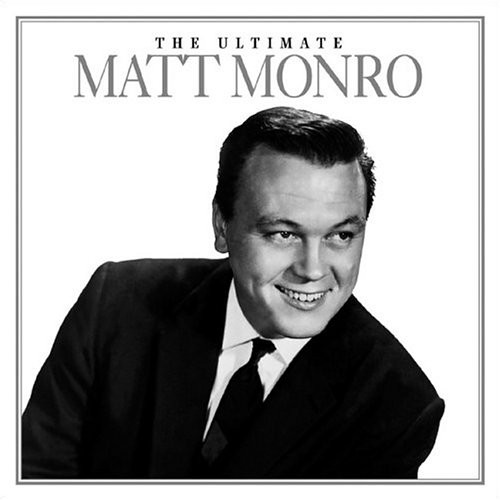

His was the velveteen voice behind three of the greatest movie songs of the 60s – From Russia With Love, Born Free and On Days Like These. Vintage Rock talks Matt Monro with his daughter Michele.

“If I had to choose three of the finest male vocalists in the singing business,” Frank Sinatra once said, “Matt Monro would be one of them. His pitch was right on the nose; his word enunciations letter-perfect; his understanding of a song thorough.”

As tributes go, certainly if you’re in the singing game, it doesn’t get any better than that. Sometimes known as ‘the singer’s singer’, and at other times as ‘the man with the golden voice’, Matt Monro was one of the biggest recording stars of the 1960s, a man who, in 1961, was named Billboard magazine’s Top International Act and who, in 1964, was the face of Britain in the Eurovision Song Contest. One of his most famous numbers, Born Free, even scooped an Oscar. As easy listening artists went in the 1960s, there were few more famous and more loved than Matt Monro.

Like Sinatra, Monro’s music and classy, perma-tuxedoed image were far removed from his humble, working-class beginnings. It’s not for nothing that his other nickname, the one he was rather less proud of, was ‘the singing bus driver’ on account of the rather humdrum job he had before becoming a global star. Even his name was a showbiz sham.

Before he was the suited and booted Matt Monro with the honeyed voice and suave demeanour he was plain Terry Parsons from Shoreditch, and from a family that, his daughter Michele tells us, were “very, very poor”. The moniker, incidentally, came from a combination of the first journalist to write about him, Matt White, and Munro Atwell, the father of the jazz pianist Winifred Atwell, who’d secured him his first recording gig.

“Dad was one of five children, and his father died when he was only three, so his mother struggled to clothe, feed and house five children,” Michele tells Vintage Rock. “They had no possessions as such. And dad went to, well, I lost count after five schools. It was a very displaced childhood.”

Born in 1930, Terry Parsons entered his teenage years while the Second World War raged. And like many kids who are surrounded by chaos and terror, he sought solace and escape through the transistor radio, where he’d soak up the pacifying voices of Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby and Perry Como. “He used to listen to Radio Luxembourg and the music he heard took him away from reality,” says Michele. “Well, you could dream, couldn’t you?”

December 2020 would have been Matt Monro’s 90th birthday, had he not been taken from us, far too young, at the age of 54 in 1985. Yet interest in the singer has never been higher. Only this year, his latest CD collection, Stranger In Paradise: The Lost New York Sessions, curated by Michele and remastered by her partner Richard Moore, went Top 10, while Michele regularly plays to packed out theatres – well, before social distancing rules made capacity-crowds a no-no – to talk about her late dad.

When Michele performs her talks, they’re usually peppered with weighty name drops, as Matt Monro brushed shoulders with pretty much everyone of note in the 1950s and 60s. Two of the most stellar names cited are Sir George Martin and Peter Sellers, both of whom, back in 1960, were key to Monro’s breakthrough success. Though he had gigged and recorded in the 50s, fame had somehow eluded Monro.

It was only when George Martin, then a couple of years away from buddying up with The Beatles, chose him for a gig on a Peter Sellers comedy album titled Songs For Swingin’ Sellers, that his luck began to change. Martin had written a Sinatra pastiche called You Keep Me Swingin’ for the Goons star, but when Sellers admitted he was unsure of how to sing it, Martin hired Monro to record a guide vocal.

Sellers, impressed by Monro’s performance, ditched the original idea and included Monro’s version of the song on the record instead. The only downside for the wannabe star was that the vocal was credited to ‘Fred Flange’ on the album.

Still, Parlophone – and Martin – knew Fred Flange’s real identity and swiftly signed the 30-year-old crooner. Within a few months, Matt Monro would have his first UK hit, the lush, swoonsome Portrait Of My Love. Produced by Martin, the record was the first of many that the two would collaborate on.

“They were such good friends,” Michele Monro tells Vintage Rock. “They had the same sense of humour. They would literally corpse on the floor in the studio and had this excellent rapport with each other. George respected dad’s talent, and likewise with dad. They were kind of in awe of each other’s abilities. I mean, George found dad before he found The Beatles and he recognised there was something special there. That relationship carried on throughout dad’s life.”

A string of hits followed Portrait Of My Love, culminating in the offer, in 1963, to record the theme song for the much-anticipated sequel to the James Bond film Dr. No. Unlike every Bond theme that came after, however, Monro’s vocals for From Russia With Love aren’t in the opening title sequence. Instead, he’s heard for the first time on a radio while Bond is smooching by a river, and then again during the end titles.

“I couldn’t believe that was all there was, I was terribly upset,” said Monro’s wife Mickie, in an interview before she died. “Matt loved the Bond films and was avidly watching the action. He seemed immersed in the movie, so I didn’t voice my upset but knew he must have felt disappointed himself. Then, right at the very end at the closing credits, his voice filled the cinema and in the space of seconds I went from feeling decidedly dejected to euphoric.”

From Russia With Love, along with another John Barry composition, the soaring Born Free, remain Monro’s most beloved, and certainly in his lifetime, requested tracks. Sometimes, however, signature songs can become millstones round the necks of the singers who sing them. But not to Monro, it appears.

“He never got tired of singing them,” says Michele. “He always said, ‘Those songs made me popular and if that’s what people want to hear, I’m happy to oblige’. It got difficult after a few years because the fans who came to see him wanted their favourites, so it was tricky to put new material in a show in case some of them went away disappointed. I mean, I released an album a few years ago and made the mistake of missing out On Days Like These [featured in The Italian Job]. The backlash I got!”

Though Monro’s song for 1964’s Eurovision Song Contest, I Love The Little Things, came second, it was onwards and upwards for the rest of the 60s. The gorgeous Walk Away (with lyrics from Don Black) went Top Five in 1964, while his strings-laden take on The Beatles’ Yesterday – he was the first person to cover the song – peaked at No.8 in 1965.

As Matt Monro’s career was on the up, apparently so was his home life. Though his first marriage had ended in divorce, he’d met music promoter Renate Schuller (known as Mickie) in the late 50s and they married in 1959, producing two children, daughter Michele and son Matt Jr.

“There was always music in the house,” remembers Michele of her childhood. “Dad would have friends round and they’d rehearse. He had hundreds of tapes sent to him every week from musicians. So they’d have several four- to five-hour sessions just listening to tracks, him and [arrangers] Colin Keyes and Johnnie Spence. And then if George Martin came over, if they were going into the studio, they would literally sit down and talk about how many musicians they should have, what the line-up should be, what the feel of the track should be, so that when they went in the studio, everybody would know their job already.”

Monro’s star wattage was so bright in the 1960s that, in 1969, he was even offered a job in a Hollywood movie. Satan’s Harvest isn’t a great film by any stretch, a ho-hum South Africa-set adventure co-starring Tippi Hedren, but its director, the former actor and stuntman George Montgomery, was such a fan of Monro’s that he gave him carte blanche on who he played in the movie.

“Dad went, ‘Thanks, but I can’t act,’ and George just said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about that’,” laughs Michelle. “So he sent dad the script and told him to pick any role he wanted, and so dad picked the role of this bush pilot, who only had one line in the whole movie – he figured that was a safe bet.

“But unbeknownst to him, George then rewrote the whole script so that dad’s character was in it throughout. He loved it, though. He loved filming in South Africa, and he loved the camaraderie on set because, as a singer, you’re alone out on stage, so it was a whole different ball game for him. He was very sad when the shoot came to an end.”

By the 1970s, however, Monro’s brand of smooth balladry was sadly going out of fashion and his last chart hit came in 1973 with a track called And You Smiled, which was essentially the theme to the ITV crime drama Van Der Valk (titled Eye Level in its instrumental form) with added lyrics.

The 1970s also brought two great tragedies. The deaths of his mother and then, soon after, of his friend and musical arranger Johnnie Spence at the age of just 43, devastated Monro and exacerbated his already excessive drinking.

“Johnny and dad were like brothers,” says Michele, “and Johnny dying, it just finished him. It was part of a long series of events that he wasn’t happy with in his life.”

Much has been made of Monro’s supposed alcoholism, but Michele maintains his drinking was, for the most part, heavy, as opposed to out of control.

“He didn’t drink in the morning, and he didn’t hide bottles,” she stresses. “I think it’s the difference between an alcoholic and a drunk.”

It didn’t help that Monro was born with infective hepatitis and was hospitalised for two years, a fact no one bothered to tell him later in life. Suffering jaundice and stomach pains in the late 70s, Monro went to the doctor only to be told his liver couldn’t process alcohol properly. “If he was in a town where there were several theatres and Dave Allen or Tommy Cooper were in a show up the road, those boys would get together afterwards and play cards all night. Drinking sessions could sometimes break out.”

The extent of Monro’s drinking was something Michele only discovered when she began researching her 2010 biography, Matt Monro: The Singer’s Singer. The family had been approached by various writers over the years, keen to tell the story of Britain’s Sinatra, but Michele says the angle was always the drinking. “That’s all they wanted to focus on,” she says, “but I thought, that doesn’t define the person.”

Not keen to have someone rifling through her dad’s letters and contracts (“It would have meant opening the house up to strangers and I didn’t fancy that,” she says), Michele decided to take the job on herself.

“I did say to my mum, ‘I’m not writing a fairytale, it has to be warts and all’. I interviewed over 200 people, and all his musical directors and asked, well what was he like, was he ever drunk, was he ever not able to perform properly? And I couldn’t get anything negative, they were all, no, it was never like that.”

Michele says her dad gave up drinking completely in 1980. After suffering a fit, he was told by a doctor, “You can either give up alcohol or you’re going to kill yourself.”

“He gave up overnight,” she says, proudly. “He never went to any AA meetings, never ever got tempted, even though we had a full bar in the house for his friends. If he was at the pub, he’d just have a tonic water.”

Sadly, the damage done to his liver caught up with him and, in late 1984, while performing in Australia, he was diagnosed with cancer. He was put on a waiting list for a transplant, but though a donor was found and an operation started, it was soon discovered that the cancer had spread.

While on his deathbed, Monro received a get-well telegram that read “From one boy singer to another”. It was signed ‘Frank Sinatra’. He died a day later. If, as Dean Martin famously said, “It’s Frank’s world, we just live in it”, it’s clear there was always a special place in it for Matt Monro.