Prompted by a lawsuit, John Lennon returned to his roots for a troubled covers album with producer Phil Spector running wild… By Martin Ruddock

In late 1973, John Lennon, former Beatle and sometime peacenik, was enjoying a second adolescence in Los Angeles. Interviewed by Melody Maker’s Chris Charlesworth, a relaxed Lennon was sanguine about his public separation from wife and muse Yoko Ono and move to the West Coast with new girlfriend May Pang.

Talking up the new project he’s about to start with Wall of Sound super-producer Phil Spector, an album of rock’n’roll classics from his youth, he tells Charlesworth: “Phil and I have been threatening to do this for years. I hope people won’t think I’ve run out of songs, but sod it, I just want to do it.”

In truth, Lennon was in delicate shape when he began cutting Rock’n’Roll in October ’73. His ‘temporary’ separation from Ono lasted 18 months. Relocating to LA, he’d fallen into a rowdy bachelor lifestyle and things quickly got out of hand. It was the beginning of his infamous “Lost Weekend”. Inner turmoil aside, the prospect of making an album of oldies during the nostalgic era of American Graffiti was a no-brainer for Lennon.

Throughout his career, he’d always returned to the 50s rock’n’roll of his teens as a reflex, even at the height of his John and Yoko avant-garde period. He was also creatively exhausted. Since The Beatles’ split, he’d made three albums of his own and one with Yoko, plus a brace of non-LP singles – also helping out with Yoko’s own records and experimental films.

There was also unfinished business dating back to 1969. Thanks to Lennon’s ‘borrowing’ of the lyric “Here come old flat-top” from Chuck Berry’s You Can’t Catch Me, for The Beatles’ Come Together, he’d been hit with a ruinous lawsuit from one Morris Levy in early 1970. Levy, known as ‘The Octopus’ due to his multiple business interests, pursued Lennon remorselessly, before finally settling out of court in late ’73, with agreement from John to record three copyrights held by his publishing company Big Seven on his next album.

Things didn’t go quite to plan. Interviewed again by Charlesworth again in early ’75, Lennon explained the hold-up. “Well, there was a psychodrama happening. It was called Phil Spector…”

In ’73 Lennon had gone into the sessions in good faith. Having previously worked with Spector at length and successfully curbed his more erratic tendencies, John planned simply to show up, bring a bottle and be the singer in a band composed of some of America’s finest studio cats. However, Lennon found Spector in full meltdown, drunk, raging and tooled-up.

John’s coping strategy was heavy drinking. A cacophonous out-take of Just Because features him drunkenly bawling the lyric and berating Spector between takes. One night Spector fired shots into the ceiling – inches from John’s head. An enraged Lennon yelled, “Phil, if you’re going to kill me, kill me. But don’t f*ck with my ears. I need ’em.”

The oldies album was put on ice when Spector vanished, taking the tapes with him. Resurfacing briefly in early ’74 as the Watergate scandal was breaking, Spector called Lennon, cryptically hissing, “I got the John Dean tapes.” Soon after, Phil was hospitalised after a major car accident.

In the meantime, Lennon went on a binge with Harry Nilsson that became an album (the Lennon-produced Pussy Cats). In the aftermath, he dialed back his hard-living and creatively recharged – making the slick Walls And Bridges in New York, including a brief version of Lee Dorsey’s Ya Ya as a concession to Levy, who was still waiting for his three tracks.

Meanwhile, after Capitol Records parted with $90,000, Spector finally surrendered the tapes in late ’74. With eight usable tracks in the can, Lennon and a seven-piece backing band entered the Record Plant to finish the album – now with the working title of Old Hat.

After presenting a rough mix to Levy, John was aghast to see a cheap bootleg mail order version of the album called Roots advertised on TV, available from Levy’s subsidiary label Adam VIII. Capitol sued, and the ‘Octopus’ backed down.

Rock’n’Roll finally emerged to mixed reviews in February ’75. One of the most scathing came from Phonograph Record’s Greg Shaw, who sniped: “Good as Sweet Little Sixteen sounds – it ain’t Buddy Holly, it ain’t Larry Williams, and it certainly isn’t Chuck Berry. And unfortunately, it’s not John Lennon either.”

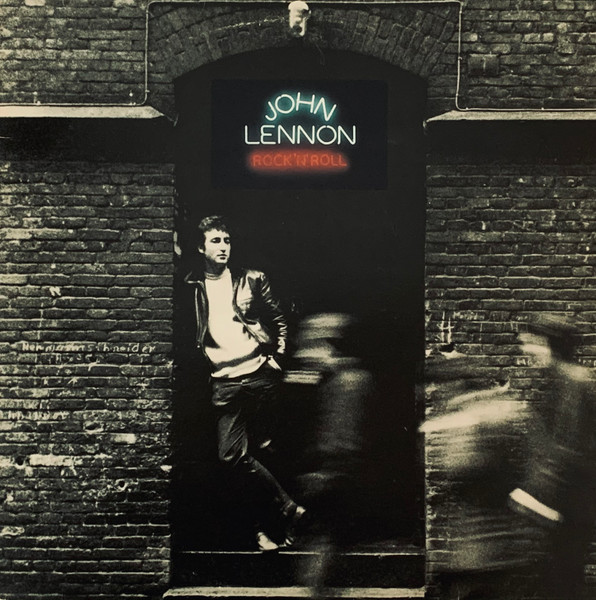

The LP’s sleeve pic came courtesy of The Beatles’ Hamburg friend Jürgen Vollmer, who snapped Lennon in 1960. Touchingly, the blurred figures in the foreground are Paul McCartney and George Harrison.

The album’s reputation over the years has been spotty, often seen as a chaotic vanity project from a genius songwriter running dry. But Lennon often drags triumph from crisis with some thrilling, raw vocals and inventive arrangements. Not everything works, but the sparse opener Be-Bop-A-Lula is full of tight, nasty slapback echo and expert rockabilly licks, while Lennon’s famous Be My Baby-style reinvention of Stand By Me is one of his finest solo cuts.

Most thrilling of all is Spector’s rampaging production of You Can’t Catch Me, the song that started the whole mess. Various outtakes from Rock’n’Roll have emerged over the years, while the original album has since had multiple revivals – most recently the gleaming remaster on 2010’s Signature Box. It’s not perfect, but it’s worth your time. As the great man once said, “Play Loud”.