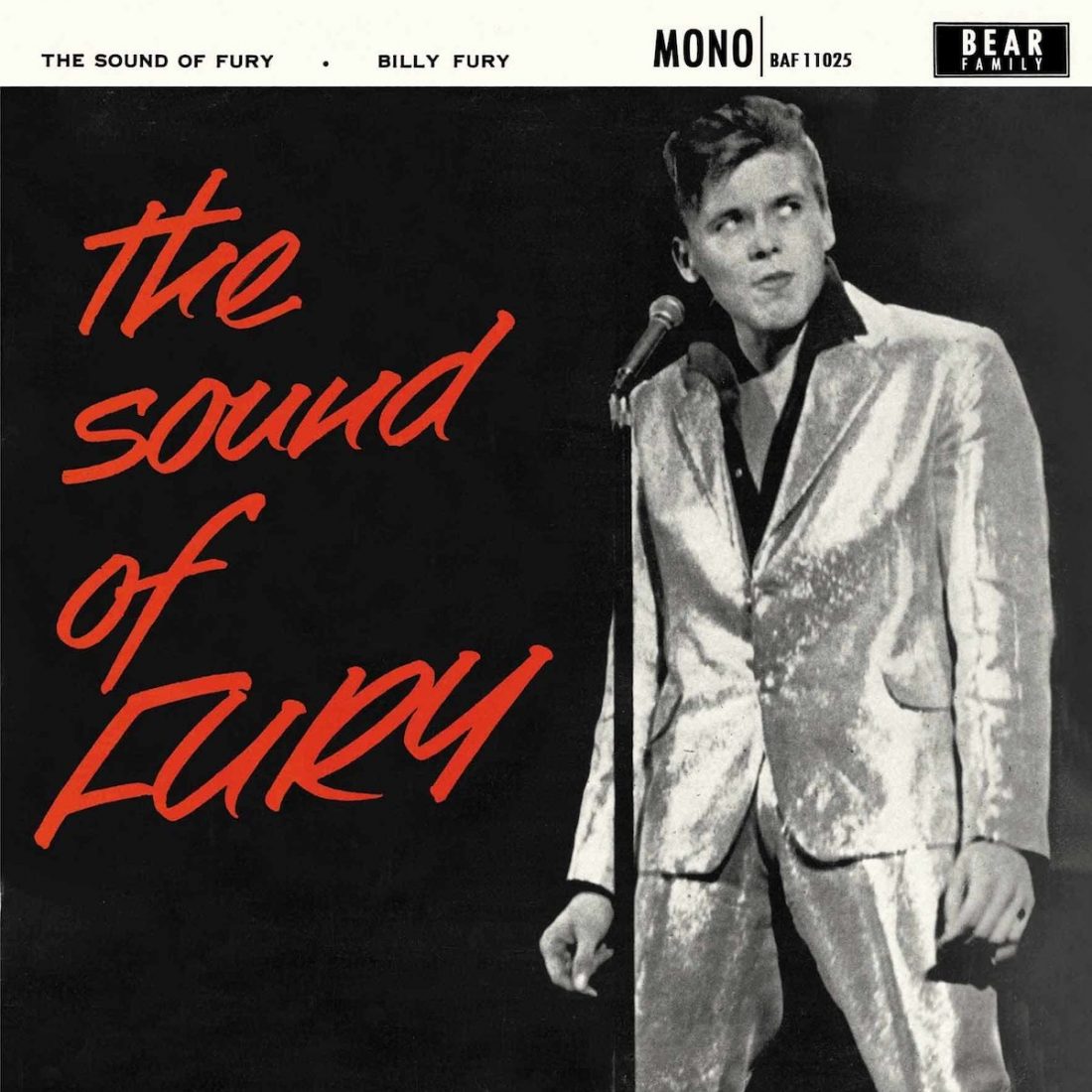

Not only was he, arguably, British pop’s first major singer-songwriter, but Billy Fury was also the creative force behind The Sound Of Fury. Alan Clayson chronicles its journey…

He racked up heftier commercial achievements after the 1960s, but to connoisseurs Billy Fury’s reputation will always rest on self-written The Sound Of Fury. Yet it was not a greatly appreciated disc when first released on Decca in June 1960. It didn’t make much of a dent in the album list, and its single, That’s Love, only just made the Top 20, a placing regarded by Billy’s investors as a setback.

So it was that Billy was to recall shortly before his death in 1983: “Decca got really heavy with me, and persuaded me I was going in the wrong direction, and slowly swayed me towards ballads.” This new approach meant no more Fury compositions were to be risked as A-sides, but he was to remain a hit parade contender until he bid farewell to the Top 40 forever in 1966. By then, Fury had reinvented himself as more of an ‘all round entertainer’.

OVERNIGHT SENSATION

Ronald Wycherley entered the world of work as a riveter. Yet he’d already conceived a fancy that he’d like to make his way as a songwriter, and, from listening hard to Hank Williams, Johnnie Ray and early Elvis, was forever tinkering on his acoustic six-string and jotting fragments of verse on scrap paper.

“As I don’t write music,” he was to elucidate, “I pick out chords on guitar and then transfer the basic tune onto a tape.” Shards of inspiration cut him when mooching to the corner shop.

Others jerked him from slumber. Dawn would seem a year away as the ghost of an opening verse, maybe a sketchy chorus too, would smoulder into form and engross him until daylight found him dozing over his instrument, surrounded by cigarette butts, smeared coffee cups and pages of scribbled lyrics and musical symbols peculiar to himself.

On days when little would come, he might position himself in front of the wardrobe mirror, and perform to thousands of ecstatic fans that only he could see.

Such a ritual of thwarted eroticism wasn’t entirely without justification, for Wycherley’s lop-sided grin, ‘common’ good looks, lavishly-whorled quiff and tight-trousered ‘cat’ clothes were already the spring of much discussion among the vicinity’s girls.

Moreover, when The Girl Can’t Help It was screened at Liverpool’s Scala cinema in 1957, Ronald, lost in wonder afterwards, had been tickled when someone remarked on his resemblance to Eddie Cochran, one of the US rock‘n’rollers who’d delivered a cameo performance in the movie.

Taking constructive action, Ronald recorded a guitar-and-voice acetate of one of his compositions, Love’s A-Callin’, plus four Presley items. This, plus a photograph of himself, landed on the desk of Larry Parnes, the country’s leading pop svengali. The principal stud in his stable was Marty Wilde, then on terms of fluctuating equality with Cliff Richard as the kingdom’s ‘answer’ to Elvis.

Parnes suggested that Wycherley present himself when the current round-Britain package tour, headlined by Marty, reached Birkenhead. That October 1958 evening in Wilde’s dressing room, Ronald, like a travelling salesman with a foot in the door, made a pitch with his wares.

Clearing his throat, he started chugging chords; a deep breath and into the first line of Margo, a lovelorn plea to a lass at work. As this and two further songs died, he blinked at his feet before glancing up with enquiring eyebrow.

Enthralled as much by Ronald’s crouched force, Larry gave him an immediate new name, ‘Billy Fury’, and squeezed him and his lone guitar into the show. The proverbial ‘overnight sensation’, Billy-Ronald was next dressed in gold lamé, and his metamorphosis from nobody to idol was set in motion.

He took to it like a duck to water – to the degree that a prudish adult Britain obliged him to moderate his sub-Elvis gyrations, though beneath it all, he was perceived by female fans as a little-boy-lost type.

The first A-sides, Maybe Tomorrow and Margo, were realised during regulated Musicians Union hours in Decca’s complex in Broadhurst Gardens, West Hampstead. There, he’d be subject to that sight-reading condescension that was the norm within that self-contained caste of middle-aged, middle-of-the-road musicians who were omnipresent in London studios throughout the 1950s.

After they’d listened to his demos, Fury, aware of the pound sign over every quaver, would run through the essentials of each before vanishing into the vocal isolation booth.

The two singles penetrated the Top 30 before 1959 was out, and Billy was to make regular appearances on Boy Meets Girls and Wham!, televised pop from the stencil of Oh Boy!, the more exciting ITV series, during which so swiftly did its atmospheric parade of Cliff, Marty and other domestic icons pass before the cameras that the screaming studio audience, urged on by producer Jack Good, scarcely had pause to draw breath.

As the decade turned, the inspired Jack was branching out into record production, and it was he, rather than Larry Parnes, who persuaded Decca to permit Billy to record his own creations as opposed to the customary play-it-safe US covers and ditties by jobbing tunesmiths. “He had that schoolmaster effect over you,” confessed Dave of his producer Norrie Paramor. “So many of us were not allowed to do what we really wanted to do.”

Well into the 1960s, a critical prejudice of most record label artist-and-repertoire managers – including Paramor and Decca’s Dick Rowe – was that the last thing anyone, from a teenager in a ballroom to the head of the BBC Light Programme, wanted to hear was a home-made song.

Even exceptions like Cliff Richard’s Move It and Shakin’ All Over from Johnny Kidd began as flip-sides. It was usually presumed that, when an artiste boasted of recording his own material, his handlers had hired some ‘professional’ songwriter to come up with numbers.

TRIAL AND ERROR

With Billy Fury’s chart breakthrough not yet consolidated, it was, therefore, extremely unorthodox, even verging on lunacy, for Decca and Parnes to agree to an album consisting entirely of originals, albeit a monophonic ten-inch 33 rpm long-player – somewhere between the increasingly more common twelve-incher and the EP (extended play).

Into the bargain, Jack Good decided that Billy was to be troubled as little as possible by that dictate that British pop couldn’t be done in any other way or with any others than those bound by the rigidity of union officials.

Furthermore, if approaching his 30s, Jack wasn’t self-deprecating about his knowledge and love of pop when Billy arrived at his flat, armed with demos and nebulous ideas. “I loved rockabilly,” outlined Billy in one of his final interviews, “and all the songs I was writing then were basically around that kind of musical theme.”

Shortly afterwards, Good, Fury and a backing ensemble spent 8 January 1960 in Studio Three at West Hampstead focusing on Turn My Back On You, notable for the ‘flutter echo’ on the lead vocal, a combination of console manipulation and Billy’s own emulation of what he’d heard on discs in the rockabilly genre, which he’d now impregnated with an inbred originality, most insidiously via an approach that was more subtle than the typical hep-cat exultations about lust, violence, clothes and doin’ the Ooby Dooby with all o’ your might.

Instead, Billy addressed the joys and desperations of boy-girl love. “I get an idea when I’m depressed,” he’d explain, “usually because one of my girls has let me down.” Undoubtedly, Billy’s heartbreak was reflected in downbeat Since You’ve Been Gone, Phone Call, You Don’t Know and remorseful Alright, Goodbye, all tailored to suit his ‘wounded’ baritone.

With the less submissive Turn My Back On You in the can, the late Hal Carter, attendant to Fury’s day-to-day requirements, would remember that, “Jack was taken by the rockabilly thing too. Well, no-one did it over here like that, and he couldn’t wait to do more.”

Thus a second studio date was booked for the afternoon of Thursday 14 April 1960 at Studio 3 with fixed personnel, most conspicuously electric guitarist Joe Brown who, like Billy, was involved then in the lengthy twice-nightly ‘Fast-Moving Anglo-American Beat Show’, starring Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent, which had begun in January.

Joe had backed Billy on Boy Meets Girls, with renderings of Turn My Back On You and Presley’s Baby Let’s Play House on the same edition the most reliable signposts to what was to be released two months after Brown served as Scotty Moore to Fury’s Elvis at the second Studio Three session where each clangorous solo might take off amid yells of encouragement from others present.

Apart from Good, chief among these was 30-year-old pianist Reg Guest, who’d also been to the fore during a trial-and-error rehearsal in a nearby hall, notating what few dots were required as Billy dah-dah-dah-ed.

Better known now for his orchestral scorings for The Walker Brothers, Reg had been musical director for Good’s Six-Five Special, Oh Boy!’s more pious predecessor. As well as issuing records of his own – markedly, 1962’s Winklepicker Stomp as Earl Guest – Reg had worked too with both Eddie Cochran and Little Richard.

Crucially, if his heart was in jazz, he had a feel for the ‘slip note’ style – the resolving of deliberate dischords – of Floyd ‘Mr Piano’ Kramer, a virtuoso exponent of the ‘Nashville Sound’, who’d been on all manner of Presley recordings since Heartbreak Hotel, employing delicacy or force, as required.

If Reg was its Kramer, Joe its Moore– and drummer Andy White its DJ Fontana – The Sound Of Fury’s Jordanaires were The Four Jays, whose precise identity is blurred. Hal Carter, a fellow Scouser who, prior to entering the Larry Parnes orbit, had promoted regional dances and fronted a city skiffle combo said, “I can’t remember who The Four Jays were.”

But whoever they were, the quartet layered a smooth and cleanly executed chorale onto the grippingly slipshod passion of an instrumental thrust that players earning their tea break with infallibly polished nonchalance couldn’t have accomplished. For all their casually-strewn errors, the team on what became The Sound Of Fury kept pace as Billy shifted gear with the composure of a Formula One racer (as exemplified most obviously by the tempo change in Since You’ve Been Gone).

It amounted to the phonographic equivalent of bottling lightning: youthful adrenalin pumped onto a spool of tape with thrilling margin of error and the exhilaration of the impromptu being prized infinitely more than mere technical accuracy.

“When it came down to it,” concluded Good, “We had to accept stuff that sometimes you’d have liked to have improved on, but it did have spontaneity and simplicity. Billy’s voice, we made sure was always there, not smudged over loud backing. The soul of Billy Fury is in that record, and I’m very proud of that and I think Billy was too’.

For more on Billy Fury click here

- Read more: The voices of neo-rockabilly