The Beach Boys have amassed a wealth of material over the past six decades, from disposable novelty and feelgood hits to timeless genius. Here’s our pick of their finest sides… By Rik Flynn

America’s band”, the beloved clan that for legendary music scribe Lester Bangs presented “the most convincing argument in our entire culture for never growing up,” reside comfortably amongst the all-time greats, responsible for at least one of the world’s near-perfect albums. For the casual listener, The Beach Boys stand for surfing, cars, girls – and fun, fun, fun – but take time to dip below the surface and find a sweeping expanse of creativity to be unlocked.

Albeit rather hackneyed to repeat here, it’s genuinely true what they say: Brian Wilson really is a genius. At the crest of his dynamism he was a musician and songwriter willing – and able – to adventure far beyond the realms of pop. For an extremely fertile, rather manic, period, he flexed the boundaries of his imagination with each session until, rather tragically, his cup ran over – in part down to the drugs, in part due to the sheer scale of his ambition.

Yet even then, the rest of the band were able to take their cues from years of performing and recording his tunes, and were themselves able to grow to become worthy craftsmen and carry the mantle.

As one of the world’s longest running bands, they’ve soundtracked the diapason of the human experience: from the innocence of adolescence evoked via sun-kissed teen dreaming and endless summers to heartbreaking, existential epics that oscillate wildly across the spectrum of emotion.

There’s a convincing argument for many of The Beach Boys’ creations to be included here, but these 10 tracks go some way in representing the sheer brilliance of the band, testament to the scope of their artistic capabilities – all visionary, all stunning and all thrillingly unique.

10 I Know There’s An Answer, 1966

Cut with the working title of ‘Hang On To Your Ego’, its title and lyrics (written with tour manager Tony Sachen) were watered down when both Mike Love and Al Jardine expressed concern over the drug references, a worry shared by Brian. “I was aware that Brian was beginning to experiment with LSD,” recalled Mike. “The prevailing drug jargon at the time had it that doses of LSD would shatter your ego… I wasn’t interested in taking acid or getting rid of my ego.” The song’s makeup is centred around Larry Knechtel’s organ and Al DeLory’s tack piano in unison, with Tommy Morgan’s prominent bass harmonica up front (including the first solo of its kind in pop), 12-string and banjo played by a young Glen Campbell – and a woodwind ensemble.

9 Caroline, No, 1966

Brian met advertising copywriter Tony Asher in the studio where he was cutting a commercial, but when the call came to collaborate Asher thought it was a prank: “I hadn’t even dared to dream that I would be writing lyrics with somebody like that.” One product of this unlikely union was Caroline, No, Brian’s debut solo 45. Wilson’s plaintive harpsichord was augmented by a dozen sessioneers, including drummer Hal Blaine whacking an upside-down water bottle with a mallet. The identity of ‘Caroline’ differs depending who you believe, but Asher insists he pictured his high school girlfriend Carol Amen. Closing out Pet Sounds – with help from Wilson’s barking dogs – for Brian, it’s “one of the prettiest, most personal songs”, as he meditates on lost innocence.

8 In My Room, 1963

Written in just an hour with producer Gary Usher (who also co-wrote 409 and later worked with Brian in the 80s on solo material) as Brian was about to turn 21, this earnest ode to escapism is a summation of his early lyrical and musical style. Simplistic guitar picking, a flourish of harp, and we’re invited in to his solace, a respite from worries and fears – a place for crying, scheming, dreaming and reminiscing. Inspired by the night Brian taught his brothers to harmonise Otis Williams And His Charms’ Ivory Tower – a song they would then sing together “night after night” in their shared room back in Hawthorne – the track would find a home on the Surfer Girl album, and as the underside of the largely inferior Be True To Your School. There’s a German version too.

7 Don’t Worry Baby, 1964

Yet another classic coming-of-age fantasy, ably supporting I Get Around on the flip, Don’t Worry Baby was a woozy homage to Phil Spector, and closely mirrored Brian’s then-favourite record, the Spector-helmed classic, Be My Baby by The Ronettes, released the previous year. Penned with the help of radio jock and lyricist Roger Christian, Don’t Worry Baby’s similarly rolling rhythm and chord pattern make for a suitably starry backing that gave ample space to allow the group’s interwoven harmonies to float dreamily unconstrained, instantly evoking images of youthful lovers overlooking city lights through Cadillac windscreens. Cut in two separate sessions in Hollywood, and with a highly simplistic two-note guitar ‘solo’ (humorously credited as being ‘possible lead guitar’) supplied by shortlived early member David Marks, this made US No.17.

6 Wouldn’t It Be Nice, 1966

Having slipped the vinyl out of its rather down-home sleeve picturing goats at feeding time, the opening track bottled that innocence in sound. An imaginary ‘place’, visualised by Brian and collaborator Tony Asher, was embodied by Barney Kessel and Jerry Cole’s harp-like 12-string intro, before a giant roomy snare begins this earnest romance of two lovers set to the brightest of 60s sunshine pop. Once again Brian and Mike Love’s vocals spar with one another in bobbing partnership, while Dennis’ ‘cupped-hand’ backing added a unique slant within in a vocal mix that took a week to perfect. In amongst the melee – two pianos, three guitars, three basses, four horns, three saxophones, and a trumpet – it was the doubled-up signature “rockin’ accordions” that Wilson himself later highlighted. Chosen to open Pet Sounds – a testament to its quality.

5 I Get Around, 1964

That The Beach Boys – “America’s Band”– had their first Billboard No.1 on Independence Day 1964, couldn’t have played out more perfectly. Looking over the shoulder, this deceptively complex, yet utterly innocent, ray of adolescent sunshine encompasses all there is to love about the group’s early days, embodying the sandy Californian shoreline within its carefree harmonies. Written by Mike and Brian, who again offer the perfect counterpoint to one another here – Love’s playful verses and Brian’s rising falsetto – the track was cut during the session that ended their troublesome working relationship with father and manager Murry. Thanks in no small part to Mick Jagger’s endorsement, I Get Around secured a first UK Top 10, and a UK TV debut on Ready Steady Go!, the Boys in their striped Pendleton shirts enjoying a screamfest akin to Beatlemania.

4 Surf’s Up, 1971

The first many heard of Brian and Van Dyke Park’s astonishing 1971 single was on a CBS documentary hosted by Leonard Bernstein. Beautifully shot while the SMiLE sessions were underway, it’s a sublime performance, just Brian at his Chickering grand, eyes clamped shut, completely immersed in this inscrutable creation. Conceived in 1966 from the infamous sandbox at his Laurel Way home, whilst submerged in drug-taking, this was later completed for the 1971 album of the same name. Past the key and tempo shifts, Parks’ esoteric poetry – inlaid with high-brow references – made its grand theme of existential spiritual enlightenment all the more enticing. Its title references the loss of a bygone era, those virtuous teenagers a rosy memory. Wilson recut the song for his 2004 version of SMiLE.

3 California Girls, 1965

This teen salute to the girls of the USA may seem little more than catchy, sun-kissed pop on the surface, but it was a decisive moment in the timeline that showed Brian seriously upping his game. He was just 22 when, with cowboy films and fashion magazines bouncing around his head, he conceived the intro sat at his piano, midway through his first trip. With The Drifters’ On Broadway often cited as his springboard, Wilson realised his first truly ambitious opus aided by his now-regular LA sessioneers, assembled, as ever, at Western Recorders, with Mike Love scribbling lyrics in the corridor outside. The six-part harmonies were added later – including from new member Bruce Johnson. “I knew that would become the theme song of The Beach Boys,” said Wilson, calling it “the greatest piece of music that I’ve ever written”.

2 God Only Knows, 1966

Reportedly written in under half an hour, Wilson recorded God Only Knows with the help of a whopping cast of 23 top-flight musicians at Hollywood’s Western Recorders in spring 1966. Listen to the session tapes and find Brian in complete command, issuing instructions from the control room mic, while still open to suggestions from the assembled musical minds. In the room are Alan Robinson, whose majestic French horn introduces the song, and Hal Blaine once more at the kit, who, together with Lyle Ritz on string bass and Ray Pohlman’s picked electric bass, provides the rhythm. Piano, harpsichord, a layered flute and string section – and even an accordion – added sumptuous textures. It’s a pivotal, spiritual exclamation of love that regularly reduces Macca to tears, while, for Bono, it’s “proof that angels exist” – high praise indeed.

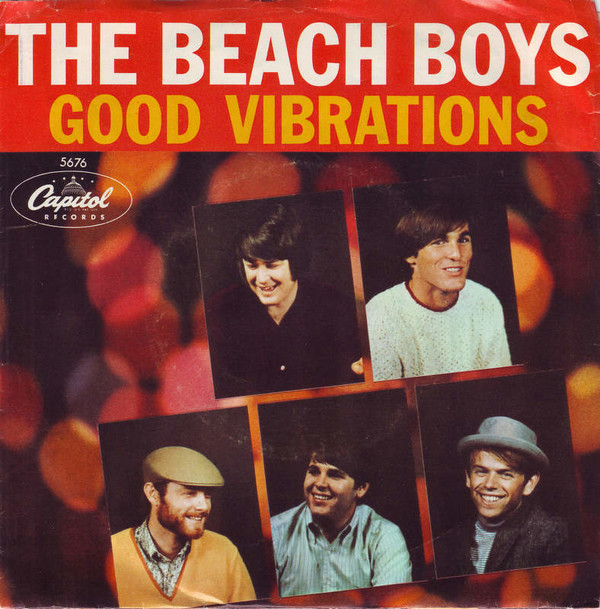

1 Good Vibrations, 1966

With one eye on The Beatles, Brian Wilson set out to master his personal rendering of Phil Spector’s ‘wall of sound’ with his most formidable vision yet. Conceived while Pet Sounds was being recorded, but deemed incomplete at the time, Wilson intended Good Vibrations to obliterate convention and challenge the very fabric of pop. Its unique structure was fashioned using a collage of fragmented ideas – segments Brian called his ‘feels’ – expertly interwoven. Innovation came at great expense, however. Wilson’s “little pocket symphony”, a vox-pop coined by savvy publicist Derek Taylor, was rumoured to cost a staggering $50,000, thanks to months of sessions at Gold Star, Western Recorders and Sunset Sound studios, some lasting mere minutes, others six hour-long marathons. While Wilson conducted affairs, his regular roomful of LA’s finest helped shape the complex tapestry of flutes, cello, harpsichord, Jew’s harp, electric and upright bass, tack piano, bass harmonica, chromatic harmonica, organ, guitar – all that, plus Paul Tanner’s unearthly Electro-Theremin (a simplified version of Leon Theremin’s original instrument) literally harnessing the vibes. Tony Asher’s lyrics were based on Wilson’s memories of his mother explaining how dogs picked up on vibrations, “invisible feelings” that scared Brian half to death. Mike Love sweetened the pot with his own hippyish imagery – colourful clothes, a blossom world – combining to create a subversive, joyous masterpiece – the maestro’s finest moment and Brian’s final No.1.