, so he hired WS Holland on the road and WS played with him all his life after we cut those Sun records.

“The one with the most drums on was Straight A’s In Love,” Van Eaton adds. “That’s one you can actually hear me playing on.”

Van Eaton’s first musical hero, Elvis, had moved on from Sun to RCA before Jimmy began drumming there, but it wasn’t uncommon for him to return to the little studio where he had made his first recordings. The most famous occasion, when Lewis, Cash and Carl Perkins were also present, was immortalised on disc and in an iconic photograph as the Million Dollar Quartet.

According to Van Eaton, “Elvis would pop in all the time. When he was in Memphis, he would love to come and hang out at the studio. There were very few places that Elvis could go and not be bothered, and the studio was one of them.

“Elvis, before he went into the army, was very accessible. He liked to hang out with us. One of my favourite Elvis memories was that I went out to his house on Audubon Drive one night. There wasn’t anybody there but his mother, his daddy and four or five other people. He sat at the piano and gave us a personal concert and it was great. At the time you don’t think anything about it, but I look back now and realise how special that was.”

What were the sessions like at Sun? Was it all smoking and drinking?

“There was a lot of smoking,” Van Eaton confirms. “I never did smoke and I don‘t remember Jerry Lee smoking all that much, maybe a cigar, but all those other guys seemed to smoke. They would do their share of drinking, too, but we didn’t do a lot of drinking during the sessions. I’d say of all the sessions we did, maybe half a dozen was more drinking than there should have been. Like the night we cut Down The Line with Jerry Lee and the night we cut Thunderbird with Billy Riley. Some of those sessions had a few adult beverages!

“But there wasn’t as much drinking as people would have you believe, because most of this stuff was cut during the day – it was mostly in the afternoon.

“We didn’t do a lot of night sessions,” the drummer continues, “but when we cut Raunchy with Bill Justis, we didn’t even start the session until 2am. Bill had a gig at the Peabody Hotel that night with his big band, and I was playing with Riley at the Starlite supper club and didn’t get off until 1am. So we all met at the studio after those gigs. We had three guys out of Bill Justis’ orchestra and three guys out of Billy Riley’s band: Roland Janes, me, and Jimmy Wilson, the piano player.”

The result was another million seller, a twangy instrumental released on the Sun subsidiary Phillips International

that reached No.2 in the US and No.11 in the UK.

The tight confines of the Sun studio meant that the musicians had to play with more restraint than their wild rockabilly records might suggest.

“The problem with kids trying to record today is they play too loud,” Van Eaton opines. “You have to play soft in the studio and let the engineer turn you up in the control room. Especially at 706 Union – that small studio. They didn’t have baffles between the instruments. You were out there on that open floor and it was very easy for the bass and especially the drums to bleed over into the vocal microphone. The piano wasn’t amplified and we didn’t have earphones, so our whole deal in there was if you couldn’t hear the piano you were too loud. We had to get down below the piano, especially with Jerry Lee.”

Production duties were split between Clement and Sun founder Sam Phillips. They both had different styles.

“You always wanted to please Sam,” Van Eaton remembers. “You could tell when you were doing it right. He’d get a big smile on his face. Jack Clement was more of a musician. He could tell you if you needed to change keys or modulate. Sam was more of a sound man. He could listen and he may not be able to tell you how to fix it if it was broke, but he’d come out and say, ‘Aw, I don’t like that, play something different.’ He couldn’t actually tell you what to play, but when you played it and he liked it, it was ‘Yeah, that’s it! That’s what I want!’”

Among the classic songs Van Eaton played on at Sun were Jerry Lee’s Breathless and High School Confidential, Roy Orbison’s Claudette and Devil Doll, Warren Smith’s Uranium Rock and Charlie Rich’s Lonely Weekends and Who Will The Next Fool Be.

Because Phillips threw all of Sun’s limited resources behind Jerry Lee, his biggest seller, many of the other artists only saw success when they moved on to other labels and a great many now-classic records went either unreleased or largely unheard until collector’s labels began unearthing the Sun archives in the 1970s.

By the beginning of the 1960s, Sun’s brief period of hit-making was over and Van Eaton moved on like many other musicians of the time, in his case to run a vending machine company and, later, to become an investment banker.

“I got married and wanted more for my family, so I had to find something else to do, because I wasn’t making enough money playing sessions,” he says. “But I never quit playing. Roland Janes and I had a band and played around Memphis for about five years in this one club, three nights a week.”

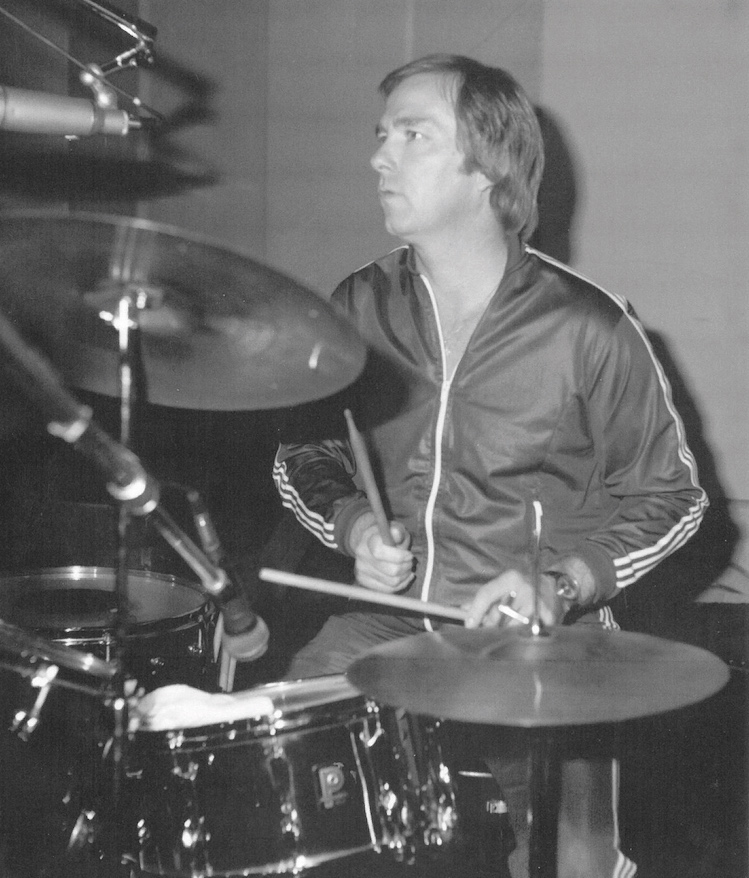

He later became involved in gospel music and in the early 80s returned to rock for some live dates with Jerry Lee. More recently, the now retired investment banker has been performing with former Sun star Hayden Thompson. The two will be appearing together at the Wildest Cats In Town this summer, when Van Eaton makes his first ever appearance in the UK.

Reflecting on the enduring interest in the records he made at Sun, the now 81-year-old Van Eaton says, “It’s hard to believe we’re still talking about it. It seems like every time you think you’ve heard all there is to hear about it, something new pops up. Last year they had the TV series. Now they’re getting ready to make a movie about Sam Phillips with Leonardo DiCaprio as Sam. There’s always something new to keep interest in Sun alive.”

All photos copyright Jimmy Van Eaton