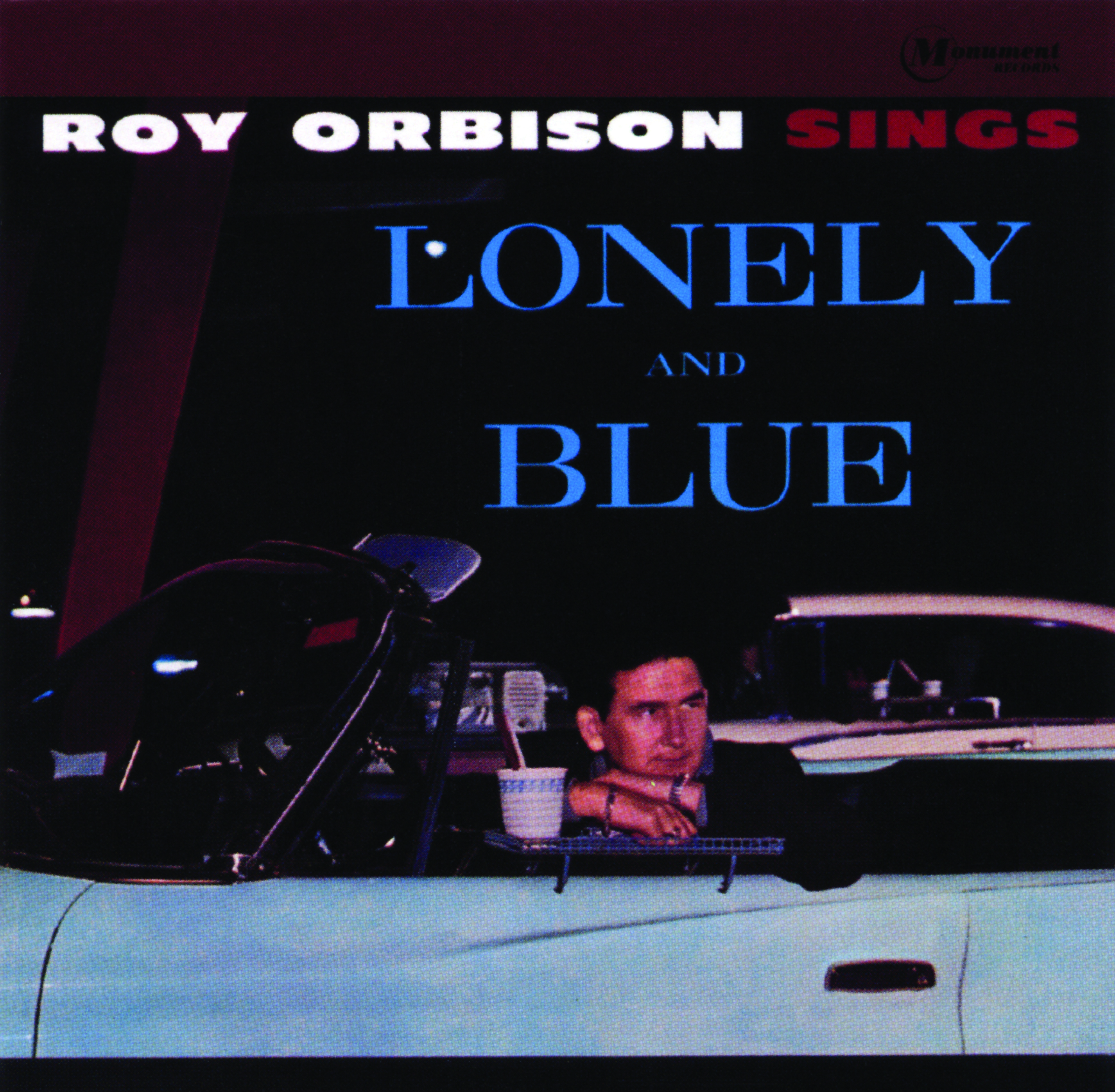

Roy Orbison’s emotive studio album reflected the early fruits of his revitalised recording career with Monument Records, which left his frustrations with the Sun and RCA labels behind him. By Jack Watkins

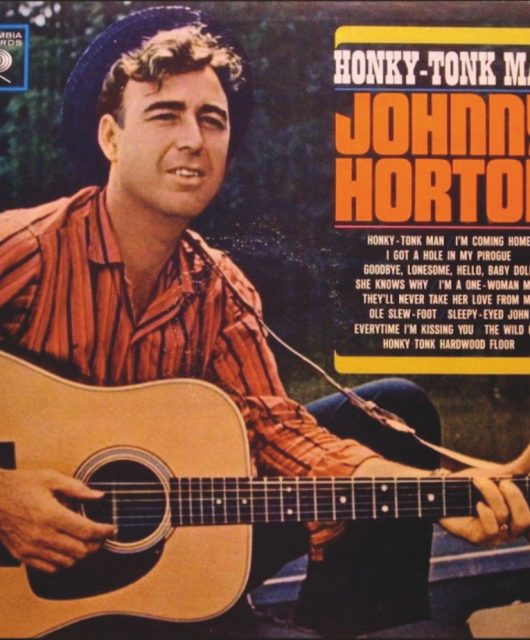

If Elvis Presley was the King, Roy Orbison was the King of Wimp Rock. Lonely And Blue, released in January 1961, formalised his ascendancy to the throne, a process prefigured by the enormous success of the single Only The Lonely (Know The Way I Feel) the previous summer. However, it’s not quite true that Orbison ushered in a totally different, non-macho type of male rock or pop star. Johnnie Ray had emoted more than any white male singer in the early 50s. Presley, with his androgynous appearance, had never been afraid to show his vulnerable side either. Meanwhile, Buddy Holly had already proved you could look geeky and still get to the top.

It was also Holly, in the late recordings he made in New York in 1958, who had turned away from the constrictions of the simple electric guitar and drums rock’n’roll template to work on a broader sound canvas similar to that which Orbison would turn to for the material on Lonely And Blue.

Holly was a limited vocalist, however, whereas Orbison was one of astonishing range, and this is where his true difference lay. Among the stars to emerge out of early rock’n’roll, he was gifted with the ability to deploy his fabulous voice on songs whose melodies spoke to different generations, while connecting with the yearning and loneliness of youth. Compositions such as Only The Lonely, I’m Hurtin’ and Blue Angel, all featured on Lonely And Blue, and later singles like Crying, Running Scared, Falling and It’s Over surely say as much about the internal agonies of adolescent desire and love in the 60s as anything by The Beatles or The Rolling Stones.

Orbison also reminded those who bought his records or attended his shows that the ballad was just as powerful and satisfying a medium of conveying otherwise inexpressible feelings as any souped-up rock song, and that bigger orchestrations with strings were still a legitimate part of a young musician’s armoury. It took guts and perseverance to bring this off, however.

Orbison always knew, right from the time he went into Norman Petty’s tiny studio in Clovis, New Mexico, in 1956 to make his first recording, that he had a distinctive voice. “When I heard my voice back on record,

I didn’t think of it in terms of good, bad, or indifferent, only memorable,” he recalled in an interview near the end of his life. “It’s a voice that once you hear you never forget.”

Yet he’d struggled at Sun, despite making outstanding recordings such as Devil Doll and Sweet And Innocent, because as Orbison put it, Sam Phillips “wanted everything up fast, or in a particular vein”. It was bad enough that producer-engineer Jack Clement told him: “Don’t ever be a ballad singer. You’ll never make it”. Orbison was also frustrated by Sun’s basic recording conditions. That wasn’t the case with Monument Records where, after a brief spell with RCA, Orbison had arrived in 1959.

Despite his own limited means, Monument’s founder and producer Fred Foster gave Orbison the support he’d been denied at Sun and RCA. “I wanted to use violins, and since I’d had such a rough time at Sun trying to get what I wanted, I was really ready to fight for violins,” Orbison recalled. “And Fred said, ‘OK, no problem’.”

It helped that Foster liked the shy but determined man from West Texas. “He had a great deal of humility. You couldn’t have asked for a more pleasant person to be around,” Foster remembered. It probably helped even more that his new signing was soon shifting records. Although Orbison’s first Monument single Paper Boy was an insipid dud, he quickly acquired a writing partner in fellow Texan singer and writer Joe Melson, and the fruits of the new pairing were borne with the minor hit Up Town, released at the end of 1959.

That was nothing compared to what was to follow. Only The Lonely, track one on Lonely And Blue, was the song that kickstarted the legend of Roy Orbison. It began as a fragmentary piece that Melson had been working on before showing it to his new writing partner. After working it up a little further, they had unsuccessfully pitched the song to Elvis and the Everly Brothers, who’d already had a hit in 1958 with a track Orbison had written for them, Claudette. Not deterred by this minor setback, Orbison decided to record the song himself at his third Monument session, in March 1960. Although Foster, lacking his own facilities, had to use RCA’s Studio B in Nashville to record Orbison, he didn’t cut corners on employing accomplished sidemen or on sound quality. Crack Nashville session men such as Hank Garland and Harold Bradley on guitars, Bob Moore on bass and Floyd Cramer on piano played on the Only The Lonely session.

Another Nashville stalwart, engineer Bill Porter, adroitly used close-mic’ing techniques to get the best out of the backing vocalists Orbison so loved to use – in this instance the Anita Kerr Singers, along with Joe Melson.

However, there was disagreement when Foster voiced concerns that this rock-a-ballad had an odd 2/4 time signature, which rendered it undanceable. Orbison stuck to his guns, retorting: “I never wanted to dance to any of my songs, I just want to sing it, and this is the way it goes.” But Foster’s suggestion of lifting the “dum-dum-dum-dummy-doo-wah” choral refrain from another Orbison/Melson composition Come Back To Me (My Love) and placing it over the introductory bars of Only The Lonely proved less contentious. After the recording was completed, “We all gathered round and listened to the playback,” remembered Foster, “and with goosebumps on my arms, I turned to Roy and said, ‘There’s your big hit’.”

With its gentle Latin rhythm and stuttering middle-eight, Orbison had at last found a suitable vehicle for his spectacular vocal range, which ran from that of a baritone to a tenor. As Foster had predicted, he was rewarded suitably. The song reached No.2 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the summer of 1960. In Britain, it was the definitive sleeper, taking several weeks after its release to enter at the foot of the Top 30 at the end of August and only getting to No.1 in the second week of October.

By the time Lonely And Blue was released at the start of the following year, Orbison had followed up with two more hits, Blue Angel and the more modestly successful I’m Hurtin’, both featured on the album. The peachy Blue Angel, an Orbison/Melson original, was a Top 10 hit in the States, and made the Top 20 in Britain, while Only The Lonely was still in the charts at the end of 1960. It was blessed with another infectious, doo-wop inspired intro delivered by the Anita Kerr Singers. Another original song, I’m Hurtin’, somewhat less successful as a single, drew an emotional Orbison vocal, the singer howling an almost coyote-like “you walked away-eee”.

However, the overall effect of Lonely And Blue placed it very much in the Nashville Sound country vein, reflecting Foster and Orbison’s desire to make an album that appealed to a broader market than just lovesick teenagers.

Although comprised of tracks recorded over a six-month period, Lonely And Blue saw the long-player performed by an artist emerging out of the rock’n’roll field – so often to this point a format constructed from a slew of a hits – finally coming of age.

The album was split between Orbison-Melson originals and several cover versions. If Only The Lonely’s “only the lonely know the way I feel tonight” was a line any lovestruck teenager could have related to, Bye Bye Love, the second track on the record, was an already-proven hit with youngsters, the Boudleaux and Felix Bryant composition having brought the Everly Brothers their first big chart success on the Cadence label in 1957.

Despite obvious spiritual parallels between the music of the Everlys and Orbison’s, the latter’s cut didn’t quite match the glistening innocence of the original. While the lap steel guitar, played by one of the instrument’s pioneers, Jerry Byrd, emphasised Orbison’s country kinship, the big Foster and Orbison production values were a little too much, with fussy strings and the Anita Kerr Singers’ answering call of “bye-bye” unnecessarily intrusive.

The big sound was better suited to Orbison’s take on the Johnnie Ray hit Cry, which was very much in the countrypolitan vein. Orbison didn’t attempt to replicate the histrionics of Ray’s recording, leaving most of the second half of the song, which Ray belted out so memorably, to the strings and Byrd’s guitar.

Similarly countrypolitan in feel was Blue Avenue, which had been recorded at the same session that yielded Only The Lonely. Saxophonist Boots Randolph, another Nashville session ace, who played on hits such as Brenda Lee’s Rockin’

Around The Christmas Tree and Presley’s Return To Sender, as well as Orbison’s later smash Oh, Pretty Woman, was on good form on the track and there was an expressionistic, almost noirish feel to the strings arrangement.

Two tracks that showed Orbison didn’t have to resort to semi-operatic vocal gymnastics to move his audience were the masterly but straight recordings of a pair of Don Gibson songs, I Can’t Stop Loving You and (I’d Be) A Legend In My Time.

However, the album wasn’t without a few flaws. Come Back To Me (My Love), even if Fred Foster loved it, showed that if the standard dropped, the essentially self-pitying nature of Orbison’s songs could slip into mawkish slush. Raindrops was even weaker, though mercifully clocked in at under two minutes, unlike Twenty-Two Days, written by Gene Pitney, which ran to just over three but felt much longer.

Thankfully, these were the album’s only low points. The LP’s closer, the resigned and reflective I’ll Say It’s My Fault, concluded with a subdued Randolph sax coda rather than a dramatic vocal finish from the Big O. In fact, in the light of subsequent vocal masterclasses such as Running Scared, Crying, In Dreams, Falling and It’s Over, Orbison’s singing on Lonely And Blue was for the most part relatively restrained.

Although the album did not chart in the States, it reached No.14 in the UK. The British love affair with this remarkable artist was well and truly under way.