Songwriting for Elvis on the screen was often a rollercoaster affair, full of highs and lows, hits and misses. Vintage Rock looks at the turbulent world of creating his hit movie material… By Julie Burns

Elvis’ move from Sun Records to the bright lights of RCA signalled a major change in his material. It meant that Hill & Range were now the major publishers on hand to source his songs. When he got to Hollywood, they shaped his movie music. At the start of his film career in the 50s, there were plenty of highlights – screen gems such as King Creole, Trouble, and Jailhouse Rock – from the cream of songwriters such as Leiber & Stoller, Pomus & Shuman, Otis Blackwell, and Ben Weisman. Many had cut their creative teeth as Broadway’s famed Brill Building songwriting teams, viewed as the epicentre of the American music industry before the 60s singer-songwriter revolution.

Another benefit of Elvis joining Hill & Range was special access to the artist catalogue belonging to its owners, the Aberbach brothers. It was a catalogue that included the go-ahead gospel-pop of Ray Charles; Elvis did well to cover What’d I Say in the classic Viva Las Vegas.

The Aberbachs’ younger cousin, Freddy Bienstock, was assigned to find promising songs for the stable’s latest, and greatest, star. As Elvis’ movies became more prolific (three a year, during the mid 60s), Freddy’s song sourcing operation hit overdrive, with teams involving up to 70 writers enlisted to help. It was a complex process, entailing unique publishing arrangements: two companies, Elvis Presley Music and Gladys Music – 50/50 owned by Elvis and the Aberbachs – put the focus purely on publishing Elvis’ songs, and getting the artist a credit where possible.

Across his movie output, Elvis sang a diverse range of material, a wild mix of hits and misses. Although Elvis was technically free to select his own songs, his manager Colonel Parker indirectly helped determine content by ensuring that new material went strictly through Hill & Range. This directed Elvis to what the publishers wanted him to hear, restricting any real choice of movie material he wished to sing. The upshot, for Elvis, was that this system netted him an additional third of songwriters’ royalties.

In commercial terms, the Colonel’s set-up, initially at least, proved a resounding success. Post-army, Elvis’ record sales were notably higher across soundtrack songs than for critically acclaimed RCA albums: G.I. Blues out-performed Elvis Is Back!, for instance. As an artist, however, for Elvis the downside ultimately meant being trapped in a cycle of movies accompanied by increasingly mundane songs.

It was difficult from the songwriters’ perspective too, as it was in effect about them accepting a rollercoaster ride on royalties – great if work was on some peak project like Blue Hawaii with two million sales in a year, dire when Presley’s soundtrack sales plummeted, as in its spiritual sequel, Paradise, Hawaiian Style. Elvis songwriting was a stressful, competitive field: Hill & Range commissioned teams of favoured partners to compete and create soundtrack numbers to order.

Up to 300 demos per movie would first be submitted, then whittled down to a requisite hit-list. On no account could Presley be approached directly, as Leiber and Stoller soon found to their cost. As Mike Stoller later stated: “When Elvis loved a song, he wanted to record it. Tom Parker and the Aberbachs’ greatest fear was that Elvis might insist on recording a song that their publishing company didn’t own.”

In interview, Freddy Bienstock of Hill & Range candidly explained the creative process: “Once we started on the MGM contract, with four pictures a year, it was like a factory… I would mark these scenes where a song could be done without being absolutely ridiculous, and then I would give those scripts to seven or eight songwriting teams. I’d wind up with four or five songs for each spot, and then I would take them to Elvis and he would choose which ones to do. But there was no way to have better music, because from the moment one picture was finished, we would have to get started on the next one.”

Dashed off by writers at breakneck speed, the song quota had to fit the hectic movie production deadlines, as well as constraining scripts and scenes. Songwriters were so pushed that in 1961 Elvis recorded almost 50 songs. Furthermore, anyone having an exclusive arrangement with a different publisher, was automatically barred from having an original track recorded by Presley. These boundaries were made worse by what the songwriters dubbed the ‘Elvis tax’ (the singer receiving a third more royalties).

Not surprisingly, it began to affect the quality, and quantity, of material submitted from top-flight songwriters. As competition increased, rewards for labour were uncertain. Many songs were unused. The songwriters’ potential, as well as Elvis’, did not always fit the scripts. It all came to a head in 1965 when for the first time, sales for one of the singer’s soundtracks plunged below 250,000 copies. Paradise, Hawaiian Style hit a new low – and yet its content came from the prestige trio Bill Giant, Bernie Baum and Florence Kaye.

With the movie machine set in relentless mode, and demand for new tracks voracious, song-handler Bienstock was finding the requisite quality material harder to come by. Thanks to the rise of The Beatles, along with independent singer-songwriters like Bob Dylan, times were clearly changing. As for Elvis, it was no secret he was close to artistic implosion. By now, he had suffered the indignity of singing Ito Eats, Yoga Is As Yoga Does, Old MacDonald and Queen Wahine’s Papaya.

According to Elvis Films FAQ author Paul Simpson: “Elvis advertised his disgust, nicknaming Bienstock ‘Freddy the freeloader’. On 15 January 1968, in Studio B Nashville, after cutting Stay Away, the Tepper/Bennett reworking… for Stay Away, Joe, Elvis finally rebelled… Presley shouted, ‘Doesn’t anyone have some goddam material worth recording?’ Jerry Reed, who was playing guitar on that session, jumped in with U.S. Male… After the recording, Bienstock and Elvis’s friend Lamar Fike, who was working for Hill & Range by then, pinned Reed to the wall. The singer/songwriter refused to give up any of his rights, and was saved when Elvis strolled past, saying pointedly: ‘Great tune, man. We need more of that around here.’”

Towards the end of his 60s movie era, Presley had an epiphany. With the realisation that Hill & Range were less able to control his live material, on that side, at least, he could explore other options. With free reign on his own set-list, it culminated in his glorious cutting loose on NBC TV’s ’68 Comeback Special. Never mind the movies, Elvis’ musical mojo was back. “I’m never going to sing another song I don’t believe in. I’m never going to make another picture I don’t believe in,” he famously said. A year later, it was goodbye to the silver screen, and hello to a future performing live in Vegas.

It’s interesting to look back to see how Elvis’ soundtracks developed. In 1956, Love Me Tender – his first film’s title track, adapted by musical director Ken Darby from the 1861 classical melody Aura Lea – though only released on EP, was a hit. The following film, Loving You, spawned Elvis’ first soundtrack album and set a format featuring compositions from several of Elvis’ mainstay writers. Of these, the following dream teams left the most lasting impression…

THE LEGENDARY LEIBER & STOLLER

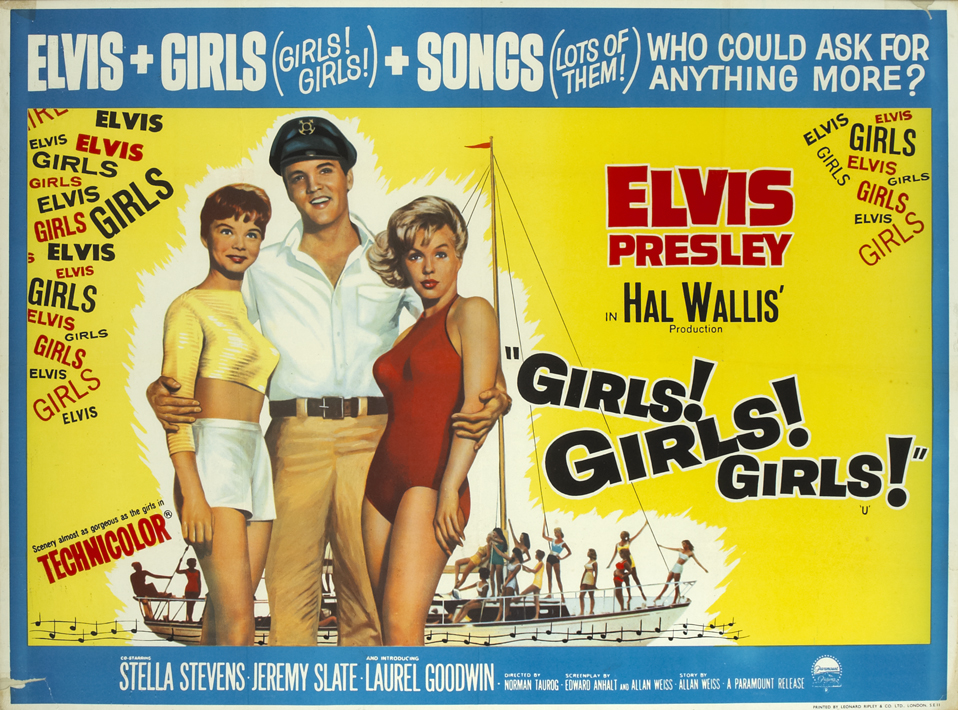

From the early 50s onwards, the dynamic duo wrote for a roll call of groundbreaking rock and roll artists. Their rollicking R&B sizzler for Big Mama Thornton, Hound Dog, became a smash hit for Elvis in ’56. The three first met when Elvis was recording four of their tracks for Jailhouse Rock. Gelling with the star from the off, Lieber and Stoller acted as co-producers for the session, before being made staff producers by RCA. More sterling work with the King came in ’58, on King Creole. The pair were impressed by his musical knowledge and ability; he was a natural fit for their hip and bluesy, lively approach. Their growing closeness as colleagues and friends of Elvis was something the Colonel didn’t like. In his eyes, they had made big mistakes, directly offering Elvis material like the song Don’t; and, the last straw, suggesting a cool film project for Elvis with Elia Kazan, called Walk On The Wild Side. For Presley’s post-army movie G.I. Blues, they submitted two songs: Dog Face and Tulsa’s Blues. Suddenly, they didn’t make the final cut. Faced with further suffocating contractual conditions, the duo felt forced to quit. They never worked closely with Elvis again, despite the inclusion of their title track for 1962’s Girls! Girls! Girls!, plus Bossa Nova Baby in Fun In Acapulco, and Little Egypt in Roustabout. They remained glittering writers, and were inducted into multiple Halls of Fame.

POPULAR POMUS & SHUMAN

Despite his childhood polio, Doc Pomus went on to become a successful singer. In the mid-50s, as lyricist, he partnered his long-term pianist Mort Shuman. The two joined Hill & Range while Elvis was in the army. Wary of any songwriters interfering with business, Parker ensured that they did not, in the main, get a chance to meet ‘his boy’ and feed him any ideas. Creators of some real crackers including His Latest Flame, Little Sister and Surrender, to film tracks such as Viva Las Vegas, the same film’s smoky late night I Need Somebody To Lean On, and G.I. Blues’ Doin’ The Best I Can, the duo would never get to meet the star who brought their songs to life. Ironically, the two broke up in 1965, after nine years of writing together, when Shuman left to write for ‘French Elvis’ Johnny Halliday. Sadly, following a treacherous fall, Pomus became consigned to a wheelchair. The once great writing team would fade away with the disappointing Double Trouble title track. Pomus was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

THE BRILLIANCE OF BEN WEISMAN

Perhaps the most resilient and prolific of all of Elvis’ songsmiths was Ben Weisman, with a credit on 57 mostly film-related tracks. A Tin Pan Alley musical prodigy and trained concert pianist, he started out writing for Dean Martin. Weisman’s first work with Elvis lay with earlier album track First In Line, before penning screen classics such as Crawfish, Got A Lot Of Livin’ To Do and Don’t Leave Me Now. Viewed as ultra-dedicated and non-complaining, uniquely, he was granted access to Elvis, who nicknamed him ‘The Mad Professor’ for his studious demeanour and frequent studio presence. Able to appreciate the singer’s cross-genre talent, Weisman variously attempted to write in the feel of country, rock and blues. Remarkably versatile, his co-writing collaborations include Wooden Heart, Rock-A-Hula Baby, Change Of Habit, Happy Ending, and Pocketful Of Rainbows. His main black mark was the almighty clanger Dominic (aka ‘the bull song’) in Stay Away, Joe, chosen without the King’s consent. In Elvis’ final film, Change Of Habit, Weisman credits still featured prominently. Before his death in 2009, he said: “What do you do when you’re asked to write a song called A Dog’s Life? Write it. Because if you don’t, someone else will.”

THE TALENT OF TEPPER & BENNETT

This unstoppable pair once penned five movie songs in a single afternoon. The first number that the diligent duo composed for Elvis was Lonesome Cowboy, for Loving You. In total, Tepper and Bennett wrote 42 songs for him, 37 for the movies, including most of the material for the G.I. Blues and Blue Hawaii soundtracks. Roy Bennett recalled the relief of having an Elvis song accepted: “After the movie was in the can, Freddy Bienstock would call in the writers, and tell them how they made out. Having the title song was the supreme achievement.” They were awarded with the title tracks for G.I. Blues and Stay Away, Joe. Of over 300 songs they crafted, 15 were actually hits for Cliff Richard, including his 1961 smash The Young Ones. Back to their main client, the Brill Building boys contributed, amongst others, New Orleans (King Creole), Angel (Follow That Dream), All That I Am (Spinout), A House That Has Everything (Clambake), and the sweet Elvis/Ann-Margret duet The Lady Loves Me (Viva Las Vegas). In 2002, in a ceremony in Memphis, they were honoured by Lisa Marie Presley for their contribution to her father’s success.

THE DRAMA BALLADS OF DON ROBERTSON

On writing for Elvis, the romantically inspired songwriter said: “It was tough to come up with really great songs to fit all those movie script situations. And it was kind of sad to me to see Elvis involved in less than top quality, first-rate things. However, all of our staff writers were just spitting out songs to fit specific situations and to help those movie plots along.” He added, “When Elvis sang one of my songs, I never had the feeling that he was throwing them away like artists do…” Elvis first recorded one of Robertson’s songs – I’m Counting On You – in 1956, for his first RCA album. Though not as instantly known as Leiber and Stoller, Robertson’s 60s output for Elvis, with his beautiful ballads, was considerable and consistent in quality. So much so that by the start of the 21st century, his stellar songs reportedly accounted for 500 million sales worldwide. Catalogue highlights include I Met Her Today, Starting Today, There’s Always Me, and the film tracks No More, Love Me Tonight, They Remind Me Too Much Of You, I’m Falling in Love Tonight, and Marguerita, to name just some.

THE EVERGREEN GEMS OF BOB JOHNSTON & JOY BYERS

In 1964, Elvis only recorded three non-soundtrack songs. Yet when he was given free reign to use a quality composition, he sang like a man unleashed. The Joy Byers and Charles E. Daniels’ ballad It Hurts Me, from that same year – and later showcased in the ’68 Comeback Special – was an Elvis favourite, often cited by critics as a great song and performance. Intriguingly, record producer and songwriter Bob Johnston later claimed to write material under his wife’s name, Joy Byers. Johnston co-wrote 15 other songs for the King, including such upbeat fan favourites as Hard Knocks, Let Yourself Go and Stop, Look And Listen.

THE TOP TRIO OF GIANT, BAUM & KAYE

A strong presence on much of Presley’s swinging 60s fare, the trio dominated across soundtracks for Kissin’ Cousins and Roustabout, the latter a best-selling album and Billboard No.1. Yet by 1965, for the first time, sales tanked for one of Elvis’ screen LPs. The culprit was Paradise, Hawaiian Style, a mundane example of the parnership’s output, with the lowest point being Queen Wahine’s Papaya. The fact that they were writing sterling songs for other artists at the time suggests that the movie conveyor belt undermined their efforts for Elvis. In one overworked two-year period, the trio wrote a total of 42 songs for Elvis, 22 as soundtrack numbers. Happily, they returned to form extensively across Frankie And Johnny, and with numbers like Spinout’s Beach Shack, and Live A Little, Love A Little’s acid rock pastiche, Edge Of Reality. Also worthy of a mention is their punchy, could-have-been-great-for-a-movie number Power Of My Love, which at least found a prestige place album-wise, after Presley’s famed Memphis Sessions.

THE BRIGHT SPOT OF BILLY STRANGE AND MAC DAVIS

An in-demand, multi-talented musician and a member of LA’s elite session team, The Wrecking Crew, Billy Strange began work with Elvis in 1962 as a guitarist on the soundtrack for It Happened At The World’s Fair. Viva Las Vegas and Roustabout soon ensued. After subsequent producing of Elvis soundtrack sessions, Strange was elevated to musical director on Live A Little, Love A Little and The Trouble With Girls. Later in the movie doldrums decade, thanks to soul-funk savvy Strange and Mac Davis of In the Ghetto fame, Elvis ended on a better note. They co-wrote a couple of barnstormers: Clean Up Your Own Backyard and A Little Less Conversation, so good it triggered the JXL smash remix of 2002. Of Elvis’ movie records, Strange said: “He had more talent than he was ever able to show.”

BEST OF THE REST

Other writers managed fewer songs but produced screen gems nevertheless. Notable examples are (Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear (Kal Mann and Bernie Lowe) and (Let’s Have A) Party (Jessie Mae Robinson), both from Loving You; King Creole’s Mean Woman Blues and the gold-selling Billboard No.1 Hard Headed Woman (both Claude Demetrius), and Dixieland Rock (Demetrius with Fred Wise); the eponymous Wild In The Country by the accomplished Peretti, Creatore and Weiss (the team that was also behind the timeless classic Can’t Help Falling In Love); plus the stompers Put The Blame On Me (Fred Wise, Kay Twomey and Norman Blagman) from Tickle Me; and Double Trouble’s dynamic Long Legged Girl (With The Short Dress On) penned by J. Leslie McFarland and Winfield Scott.