Dale Hawkins’ Susie-Q was one of the finest songs to emerge out of early rock’n’roll, a swamp-rock classic. Yet the artist himself remains relatively under-appreciated, as does his seminal debut album… By Jack Watkins

Dale Hawkins was something of an oddball among early Southern rockers. Almost by definition, of course, most of them were oddballs and offbeats. That’s what made their sound unique. Yet Hawkins stood apart from the others by disdaining the country music in which most of them claimed to be rooted, while playing up the African-American blues influence. As he related to Bill “Hoss” Allen, a Nashville DJ who championed R&B, in 1958: “I could never be a country & western singer. I got to have that beat.”

You could even argue the toss about whether Hawkins really qualified as a rockabilly in its purest definition. His biggest number, Susie-Q, had a floor-shaking blues riff straight out of the Howlin’ Wolf playbook and the click of a slap bass was seldom heard on his records. Hawkins eschewed that instrument in favour of an electric bass because, overlooking the fact that Willie Dixon played double bass on many Chicago blues numbers, he wanted to get a more authentic sound.

Additionally, Hawkins was a mediocre singer lacking the definitive vocal signature that was stamped all over the work of great Southern rockabillies such as Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent, Mac Curtis, Warren Smith and Sonny Fisher. Instead, Hawkins was blessed merely with a soda-pop squawk, passable when the material was up to spec, completely forgettable when it was sub-par.

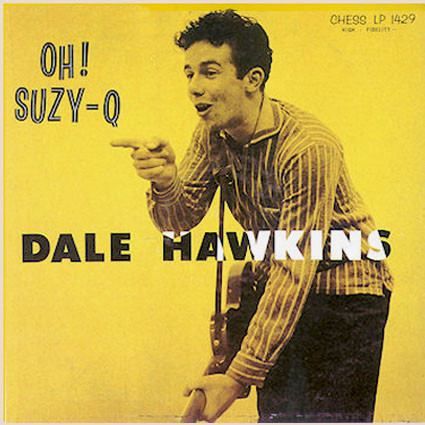

But Susie-Q was a creation of near undefinable genius, up there with Heartbreak Hotel, Be-Bop-A-Lula, Somethin’ Else and Great Balls Of Fire as bar-raising hybrids which, despite their outward simplicity, defy easy journalistic summation. Some people have hailed the song as kicking off the whole new sub-genre of swamp rock, though this was not a recognised term at the time. Undoubtedly, however, the LP Oh! Suzy-Q, released by Chess in October 1958, complete with a cover which either deliberately misspelt or re-spelt its title track, was a genuine, wall-to-wall rock’n’roll album, with no concessions to squaresville.

That’s not to say Hawkins had taken time out to cut an album, as would later become the practice. The songs were lifted from sessions in Shreveport, in Hawkins’ native state of Louisiana, and the Chess studios on South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, between 1956 and 1958. The Shreveport tracks were cut at the KWKH studios, famous for broadcasting the Louisiana Hayride, during the radio station’s downtime. Hawkins, after a stint in the US Navy, had arrived in the town in 1956 and got a job in Stan Lewis’s Record Shop.

Already familiar with the rhythms of spirituals and blues songs from his days working alongside black field hands picking cotton, Hawkins’ knowledge and enthusiasm came in handy with shoppers looking for the latest hot R&B platter. But Lewis was also a talent scout for Chess Records, who knew that if Lewis, with his ear on the local market, told them a record was selling in Louisiana, it was a nailed-on hit. As Hawkins was showing early signs of promise with a band featuring 15-year-old local boy James Burton, who’d already played electric guitar at the Hayride, Lewis got him a couple of demo sessions. One was at another Shreveport radio station, KENT, at which an early version of Susie-Q was recorded, and a second was at KWKH, at which were cut the two most venerable recordings on the 12-track Oh! Suzy-Q album, See You Soon Baboon and Four Letter Word-Rock.

After Lewis sent the demo tapes off to Chess Records, these latter two recordings were paired to make the first Dale Hawkins single, put out on the Chess subsidiary label Checker in the summer of 1956. Both songs adhere to what was a pretty familiar R&B and jump blues-type formula at the time, with big, belting tenor sax solos. See You Soon Baboon was an attempt by Hawkins to cash in on a record by fellow Louisianan Bobby Charles. The first white artist to be signed by Chess, unwittingly because Leonard Chess had signed Charles sight unseen, thinking he was a black singer, the boy from the bayou had just enjoyed an R&B hit with See You Later Alligator, although it was massively outsold by Bill Haley’s version.

See You Soon Baboon was Hawkins’ answer song, delivered with a quirky panache far beyond anything the insipid Charles ever managed. Only a moderate seller, spliced to the beginning and end of the track was a Tarzan-style yell, courtesy of DJ Gene Nobles who was owed a favour or two by Chess at the time. That was deemed enough to drop Hawkins’ name off the songwriting credits, which was attributed to Stan Lewis, along with Nobles’ wife Eleanor Broadwater.

It was almost a year before a follow-up single, the mighty Susie-Q, was released, and even then only after Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler, who’d heard a tape of the song, threatened Chess that if they didn’t put it out, he would. The single version, recorded at 1am at the KWKH studio early in 1957, was notably different from the KENT demo. Gone was the sax solo, as was drummer AJ Tuminello, who couldn’t make the date. But, thankfully, Hawkins made sure his replacement, Stan Lewis’s 15-year-old brother Ronnie, replicated the unforgettable drum and cowbell accompaniment that Tuminello had improvised one night during a band soundcheck.

Hawkins, his ears pricking, had excitedly instructed the drummer, “Man, hang on to that!”. Also retained, though more effectively worked up, was James Burton’s stinging lead guitar. The electric bass was played by Sonny Trammell, a Louisiana Hayride regular better known as a steel guitarist.

The entire song was a composite rather than a composition. Some said Hawkins got the idea for the title when he saw a Howlin’ Wolf show in Shreveport in which he rolled around the floor moaning the name “Susie,” though Hawkins refuted this. But Burton’s riff certainly sounds like the guitarist had heard Hubert Sumlin’s work with Wolf, not least on Smokestack Lightnin’.

Hawkins did admit that the main melodic influence was The Clovers’ I’ve Got My Eyes On You. It’s fair to argue that these white teenage lads came nearer than any other ensemble at the time to successfully capturing the raw and earthy intensity found in the work of blues maestros such as Muddy Waters. As one

of Hawkins’ greatest champions, the writer Bill Millar, has observed their song had “forged a new and largely inimitable departure from rockabilly”.

Interestingly, the record contains a mistake. Bob Sullivan, a lynchpin of the Shreveport recording scene, was the engineer on the KWKH session. He later recalled that there were four takes, and that Hawkins picked the wrong one for release, given it was an early take in which Sullivan was still fiddling around trying to establish the correct sound balance. Not realising Hawkins had started singing, Sullivan had to hurriedly turn up the volume control on his mic. Listen closely and you’ll hear Hawkins’ vocal feeding in abruptly over Burton’s intro riff 15 seconds into the track.

Susie-Q was rewarded with a No.27 placing on the US pop charts. Hawkins made an appearance on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, minus the band and miming awkwardly. His moves were more Jacques Tati than Elvis Presley, but it was the song that mattered, and when he played Harlem’s prestigious black venue the Apollo Theatre, he was the only white artist on the bill. That said everything about the credibility of his music with black listeners. He’d later relate how he’d get phone calls “from black moms and they’d say… I should work on my diction for my race!”

Once again, Lewis and Broadwater were handed writing credits, and while Hawkins was, too, Burton was left off. “At 15, what do you know about the business?” he’d ruefully reflect. “You’re doing something you really love and enjoy. The actual guitar lick was mine, but you live and learn in the business.”

Hawkins never had a hit on the scale of Susie-Q again, but he enjoyed moderate success for the remainder of the decade. Several of his singles fetched up on Oh! Suzy-Q. Among the best was the Susie-Q follow-up Baby Baby, another cowbell cracker, if lacking the spark of originality that denoted its predecessor. Truly excellent were Tornado and Little Pig. The former, with its heavy, loping beat, halting rhythm and whammy bar quiver, had something of the oddness of Susie-Q and Hawkins delivered one of his most potent vocals.

By now, Burton had left the band, but Hawkins never had trouble attracting guitar talent, and the parts on the song were supplied by Carl Adams and Kenny Paulsen, who’d shortly play on Freddy Cannon’s Tallahassee Lassie. Little Pig was destined to become one of the beloved songs of the rockabilly revival, with versions recorded by Buzz & The Flyers and, most memorably, the Polecats for their Polecats Are Go! album of 1981. The latter takes some beating, but for syncopated cool, the original remains definitive. The unison vocals in the chorus were supplied by Margaret Lewis and her sister Rose.

The sisters, who’d also contributed to Tornado, were on duty again for the stomping Juanita, which featured another fine guitar solo and piano work possibly by Lafayette Leake, who graced the recordings of just about every artist who recorded for Chess, from Little Walter to Chuck Berry. The catchy clapping rhythmic augmentation was an effect used on some of Gene Vincent’s best sides.

Oh! Suzy-Q didn’t shift a lot of units at the time and it’s something of a forgotten album, with the name Susie-Q more familiar to most people than the man behind its creation. The song was covered by several big names, most notably Creedence Clearwater Revival in 1967, when John Fogerty was searching for something he termed as “classic guitar rock’n’roll” for their first single.

This simmering version practically out-swamped the original. The Crew-Cuts released a tame homage, while The Rolling Stones’ R&B take sounded tinny and thin in comparison. The version cut by Dale’s cousin Ronnie Hawkins was similarly hamstrung by a 1960s R&B pastiche sound. José Feliciano’s slowed-down attempt in 1970 showed that if you’re going to revisit a perfect recording, you need to be bold.