‘It may not be American, but it’s ours’ thought British teens as wannabe rockers emerged from the UK suburbs. At the forefront was Marty Wilde, who recalls cutting his own 1959 debut LP with a sense of the impossible…

It’s a badge of honour among some in the rock’n’roll fraternity that they never touch the early British stuff. It’s true that much of what was made over here was derivative and reliant on re-recordings of American songs. But while many efforts at recreating the sound of American rock in British studios in the late 50s were laughable, no less daft is the view that nothing worthwhile came from the homegrown response to the phenomenal new sounds coming out of the States.

The godfathers of the music on this side of the Atlantic are Lonnie Donegan, whose early skiffle recordings were rock’n’roll in spirit and energy, Marty Wilde, Cliff Richard and Billy Fury, followed by Vince Taylor and his Playboys, and Johnny Kidd & The Pirates. They weren’t all teenagers, but all made recordings that stand in their own right, while retaining something peculiarly British. Others such as Tommy Steele, Wee Willie Harris, Terry Dene, Vince Eager, and even Tony Crombie, merit honourable mention, too.

“To be honest, I wouldn’t want to hear Cliff’s Move It played by a proper rock’n’roll musician. It wouldn’t have sounded the same” – Marty Wilde

None of them, to be fair, except perhaps Donegan, claimed to be producing work on a level with their American inspirations. Marty Wilde, publicly critical at the time of the sound on many of his 50s singles, remains so today. “Yeah, well, they all had their own style in the end,” he reflects. “But, to be honest, I wouldn’t want to hear Cliff’s Move It, for example, played by a proper rock’n’roll musician. It wouldn’t have sounded the same. It was similar with my own hit version of Endless Sleep. They were, for me, two songs of the era that sounded right, that sounded like we’d got it.”

Unlike the young white American rockers, Wilde and his cohorts didn’t have the advantage of some old black guy sitting in the porch teaching them a few blues licks, or even much idea of live rock’n’roll performance before they faced the ordeal of entering a studio and nudging more seasoned musicians towards the new style. As Wilde says, “It wasn’t like we were living near Beale Street… we were from places like Hounslow or Greenwich. You had to feel the thing yourself.”

But, despite a lack of formal training, Wilde had a well-developed musical ear. He’d picked up harmony singing from his father as a child, and at secondary modern school a music teacher had introduced him to classical music. As a teenager, he describes going to a record shop in his native Greenwich as “like entering a cave full of diamonds.” The owner sold him the latest Bill Haley and Elvis Presley singles, and introduced him to the blues of Big Mama Thornton and Muddy Waters. “It gave me a slight advantage, I feel, and I have always had an appetite for music of all kinds. I’m a lucky man in that way because a lot of people in the rock’n’roll world were just rooted into that one style.”

“Endless Sleep was moody, and I had a kind of sulky, moody face. I was that sort of man back then” – Marty Wilde

And, like many rockers of his generation, he knew how to carry a tune, adoring pre-rock’n’ roll singers like Frankie Laine and Guy Mitchell. “I loved Frankie Laine to bits. Tracks like Blowing Wild (The Ballad Of Black Gold)… so very dramatic, such powerful stuff. That sense of drama was one of the things I picked up from him.” Wilde later recorded Jezebel as a tribute to Laine, adding a superb new pulsing rhythm, which got him his last Top 20 hit in 1962.

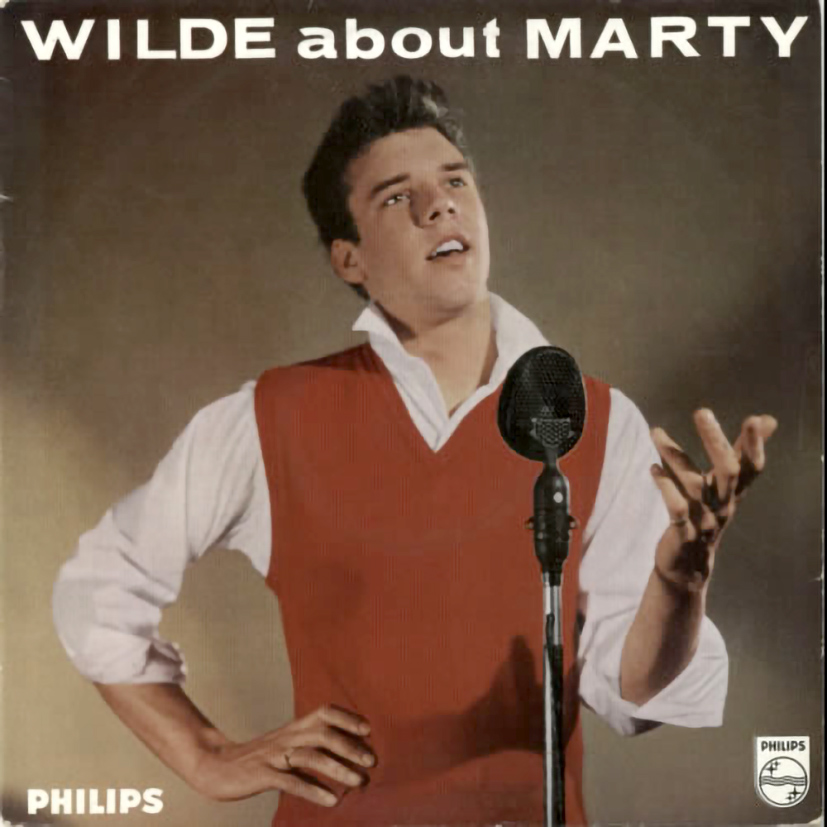

Wilde’s all-round musicality is evident in the singles that led up to his debut album, Wilde About Marty, released in September 1959. Signed to the Philips label, his first single, Honeycomb, came out in October 1957. A cover of the Bob Merrill-penned Jimmie Rodgers hit, it’s been written down by some. But that’s just another example of the default tendency, especially prevalent in the 1950s, to assume something American must always be better. In fact, Wilde was clearly the superior singer, and accordingly, so is his version of Honeycomb. He penned the flipside, Wild Cat, and while he dismisses it as “just a young guy writing rock’n’roll”, it’s a good example of British efforts to make Bill Haley-esque rock. Wilde’s boyish, pent-up energy works well, played off against the slightly stiff horns, and Bert Weedon’s clean, jazz-based guitar.

Endless Sleep gave the singer his breakthrough hit, rising to No. 4 in the summer of 1958. Again, miles better than the Jody Reynolds original, Wilde invested it with real melodrama. “It was moody, and I had a kind of sulky, moody face,” he recalls. “I was that sort of man back then, so it suited me image-wise, sound-wise, story-wise.”

“They could get great sounds and yet they were only using little four-track machines” – Marty Wilde

The guitarists on the session were Weedon, again, and Ernie Shear, soon to work on Cliff’s Move It. “But it was Bert that did that ‘ba-a-ung’ intro. To start with, they were playing it as ‘jay-ing’, using chords, but I said, ‘Bert, there’s a guy called Duane Eddy who is playing all single notes on the bass strings. Can you do it like that?’”

Less convivial towards the 18-year-old Wilde was seasoned jazz drummer Phil Seamen. “We had a right bust up,” Wilde remembers. “We started the song, and after the guitar came in, I could hear this swishing sound. Phil was playing the drums with brushes. I thought: Silly sod, what’s he doing? So I said, ‘Excuse me, can we have sticks?’ He said, ‘Whattt?’ I said, ‘Can we have sticks, instead of brushes? We’re playing rock’n’roll, and it just doesn’t sound right to me.’ He just snapped back, and I didn’t get my way… and a good job too, because what he did worked.”

Still, these experiences were enough to ensure that when Wilde went in to the Philips studio to cut his first long-player, Wilde About Marty, he insisted to A&R man Johnny Franz that he be backed by his own band, The Wildcats. “I put my foot down. I’d tried to have my band in from the beginning. I’d asked Johnny to let me to use my musicians on Honeycomb, but it had gone wrong, we couldn’t get the tempo or chords right. But I wouldn’t use session men on the album, they couldn’t get that feel. We were struggling to get it ourselves.”

Even so, Wilde remembers Franz, who also produced Dusty Springfield and The Walker Brothers in the same studio, with warmth. “Along with my manager Larry Parnes, he was very important in my life at that time. He was often guided by what I said, unlike some of the more dominant A&R men. He was very fair with me. He was a great musician himself, a phenomenal pianist.”

The Philips record company was barely a dozen years old in 1959, having begun by pressing and distributing other companies’ releases. Ironically, the first British No. 1 single on its distinctive blue label was Frankie Laine’s I Believe in 1953. The studio was on the ground floor of an old mansion at 2-4 Stanhope Place, near Marble Arch. While the studio regularly had 32-piece orchestras in to record, its technicians had no experience of recording rock’n’roll. The sound on Wilde recordings such as Endless Love, The Fire Of Love – another Jody Reynolds song whose original version Wilde smashed out of the park – and a superb cover of Donna, a hit for him early in 1959, were feats of excellence. “They could get great sounds and yet they were only using little four-track machines,” says Wilde.

The choice of songs on Wilde About Marty were all the singer’s, reflecting a love of American rock’n’roll, but nodding to wider tastes. Unfortunately, there is some confusion as to the personnel who played on the tracks as the Wildcats line-up was undergoing changes at this time before settling under the classic line-up of Tony Belcher on rhythm guitar, Brian ‘Licorice’ Locking on bass and Brian Bennett on drums. There’s no doubt, however, that the electric guitar solos and fills were the work of Big Jim Sullivan, who’d joined The Wildcats from Vince Eager’s band. He, along with Hank Marvin, Tony Sheridan and Joe Moretti, was one of the first rock-dedicated British axemen to emerge in the late 50s, in contrast to old-school players like Weedon, Shear and Eric Ford.

“The thing Jim had over Hank Marvin,” remembers Wilde, “was he’d do a run on the guitar so fast, his fingers would be a blur. He had that natural talent, but he didn’t have Hank’s great musical ideas. At shows, you’d get a row of girls at the front looking at me, wiggling around, while four or five guys stood watching what Jim was playing, never taking their eyes off the fretboard, just mesmerised by his fast playing. Hank never did that. He was much cooler, more Scotty Moore style… but Jim could play faster.”

Sullivan later criticised Johnny Franz for the dryness of the sound production on Wilde About Marty, and Wilde partially agrees. “Yes, Johnny did probably flatten the sound, but, again, these were early days. He was a stunning, probably classically trained musician, and this music was alien to him, I guess. But, as I say, it was this conflict that gave the British records of the time that special sound.”

The flatness of sound, characterised as the absence of echo, is evident in the opening track, which is, even so, a full-throttle take on Down The Line. It begins with a suspenseful drum roll, from the Wildcats drummer, either Bobby Woodman or Brian Bennett, some menacing rhythm guitar and Wilde’s fiery vocal coming in over the top. Other outright rockers on the album, Put Me Down, Mean Woman Blues and High School Confidential followed the similar formula as head arrangements of raw, visceral excitement, not unlike the rockabilly revivalists in the late 70s. Although Wilde’s vocals obviously drew on Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis, as he says, “You can’t help something of yourself coming through on a recording.”

Never a screamer, he had his own style, midway between Elvis’s earthiness, and Billy Fury’s yearning and The Everly Brothers’ purity, and the album had a fine version of the latter’s Love Of My Life. The Wilde singing persona also came across on Dream Lover. “That was a song I liked, but I sang it my way. I had my own tone and it came across on that. I sung it in a lower key to Bobby Darin, which suited the timbre of my voice.”

The one outright rockabilly number Blue Moon Of Kentucky stuck close to Presley’s Sun reworking, but as The Wildcats had an electric bass, rim shots on the snare drum, Bill Haley-style, replicated the click of slap bass. More interesting was the take on Arthur ‘Big Boy’ Crudup’s So Glad You’re Mine, again familiar to Wilde thanks to Presley’s version, but which sat well with his love for the blues. Like Elvis, he recorded it as a shuffle, but ditched the barrelhouse piano for a kettledrum, and stamped his own vocal signature on it by dropping his voice and drawing out the words on the punchline. Some stinging breaks from Sullivan rounded off an excellent recording. “The lines are funny,” argues Wilde. “What does ‘she’s like a cannonball’ mean? But it’s effective. I loved Elvis’s work but it had that kind of Frankie Laine impact where it reaches out and hits you on the nose!”

All American Boy was a talking blues by American country singer Bobby Bare, sending up Presley’s US Army draft. Wilde, who accompanied himself on acoustic guitar on the recording, performed it live on Oh Boy! and at the Royal Variety Performance before the Queen Mother, his easy swagger reflective of a man who has acquitted himself well on stage and screen. On some of the tracks, Ivor Raymonde was brought as arranger. Raymonde went to his grave in 1990 still with questions to answer for Gene Vincent’s all-time worst recording, the appalling Humpity Dumpity, recorded with his orchestra in London in 1963, but on the plus side he did fine work with such artists as Billy Fury on Halfway To Paradise, and he was effective enough on Wilde About Marty. One for the squares, but well done all the same, was the ballad Are You Sincere?, a hit for Andy Williams, on which probably Johnny Franz contributed some upmarket, nightclub-style tinkling on the ivories.

For all his affability, Wilde is not easily satisfied, and says this debut album, a steady rather than a big seller, left him with no great sense of pride. “I would have wanted it to be better. I aimed as high as I could, and it felt like pushing a train up a hill. You could never get exactly what you wanted and you were educating musicians and sound men all the time.”

Whatever its shortcomings, Wilde About Marty is a historic album as well as a classic one. In 1959, rock’n’roll LPs by British artists were rare. Tommy Steele’s Stage Show and Cliff Richard And The Drifters’ Cliff, had both been recorded live. Steele’s The Tommy Steele Story (1957) was, the odd highlight excepted, milk-and-water stuff. Wilde About Marty was a proper rockin’ album, and also marked the real entry of the first generation of British rockers into the technical environs of the recording studio and the process of production. Marty Wilde was a pioneer, and every single rock album that has since been produced in the UK ever since is the spiritual descendent of Wilde About Marty.

Jack Watkins