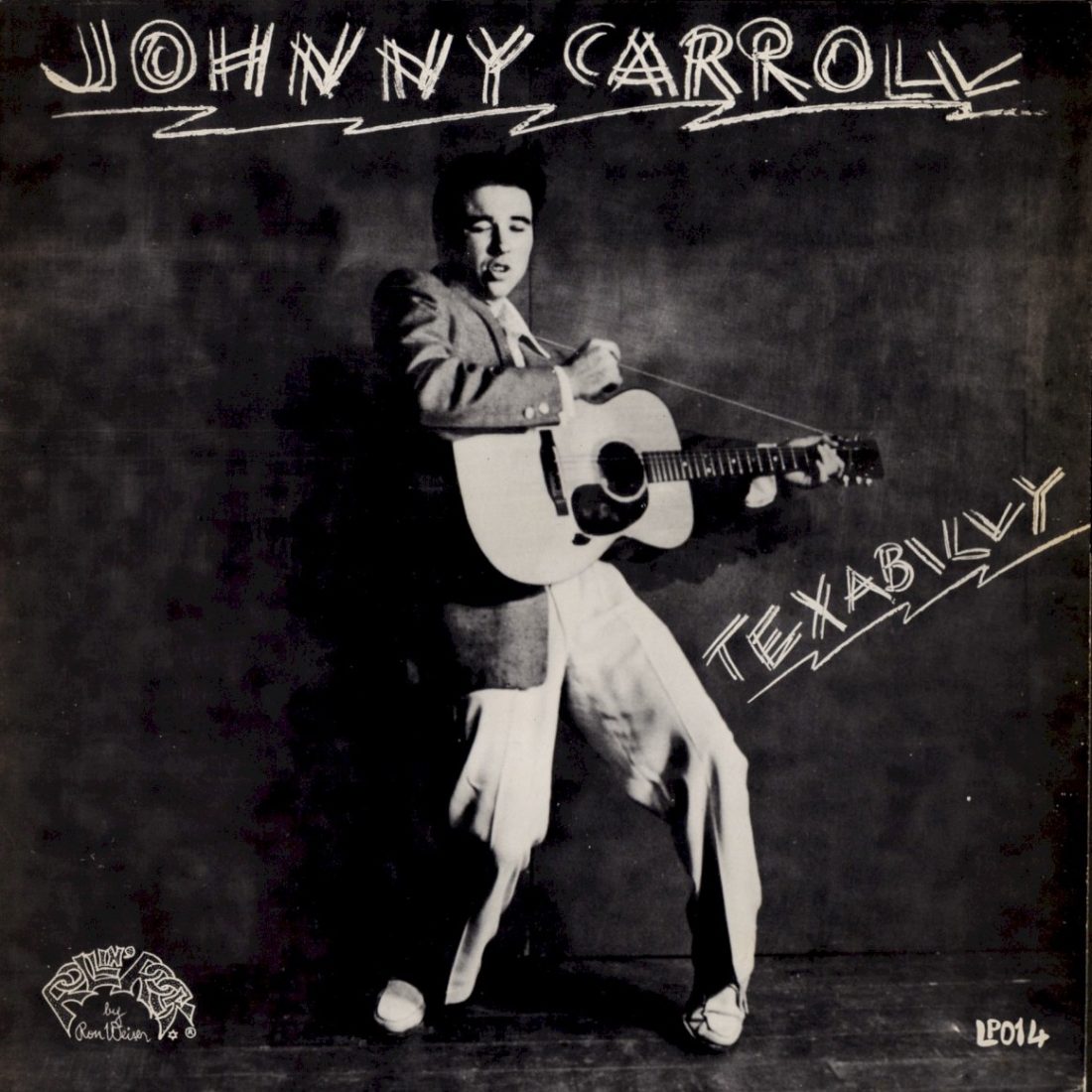

Johnny Carroll was one of many rockabilly pioneers who never made it to the big time. Joining Ronny Weiser’s Rollin’ Rock label in the 70s raised his profile among hardcore fans and enabled him to cut his first album… By Jack Watkins

If Memphis, Tennessee, was the crucible of rockabilly, Texas added many stellar names to the mix. Apart from Roy Orbison, Buddy Holly and the pop-inclined Buddy Knox, the likes of Mac Curtis, “Groovey” Joe Poovey, Huelyn Duvall, Ray Sharpe, Gene Summers, Sonny Fisher, Bob Luman and the New-York born, Texas-domiciled Ray Campi were revered figures from the Lone Star State. Then there was Johnny Carroll, whose 1978 album Texabilly emphasised his origins.

Carroll’s profile hadn’t extended much beyond the Southern states in the 50s. Although he had singles released by Decca, Sun’s subsidiary label Phillips International and Warner Bros, only the excellent Bandstand Doll, recorded in Dallas in 1958, charted regionally. While it wasn’t a rocker, it was the nearest he came to a hit. Carroll stopped recording for years from 1962, and 16 years later Texabilly was his solo debut.

Even so, thanks largely to the appearance of some early singles on the MCA Rare Rockabilly albums in the mid-70s, Carroll was a big name for hardcore rockabillies. As Ronny Weiser described it on the Texabilly sleeve, Carroll was one of the original wildcats, an incendiary rocker whose searing early recordings were as over-the-top as it got in terms of frantic, sub-Elvis styled rockabilly vocalising.

At the age of 18, Carroll had been one of the first of the new-generation hepcats to get picked up by a major label, Decca, in 1956. Born in Cleburne, Texas, his real surname was Carrell, but it was spelt wrong on the label of his first Decca release, so he stuck with it. Carroll formed his first band, the Texas Moonlighters, at high school. They were good enough to open for country star Ferlin Husky in Fort Worth in 1955, and play the Big D Jamboree in Dallas and the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport.

Local hustler Jack Goldman spotted Carroll’s scowling potential and, bringing him to the attention of Decca, took the band to Dallas. Now renamed the Hot Rocks, they cut some demos. Of those, You Two-Timed Me One Time Too Often, which borrowed elements of Presley’s I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone and took it at a faster tempo, was by far the best.

The demos landed Carroll, minus his mates, a session in Nashville, backed by some of the town’s most dependable sidemen such as lead guitarist Grady Martin, Harold Bradley on rhythm, bassist Bob Moore and drummer Farris Coursey. They supplied the perfect backdrop for Carroll’s performances. On Crazy Crazy Lovin’ and Hot Rock, he delivered two great yelping, hiccupping performances in the early rockabilly style.

Carroll was not in Presley’s class, but at the same session he did a superb rockin’ version of Corrine, Corrina, recently revived by Joe Turner. His Rock ‘n’ Roll Ruby was especially notable, given he was only given Johnny Cash’s demo of the song at the session. Modestly, Carroll later said he felt that his singing on it “might have been a little too frantic”, admitting he preferred Warren Smith’s version. But, overall, the work here stood comparison with what was being released by Sun at the time.

Despite Goldman’s attempts to promote Carroll by bankrolling a cheap rock movie, 1957’s Rock, Baby, Rock It, which Carroll detested, the cards never fell for the artist, regardless of his distinctive looks and authenticity. Astonishingly, although Sam Phillips bought four Carroll songs in 1957, he never released the best of them, the fantastic Rock, Baby, Rock It – not in fact a song from the movie.

By the early 70s, the Italian-born Weiser had arrived in Los Angeles, launching Rollin’ Rock Records and setting about luring old-school rockers into his home studio. Carroll had been a target for several years and he’d worked with him briefly in 1974 when they collaborated on a Gene Vincent tribute song Black Leather Rebel (see boxout). Released as a single in the UK, it did no harm to Carroll’s growing underground reputation.

In 1978, Carroll, who’d started playing gigs again, called Weiser and growled down the wire, “I’m ready to cut an album. Pick me up at the airport.” Weiser called Ray Campi, the first of the 50s rockabillies he’d recorded after setting up Rollin’ Rock, to provide backing. Weiser claimed the first session amounted to nine hours of straight recording, “with only 15 minutes off to eat! My God, what an ordeal.” This was followed by a second day “marathon” that involved 20 hours of recording, “really exhausting, but sure worth the trouble!”

Inevitably, given Weiser’s limited resources, the production was sparse, Carroll providing all the guitar work. Campi, a multi-instrumentalist who’d only taken up the string bass on Weiser’s urgings because he felt it made for a more authentic rockabilly sound, plucked and slapped away energetically. Steve Roosh, a friend of Weiser’s who had written songs for Campi, played piano and drums.

Carroll’s voice also enforced certain restrictions. Still only 40, he sounded older, the boyish tones of the 50s replaced by a low-key growl. He had, though, become a decent guitarist, tutored by Scotty Moore when they toured together and Bill Black, after their split from Elvis.

Texabilly opens with A Little Bit Of Your Time, essentially built around a call and response between Carroll’s voice and the bass strings of his guitar. Is It Easy To Be Easy is a country song about a ‘friendly’ lady, delivered with a rockabilly kick, Campi’s clicking bass to the fore. Singing “I remember her and the bar/ but I don’t recall the door,” Carroll’s on classic honky-tonk ground, the song suiting his now scratchy tones perfectly.

Judy Judy Judy is not the Johnny Tillotson song of the same name, but a driving blues number, penned by Carroll and dedicated to ex-model Judy Lindsay, his singing partner at his live shows. Writing on the album cover, Carroll dedicated the entire LP to her. Without Lindsay, he said, “I would not have even gotten back to singing.” The track gave him the chance to dash off a few rudimentary blues licks, too.

Steve Roosh wrote the up-tempo rocker Does Your Mama Know, and supplies some lively piano, with Carroll adopting a curiously strangulated tone to deliver rock’n’roll clichés such as “Ah, you’re lookin’ like a woman/ You know you’re still goin’ to school.” It’s a good number, although it might have benefitted from some restrained use of tape echo.

The old folk-blues standard My Bucket’s Got A Hole In It gets a classic rockabilly treatment well within Carroll’s comfort zone, and Campi’s slapped bass is again excellent. Sixteen Tons Rockabilly, meanwhile, is a reworking of what had by the 70s become another standard. Carroll was never going to match Frankie Laine or Tennessee Ernie Ford for vocal fireworks – both had hits with the Merle Travis song in the 50s. Instead, the focus was on the moody, restless feeling created by his guitar.

The second side kicks off with the rocker Who’s To Say which, thanks to its memorable opening riff, should have opened the album. People In Texas Like To Dance is a light-hearted country stomper that plays on Carroll’s Texas dancehall origins. Observations such as “People in Texas love to dance/ Don’t play them no freaky beat ’cos they won’t get off their pants,” and if “If you can’t play rockabilly you ain’t got no chance” probably came from experience.

The abbreviated title of Two Timin’ disguises the fact it’s none other than a revival of Carroll’s superb demo song from 1955, You Two-Timed Me One Time Too Often, now with a slightly muddy echo sound. Whatcha Gonna Do, the album’s longest track, might have been inspired by the basic lyrical premise of Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters’ zippy mid-50s R&B classic of the same name, while Why Don’t You Quit That Teasing is the album’s funkiest number.

Lonesome Boy had always been one of Gene Vincent’s most underrated, untypically introspective songs, kept in the can for five years after he recorded it in 1958, until Capitol put it on his The Crazy Beat Of Gene Vincent in 1963. Now Carroll revived it, perhaps in memory of his old friend, who’d died seven years before (see boxout). It was a fitting choice, Carroll, who’d often deployed some of Vincent’s vocal mannerisms, sounding like an older version of the Screaming End.

Although the front cover of Texabilly portrays Carroll in his hip-swinging, pouting pomp, a photo on the back has him smiling in bearded middle age. Weiser recalled that, while Carroll in his day was a “savage wild cat”, the new album showed that he “hadn’t yet been completely domesticated”.

A defiantly quirky release, Texabilly was a reminder that the old school, when given their chance, could still be a formidable creative force in the studio.