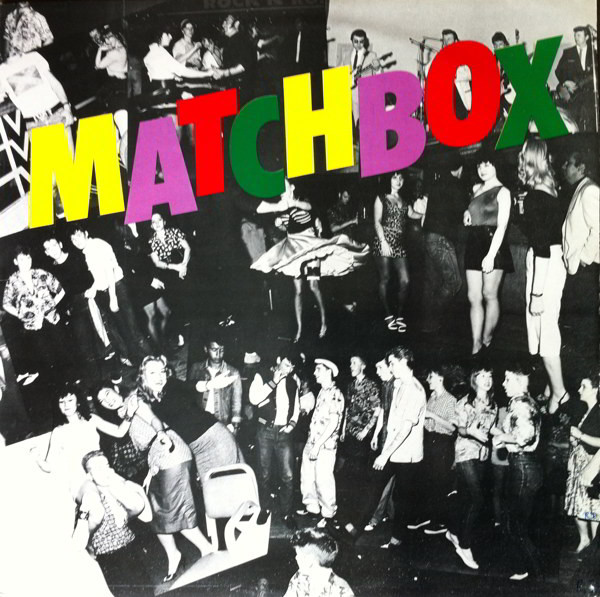

Matchbox’s eponymous third album was the first LP from the so-called rockabilly revival to penetrate the UK charts. This landmark record was a well-deserved breakthrough for a band who had long been stalwarts of the scene… By Jack Watkins

As Rockabilly Rebel was the first authentic UK pop single hit of the rockabilly revival, it seems right that the song starts with a metallic guitar sound not a million miles from the rumbling of a motorbike about to scorch the Tarmac. With one short riff, a whole musical movement sparked into life. Except it wasn’t that simple. Rockabilly Rebel may have become one of the commercial anthems of the genre, with the LP Matchbox, released not long after, enjoying parallel breakthrough success on the album charts, but it had been a while coming.

Throughout the 1970s, the spirit of the 50s and rock’n’roll was never far away in music and movies, and even in some mainstream fashion. But while by the late-70s, doo-wop outfits such as Darts (Come Back My Love, Duke Of Earl) and Rocky Sharpe And The Replays (Rama Lama Ding Dong) had found chart success, following on from Showaddywaddy, hardcore fans had their own underground scene. Matchbox had been staunch members of it since their formation in 1971, building a strong Ted following, along with bands including Shakin’ Stevens And The Sunsets, Crazy Cavan ‘n’ The Rhythm Rockers, The Wild Angels, The Riot Rockers and The Flying Saucers.

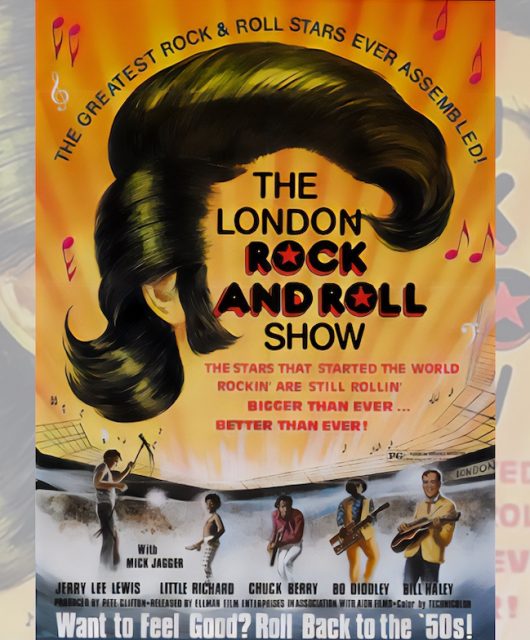

By 1979, Matchbox were also massively experienced, having backed or supported stellar visiting American acts such as Carl Perkins, Bo Diddley, Mac Curtis, Ray Campi and Sleepy LaBeef. Frontman Graham Fenton, in his earlier incarnation as a member of The Houseshakers, had worked with Gene Vincent on tour and in the studio.

Although The Sunsets had been briefly on Parlophone, and Crazy Cavan had looked poised for success on Charly, the bigger labels had largely ignored the revivalists, but Matchbox’s versatility enabled them to appeal to both older Teds and younger hep cats. Detecting a commercial opening after some of their A&R team caught one of the band’s shows at the Royalty in Southgate, north London, Magnet swooped to sign them to a contract.

The label had already enjoyed rock’n’roll chart success with Darts and Alvin Stardust. Taking Matchbox on board, who by now had settled on what was their classic line-up of Graham Fenton (vocals), Steve Bloomfield (lead guitar), Fred Poke (bass), Gordon Scott (rhythm and acoustic guitar) and Jimmy Redhead (drums) suggested a desire for something more rootsy. However, the Matchbox album and the band’s subsequent releases for Magnet reflected the difficulty larger labels had in accepting rockabilly’s mainstream appeal at face value, and carried the seeds of its rapid disappearance from the charts in the early 1980s.

The album tracks were cut at Wessex Studios in Islington, an old church hall. Graham Fenton admits it was a wow moment for the band when they walked in. The Sex Pistols had recorded Anarchy In The UK there, while The Clash (London Calling) and other punk and post-punk bands also used the studio, but incongruously it was a more established artist, Des O’Connor, who kept Matchbox waiting when they first arrived, as he was still finishing off a session.

The album’s producer, Peter Collins, went on to become a notable and respected name in the industry, and having graduated from making jingles for adverts, Matchbox were his first assignment. Having acted as their own producers on their previous album, Settin’ The Woods On Fire, they were to find his desire to add extras a source

of frustration.

The key track on the album, Rockabilly Rebel, was a Matchbox original, coming from the pen of Steve Bloomfield, who’d already proved adept at writing new songs for the band. Bloomfield’s lyric reflected the self-styled rockabillies, or hep cats, who were attending their gigs, with their flat top haircuts and quiffs. “We’d already been performing the song on stage before we got the Magnet deal,” recalls Fenton.

It was the obvious song to put out as their Magnet debut single, and that’s what the band pressed for. “Instead,” says Fenton, “the label wanted to go with the oldie Black Slacks, so we agreed to it on condition that if it didn’t happen they would put out one of our own songs, which would be Rockabilly Rebel.”

Black Slacks had been a Stateside hit in 1957 for Joe Bennett And The Sparkletones. An already gimmicky song was given a very 70s-style glam treatment, including a couple of the dancers from Top Of The Pops’ Pan’s People coming in to provide some female backing vocal support, which Fenton recalls dismayed the band’s fans.

“It was well produced, but it was also over-produced. It got quite a bit of airplay, but was tripped up by the fact that they released the original version and one by Robert Gordon at the same time.”

The failure of the undoubtedly catchy Black Slacks, the closing track on Matchbox, paved the way for the release of Rockabilly Rebel, which vindicated the band’s original judgement and gave them their first hit, peaking at No.12 in the UK charts in November 1979. With its chugging rhythm and the click of Fred Poke’s bass, it had a classic sound, which for once Collins largely left alone. Fenton recalls him suggesting fattening up his vocals in the chorus with double tracking. “So I had to go in and line-by-line put another vocal down to get the perfect match. It took quite a while!”

The resulting singalong effect feels not a million miles away from the sound of 50s skifflers, The Vipers.

Then there was the novel electric mandolin, played by Bloomfield, the inspiration for which came from Ray Campi, who the band had shared the bill with a few months before. “We asked Ray about his song Rockin’ At The Ritz. He said he was actually plucking on a fiddle on that, but that he also played the electric mandolin, so Steve said, ‘let’s use one’. Steve also loved to play an old Fender steel guitar.”

Buzz Buzz A Diddle It, pretty much a straight cover of Freddy Cannon’s 1961 hit, aside from the extra decibel levels of Fenton’s shrieks, was a song the band were already doing as part of their stage act. It gave Matchbox their second hit, reaching No.22 in January 1980.

Tell Me How was another note-perfect revival, with Fenton showing he could do Buddy Holly as well as Gene Vincent, and Gordon Scott and Jimmy Redhead using their doo-wop group backgrounds to superbly replicate The Picks on backing vocals. The only duff note was the way they sang a rising succession of “Tell me hows” on the bridge, an inauthentic intrusion which belongs to the 1960s beat era, not on a 1950s jewel record.

Bloomfield, who carefully recreated Holly’s lower-string guitar solo on Tell Me How, was also a creative writer and Love Is Going Out Of Fashion was a good example of glossy modern production techniques working to support an old-school nostalgic lyric. Yet even here, Matchbox experienced frustration, remembers Fenton. “Steve worked hard in the studio to get these different guitar sounds, and one he excelled on was Love Is Going Out Of Fashion. The album version has a spoken verse by me which I didn’t like, but we wanted it to go out as a single and spent hours on a remix, with slightly different lyrics and this knockout guitar solo by Steve. In the end, they just put it on the B-side of Midnite Dynamos. Steve was fuming. People used to ask, ‘Did you get Hank Marvin in to do that solo?’ It’s one of those ones that make the hairs stand up on the back of your neck.”

Everybody Needs A Little Love was another strong Bloomfield original, with washboard and fiddle lending an old-time feel, and vocal interplay from the band. They also excelled on Jerry Reed’s Lord Mr Ford, a country No.1 in 1973. Reed was a versatile country genius, but Fenton, a massive classic car fan himself, clearly enjoyed singing the humorous lyric, while Bloomfield shone on guitar. Fenton recalls a session at Red Bus Studios, where they added a few effects. “The band had a 1960s Humber Hawk with a lovely old-fashioned horn, and you hear the beep on the track. For that, Fred Poke was sitting in the car out in the street, while we were in the studio getting the right sound levels. This guy came out shouting and screaming at Fred, ‘What are you effing doing? You’re waking my kids up!’”

Hurricane was one of the weakest album tracks. Possibly never one of Bloomfield’s more inspired moments, we’ll never know thanks to heavy-handed production. Recalls Fenton, “We were late turning up at Wessex Studios that day, but when we arrived, there was one of the tape guys with Peter, who’d got a vacuum cleaner in the air conditioning unit with a microphone, just to get the hurricane effect. This sort of thing happened all the time with him. He didn’t do a bad production, but it was all the extras he’d add. I refuse to perform our version of Ray Campi’s Rockin’ At The Ritz anymore because the memory of doing the recording makes me cringe.” That said, if you can overlook the unnecessary backing vocal, it’s actually a well-crafted version of the song.

For all the shortcomings, Matchbox had a massive impact at the time, and it was a thrill to see a genuine rockabilly band on Tops Of The Pops. “The album opened a lot of doors and everybody flooded in,” recalls Fenton. With the imminent arrival of the Stray Cats, who took things to another level, “suddenly all the record companies were looking for rockabilly bands.”

Yet, he says, ultimately the Magnet stint left Matchbox stranded creatively. “We got pushed to the middle of the road.

Now, the middle of the road ain’t going to want a bunch of Teds or rockabillies doing their thing and by the same token we couldn’t get back to our own scene, apart from the really loyal fans. But we’ve gone back to our roots these days. When we do these songs now, we do them straight, the way we wrote them.”