We remember the fifth album by Bob Dylan’s former backing back, the sublime Moondog Matinee… By Steve Harnell

The covers album – a last refuge of the creatively bankrupt or a chance to blow away the studio cobwebs for the next chapter in a recording career? For The Band and 1973’s Moondog Matinee, it was arguably a combination of the two.

Having not toured for two years and with lynchpin piano player Richard Manuel mired in drink and drug addictions, the most critically-acclaimed US group of their era weren’t exactly firing on all five cylinders.

Their much-vaunted brotherhood, which had driven the collective strength of their first two LPs, was slowly evaporating. It was time for The Band to lighten up and have some fun.

Main songwriter Robbie Robertson had something of a creative block, too, hamstrung by an inability to get his ambitious Works project – a multi-layered symphony about the plight of the Native Americans – off the ground. Meanwhile, drummer Levon Helm, frustrated at The Band’s stasis, enrolled at Berklee College of Music during the winter of 1972.

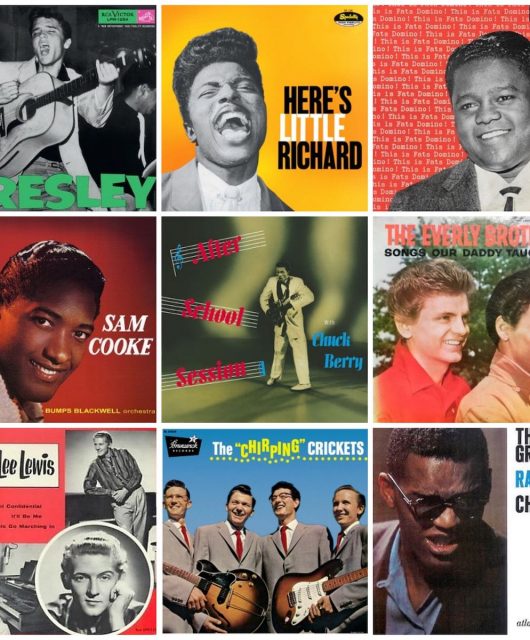

As a solution to their travails, Robertson hit upon the idea of The Band reconvening to record rock’n’roll and R&B favourites that saluted their Toronto roots as backing group The Hawks with rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins.

“With American Graffiti coming out and radio stations playing a lot of those old records, it was becoming valid music all over again. People were feeling nostalgic… and they were picking the past apart again,” Robertson explained.

“I remember some consternation when we heard John Lennon was doing the same thing with Jesse Ed Davis and Phil Spector, but this was indicative of the low level of creative feeling in 1973 and an instinctive need to get back to rock’n’roll’s pure roots,” added Helm in his autobiography This Wheel’s On Fire.

The ‘Moondog’ element of the album’s title was a reference to Alan Freed’s Cleveland radio show Moondog’s Rock’n’Roll Party, while ‘Matinee’ referenced The Hawks’ “torrid afternoon shows we used to do in Toronto for the teenage girl crowd 10 years earlier, a much simpler time,” offered Helm.

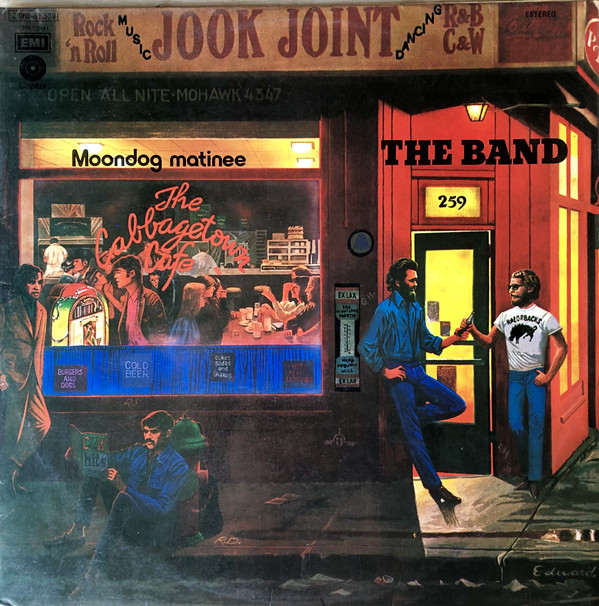

The sleeve, by Canadian artist Edward Kasper, was inspired by the Toronto neighbourhoods where Robertson grew up, and showed The Band hanging out at a corner juke joint.

After spending a fortnight sifting through potential material, tracks such as Larry Williams’ Bony Moronie were jettisoned and possibles including Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever and Slippin’ And Slidin’ similarly given a swerve. The Band settled on a core selection and divvied them up to play to each vocalist’s strengths: drummer Helm took the upbeat Southern rockers, Manuel was assigned the melancholic ballads, while bassist Rick Danko fronted the melodic mid-tempo numbers.

Recording sessions were mostly undertaken at Albert Grossman’s Bearsville Studios near The Band’s Woodstock base between March and June 1973, before the album was mixed that August for an October release.

Opener Ain’t Got No Home, a hit for Clarence “Frogman” Henry in the winter of 1956-57, boasts great tenor sax work and boogie-woogie piano from Garth Hudson (a nod to Lee Allen and Herb Hardesty, perhaps); the whole arrangement really swings.

Helm’s deadened drums keep the sound tight and compressed, while Hudson rigged up a talk box hose for Levon to sing through for the track – a vocoder effect three decades before the fact. Helm claims he played bass on the song, with a double set-up of Manuel and the Mothers Of Invention’s Billy Mundi on drums.

Danko serves up a typically emotive vocal performance on Lee Dorsey’s Holy Cow, The Band making the track their own to such an extent that it sounds as if it could have been culled from either of their first two studio albums.

Share Your Love With Me, originally recorded by Bobby “Blue” Bland and a song the fivesome played live back in their days as The Hawks, exquisitely exploits Manuel’s soulful falsetto.

The centrepiece of the album is Little Junior Parker’s 1953 hit for Sun Records Mystery Train, covered by Elvis two years later. Recorded at Capitol’s Hollywood studio, it’s a galloping rocker with another terrific swaggering vocal from Helm that also features two new verses penned by Robertson, who sought permission from Sam Phillips to allow the changes.

The typically resourceful Hudson weighs in with train-like sounds on wah-wah effect-laden clavinet and organ. Meanwhile, there’s a change of pace for the quirkily tongue-in-cheek The Third Man Theme, a typically left-field choice from Hudson, who supplies twinkly background keyboard work.

Helm pretty much bosses the album vocally. He’s on crackling form for a powerful take on Chuck Berry’s Promised Land, which also boasts rollicking rock’n’roll piano. He also shines on the no-frills Fats Domino rocker I’m Ready, complete with a mesmerising piano solo and swinging sax break from Hudson.

Manuel mines the emotional heart of The Great Pretender, too – there’s none of the bravado of the later Freddie Mercury version. Manuel’s contributions often had relevance to his own tortured life, see also The Shape I’m In on the Stage Fright LP.

Yet the message of the Leiber & Stoller gospel rocker Saved failed to translate to his own demons; Manuel battled various addictions before committing suicide in 1986. Ambitious closer A Change Is Gonna Come is a delicate take on the Sam Cooke classic as Danko amps up its existential angst: “It’s been too hard living, but I’m afraid to die…”

Moondog Matinee limped to No.28 in the US and didn’t chart in the UK. “It’s the only album I’ve ever heard of old rock’n’roll songs where I thought the interpretations came anywhere near complementing the originals,” Robertson told Harvey Kubernik. “Unfortunately, people compared it to everything else we’d done, which I thought was ridiculous.”